1 The Drug Discovery Process

Drug discovery is presented as a long, costly, and failure-prone endeavor, where moving a therapeutic idea to market takes many years, billions of dollars, and faces steep attrition. The chapter argues that artificial intelligence—particularly machine learning and deep learning—offers leverage against the twin challenges of vast chemical and biological search spaces by accelerating prediction, prioritization, and design. It sets a shared foundation in terminology, data representation, and workflows so readers can see where computational methods best fit within discovery and how they complement experimental efforts and regulatory realities.

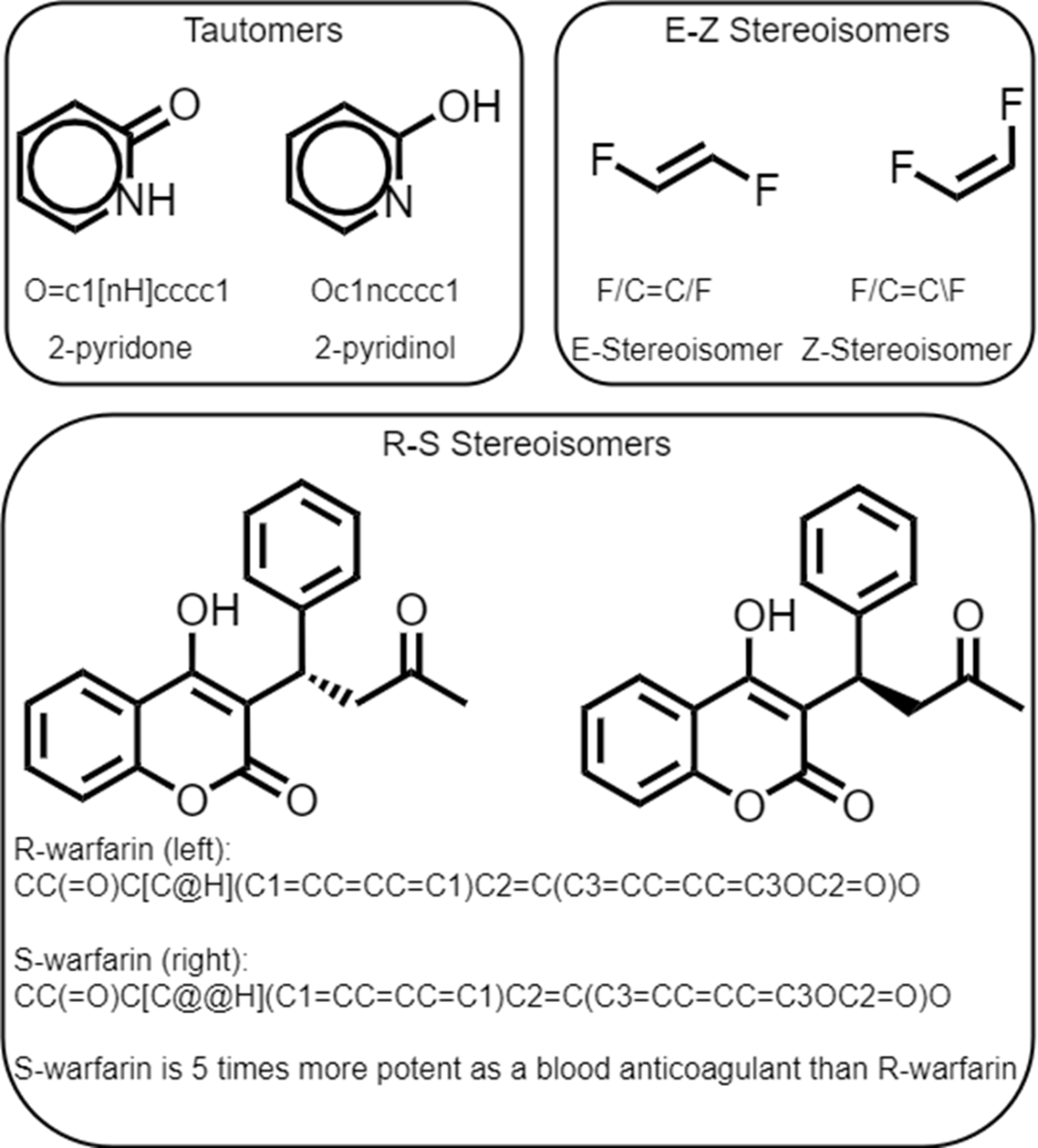

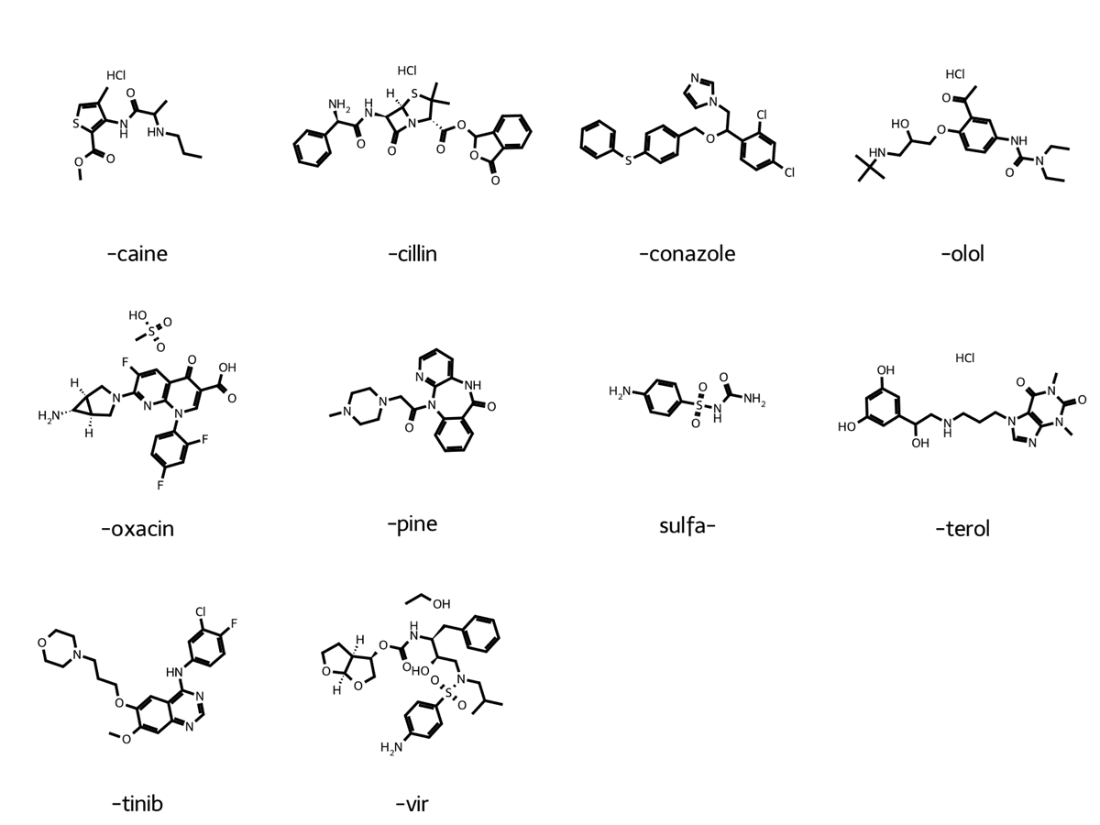

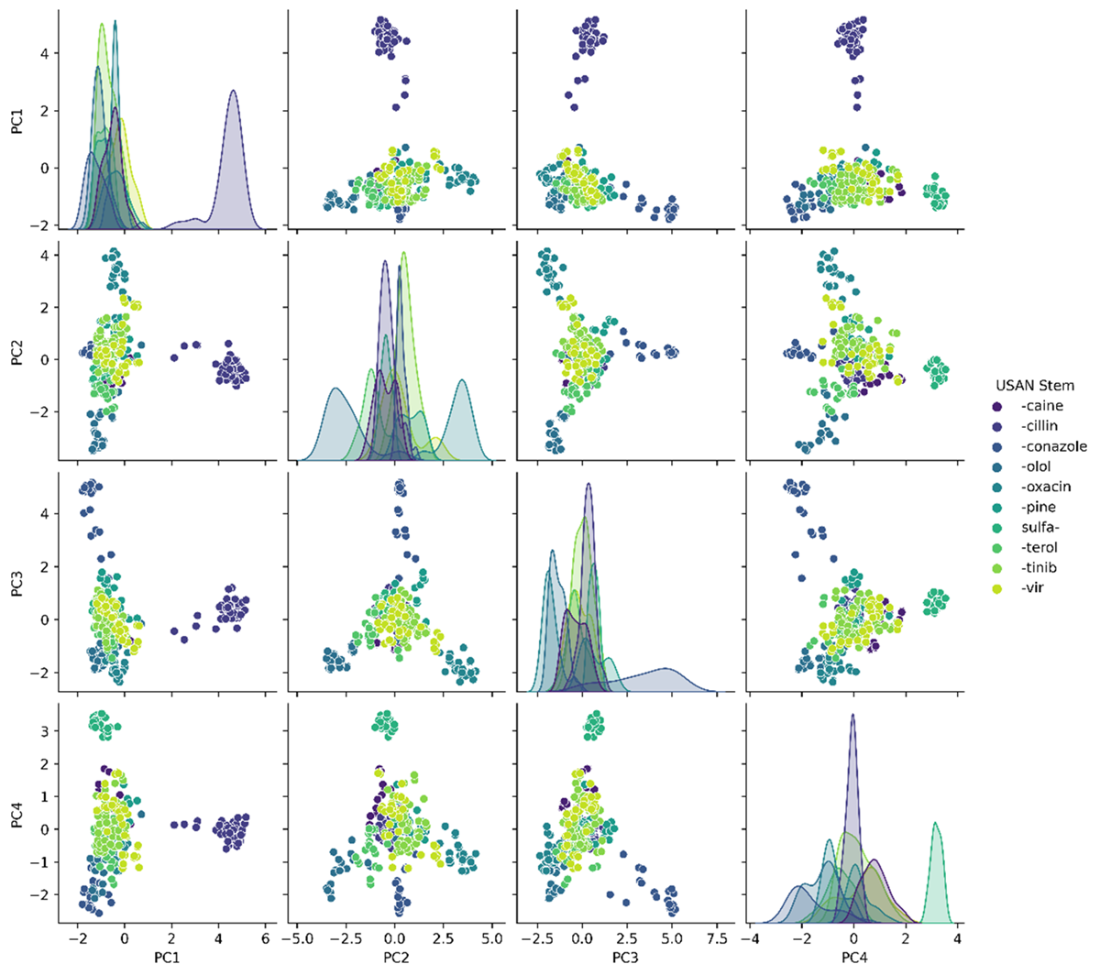

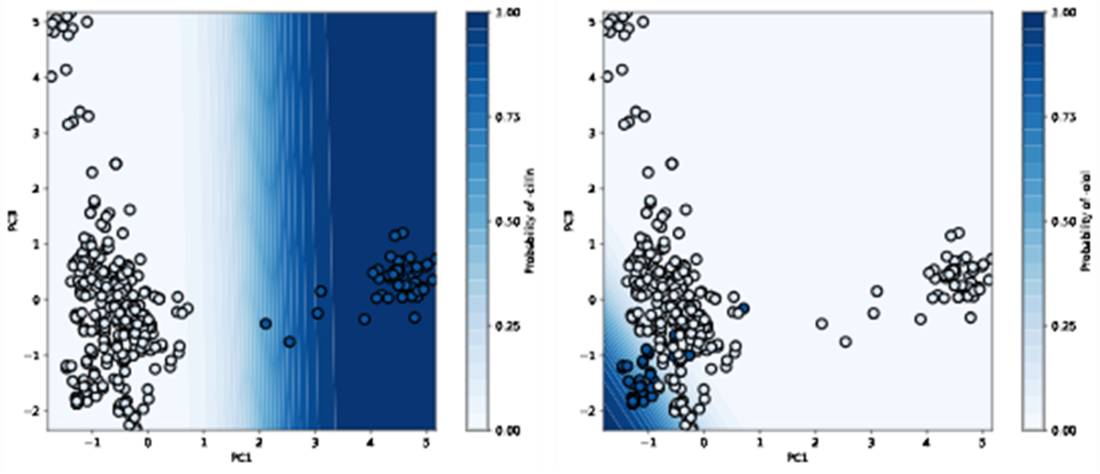

The chapter surveys high-impact AI applications already reshaping discovery: virtual screening and molecular property prediction that triage enormous libraries far faster than physics-based simulations; generative chemistry that inverts the search by proposing novel structures to meet desired property profiles; reaction prediction and retrosynthesis that plan feasible syntheses for new candidates; and protein-structure prediction that closes the gap between abundant sequences and scarce 3D structures. It underscores why deep learning’s learned representations reduce human bias versus hand-crafted features, enabling novelty beyond “me-too” optimization while acknowledging privileged scaffolds, safety liabilities, and patentability constraints. To make these ideas concrete, it introduces molecular representations (SMILES, canonical and isomeric variants, stereochemistry), core ML concepts (supervised/unsupervised learning, generalization), and practical tooling (RDKit), illustrated with simple dimensionality reduction and classification over approved drugs grouped by USAN stems.

