1 Meet WebAssembly

Modern web experiences live and die by performance, yet browsers historically ran only JavaScript, which is being pushed to do ever heavier work. In 2017, all major browsers shipped support for WebAssembly (Wasm), a compact, low-level, assembly-like format that executes at near‑native speed. Designed as a compilation target, WebAssembly lets code written in languages such as C, C++, and Rust run on the web, enabling reuse of existing codebases, powering new high-performance libraries, and opening a path to run beyond the browser as well.

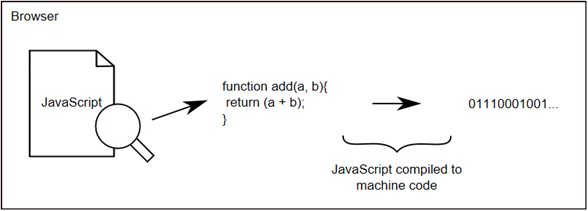

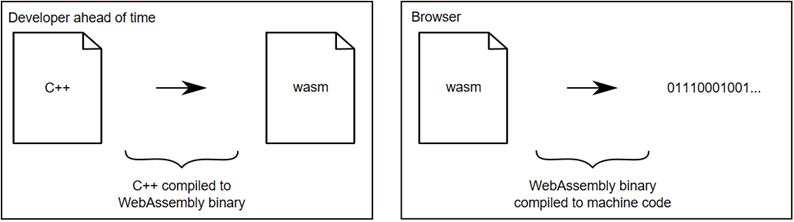

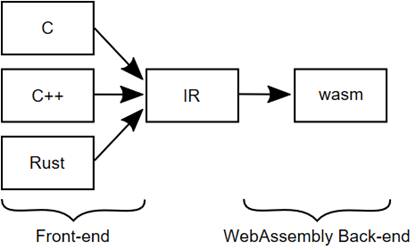

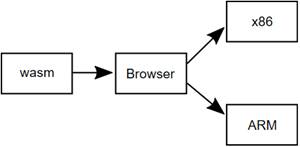

WebAssembly addresses performance from download to execution. Whereas JavaScript is interpreted and JIT-compiled around dynamic types, Wasm is statically typed and compiled ahead of time to a binary bytecode that is fast to transmit, validate, and compile—benefiting startup on the very first run and further boosted by streaming compilation. It improves on asm.js (a typed subset of JavaScript) by avoiding large, parse-heavy JS files and by being a true compiler target. The workflow compiles source to an intermediate representation and then to .wasm bytecode; the browser validates it in a single pass and compiles it to machine code before instantiating the module. Modules expose a small set of numeric value types, manage their own linear memory, include well-defined known sections plus flexible custom sections, and also have a human-readable text form based on s-expressions for tooling and debugging.

Security comes from running inside the hardened, sandboxed JavaScript VM and adhering to the same policies (such as same-origin). Modules receive bounded linear memory, access function tables indirectly, and cannot touch the execution stack directly, limiting attack surface. WebAssembly complements rather than replaces JavaScript: today modules interoperate with JS (which can call Web APIs on their behalf), with direct host bindings planned. While C/C++ and Rust are first-class, many other languages are experimenting with Wasm targets. Support spans all major desktop and many mobile browsers, as well as Node.js, making it practical to accelerate performance-critical parts of applications, reuse existing native code, and deliver faster, more responsive web experiences.

JavaScript compiled to machine code as it executes

C++ being turned into WebAssembly and then into machine code in the browser

Compiler front-end and back-end diagram

Compiler front-end with a WebAssembly back-end diagram

Wasm file loaded into a browser and then compiled to machine code diagram

Summary

As you saw in this chapter, WebAssembly brings a number of improvements with many being around performance as well as language choice and code reuse. Some of the key improvements that WebAssembly brings are the following:

- Faster transmission and download times because of the smaller file sizes due to the use of a binary encoding.

- Due to the way the files are structured, they can be parsed and validated quickly. Also because of how they’re structured, portions of the file can be compiled in parallel.

- With streaming compilation, WebAssembly modules can be compiled as they’re being downloaded so that they’re ready to be instantiated the moment the download completes speeding up load time considerably.

- Faster code execution for things like computations due to the use of machine level calls rather than the more expensive JavaScript engine calls.

- Code doesn’t need to be monitored before it’s compiled to determine how it’s going to behave. The result is that code runs at the same speed every time it runs.

- Being separate from JavaScript, improvements can be made to WebAssembly faster because it won’t impact the JavaScript language.

- The ability to use code written in a language, other than JavaScript, in a browser.

- Increased opportunity for code reuse by structuring the WebAssembly framework in such a way that it can be used in the browser and outside of the browser.

WebAssembly in Action ebook for free

WebAssembly in Action ebook for free