1 Making programs safer

This chapter argues that programming is far riskier than it appears, citing the high cost of software defects and the increasing stakes as software makes real-world decisions. Its central message is to make programs safer by embracing simplicity and discipline: acknowledge human limits, prefer designs that reduce places where bugs can hide, and adopt functional ideas such as immutability, referential transparency, and clear separation of concerns.

The text highlights common traps—mutable state, ad-hoc control flow, nulls, exceptions used as control, and unrestrained I/O—and shows how to corral them. Safer code is built from pure functions that depend only on their inputs and return values without side effects. Such referentially transparent code is deterministic, self-contained, easier to reason about and test (often without mocks), more modular and composable, and inherently safer in concurrent contexts because it avoids shared mutable state. Effects remain necessary, but the guidance is to isolate them at the boundaries so the core stays pure and predictable.

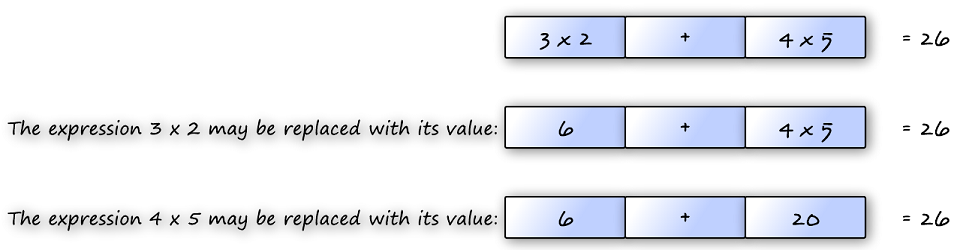

To reason about programs, the chapter introduces the substitution model: any pure expression can be replaced by its value without changing behavior. A concrete example refactors a purchase operation from “do-and-return” into “describe-and-return,” returning both the domain value and a representation of the effect (for instance, a payment to be processed later or combined). This leads naturally to abstraction and higher-order utilities—grouping, mapping, reducing, and eventually folding—that promote reuse and correctness by implementing fragile logic once. The result is Kotlin code that is simpler to test, compose, and evolve, with effects clearly managed at the edges.

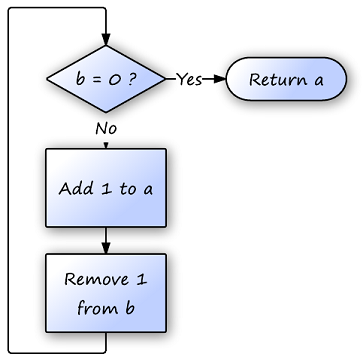

Figure 1.1. A flow chart representing a program as a process that occurs in time. Various things are transformed and states are mutated until the result is obtained.