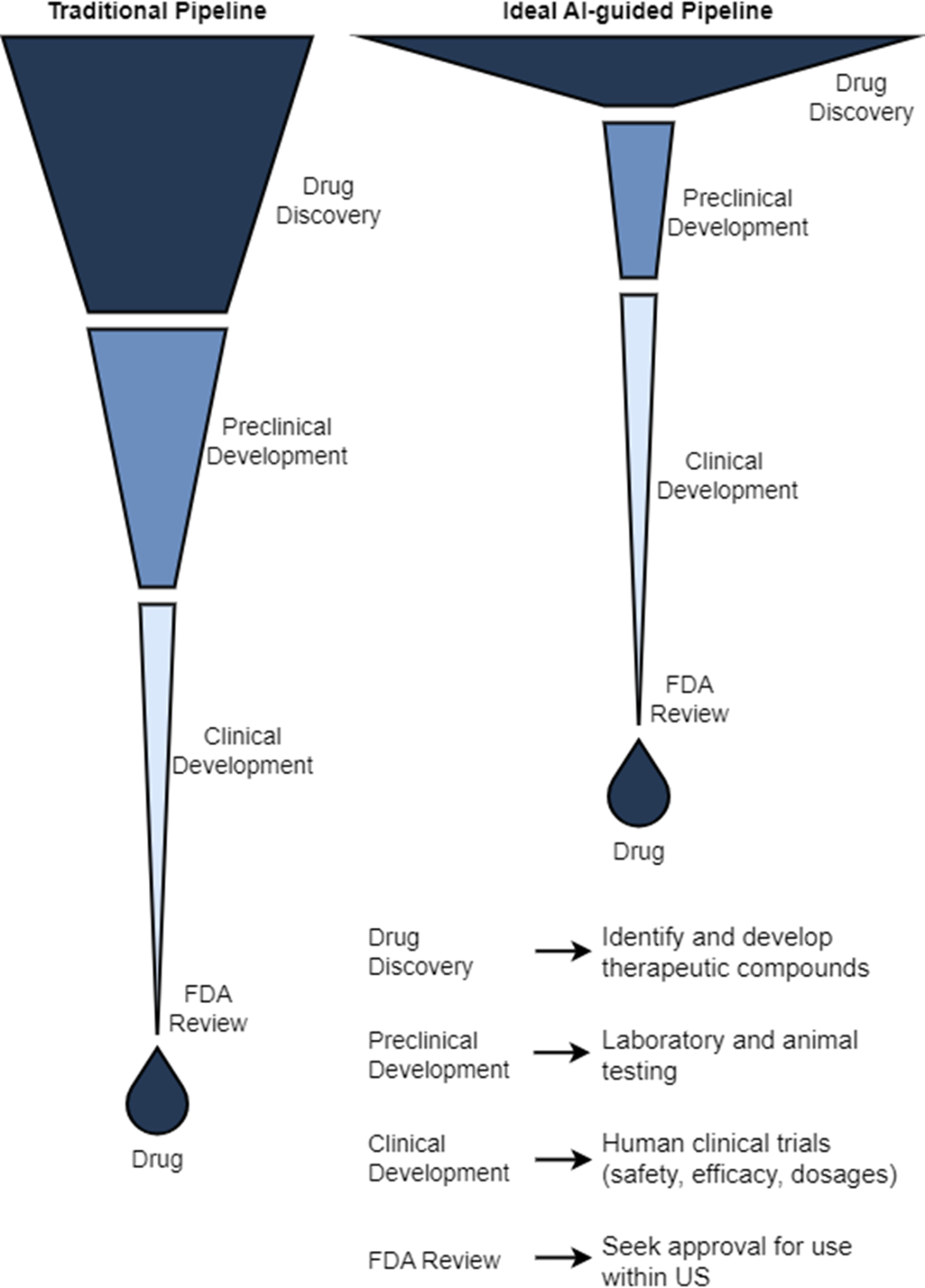