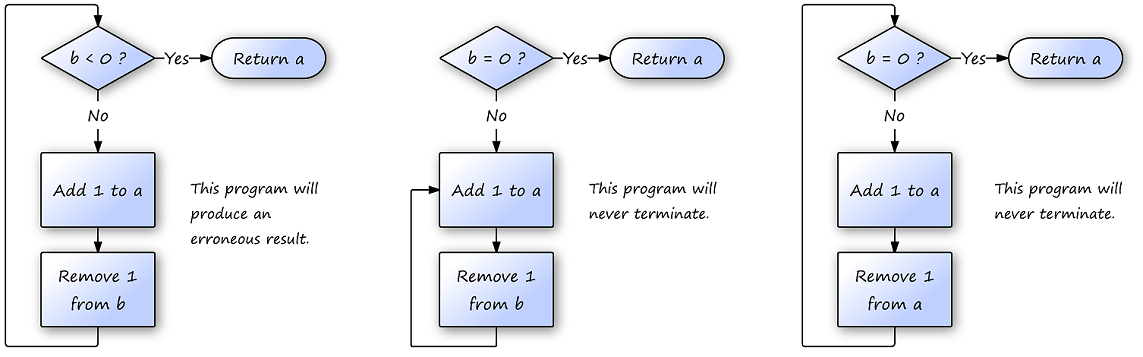

Figure 1.2. Three buggy versions of the same program

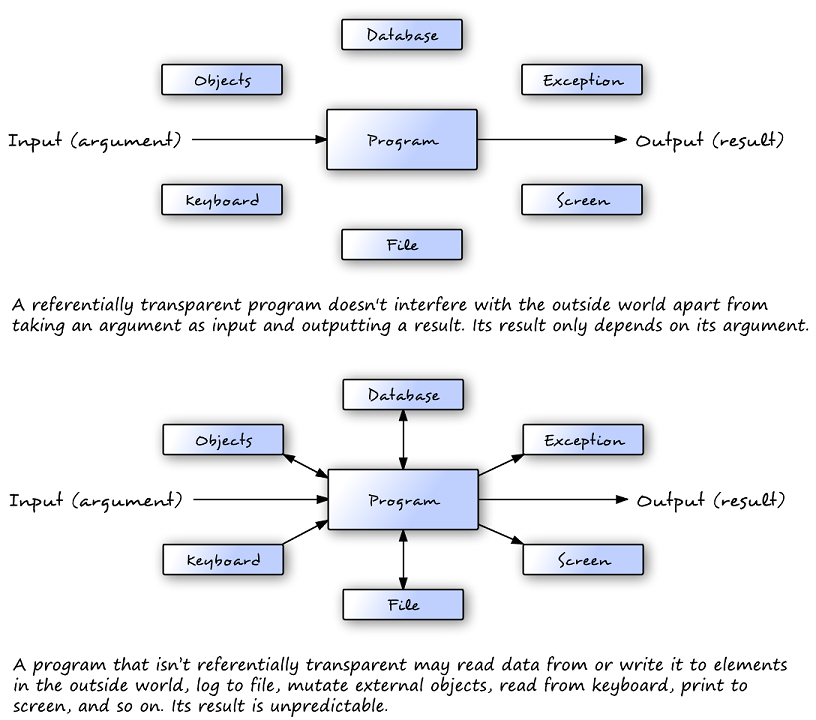

Figure 1.3. Comparing a program that’s referentially transparent to one that’s not

Figure 1.4. Replacing referentially transparent expressions with their values doesn’t change the overall meaning.

Summary

- You can make programs safer by clearly separating functions, which return values, from effects, which interact with the outside world.

- Functions are easier to reason about and easier to test because their outcome is deterministic and doesn’t depend on an external state.

- Pushing abstraction to a higher level improves safety, maintainability, testability, and reusability.

- Applying safe principles like immutability and referential transparency protects programs against accidental sharing of a mutable state, which is a huge source of bugs in multithreaded environments.

FAQ

Why does the chapter call programming “dangerous”?

Because software defects can have severe real‑world consequences. The chapter cites historic failures (for example, the Y2K date bug and the Ariane 5 overflow) to show how small mistakes can become extremely costly. Safer programming reduces the likelihood and scope of such failures.

What are “effects” and “side effects,” and why are they risky?

Effects are interactions with the outside world (I/O, database/file/network access, or mutating any state outside a function’s scope). A side effect is an observable effect in addition to a returned value. Side effects make code harder to reason about, test, and compose, and they can introduce nondeterminism and hidden dependencies.

What is referential transparency, in practical terms?

Code is referentially transparent if its output depends only on its inputs and it neither observes nor mutates external state. Such code is self‑contained, deterministic, does not (by design) throw recoverable exceptions, and doesn’t rely on external devices. You can replace a call with its value without changing program behavior.

How does the substitution model help me reason about programs?

If a function is pure, you can replace the call with its returned value anywhere it appears without changing meaning. This makes reasoning, refactoring, and proof of correctness far easier. If a function performs logging or other effects, this equivalence breaks, and substitution changes behavior.

How can I handle effects safely if most programs must do I/O?

Separate effect evaluation from pure logic. Return a description of the effect along with the computed value, then evaluate those effects at the program’s edges. The donut example returns both a Donut and a Payment (a representation of the charge), deferring the actual bank interaction.

What concrete practices reduce bugs according to the chapter?

- Avoid mutable references; if mutation is unavoidable, abstract it behind a dedicated component.

- Avoid raw control structures (loops/branching) in favor of higher‑level operations.

- Restrict effects to well‑defined boundaries in the codebase.

- Avoid throwing exceptions for control flow; model failures explicitly instead.

Why does side‑effect‑free code improve testing?

Pure functions are deterministic and self‑contained, so you don’t need mocks or complex test scaffolding to isolate external dependencies. Tests become simple input‑to‑output checks, which are faster and more reliable.

How does the donut example illustrate safer design?

The unsafe version charges the card as a side effect. The safer version returns Purchase(donut, payment), separating decision (what to charge) from execution (when/how to charge). This enables batching (e.g., group payments by card and combine with groupBy + reduce) and simplifies testing.

What’s the difference between reduce and fold, and when should I use each?

reduce combines list elements using an operation and requires a non‑empty list; its result type matches the element type. fold starts from an explicit initial value, works on empty lists, and can produce a result of a different type. Use fold when you need an initial accumulator or a different result type.

How does abstraction make programs safer and more reusable?

By extracting common structure (e.g., list traversals) into generic operations like map, reduce, and fold, you write complex, error‑prone logic once and reuse it everywhere. This minimizes duplication, shrinks the surface area for bugs, and enables easy recomposition and even transparent switches (e.g., from serial to parallel processing later on).

The Joy of Kotlin ebook for free

The Joy of Kotlin ebook for free