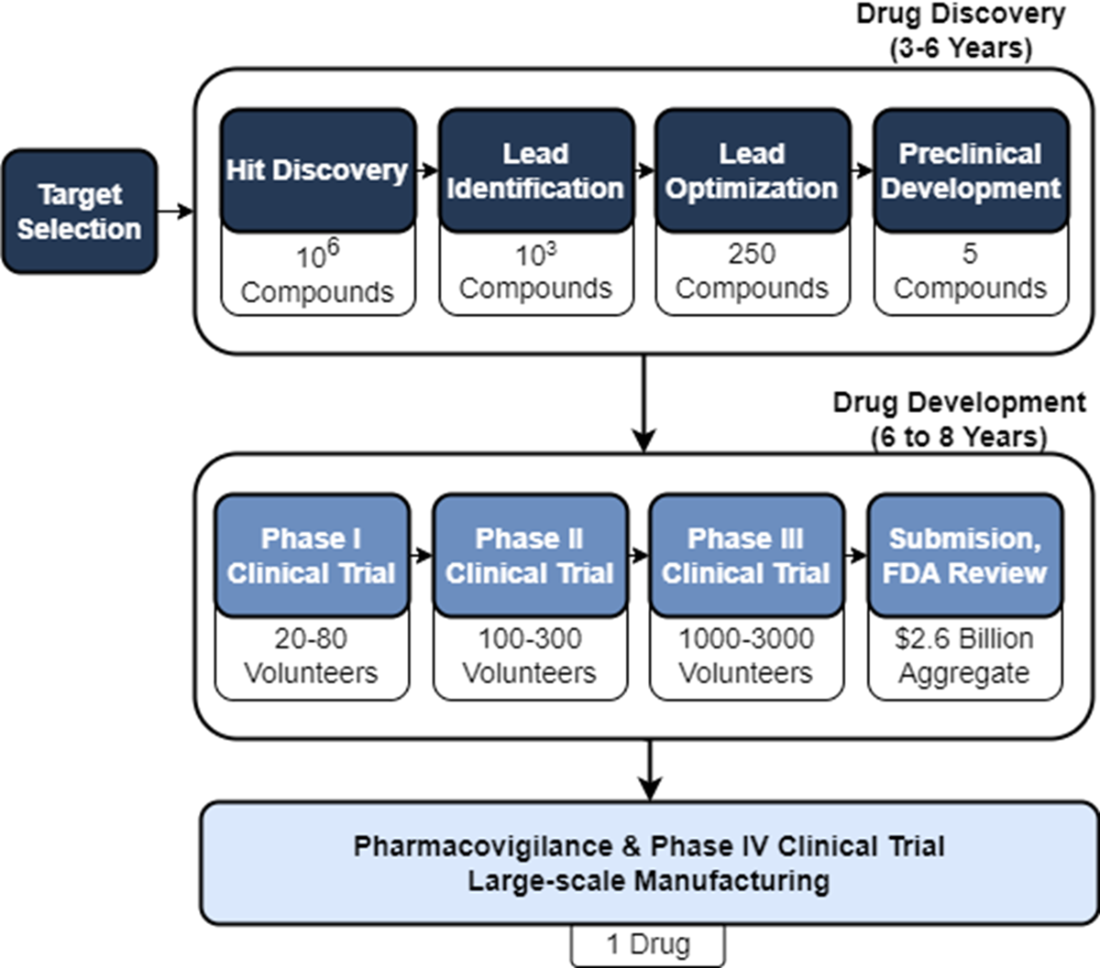

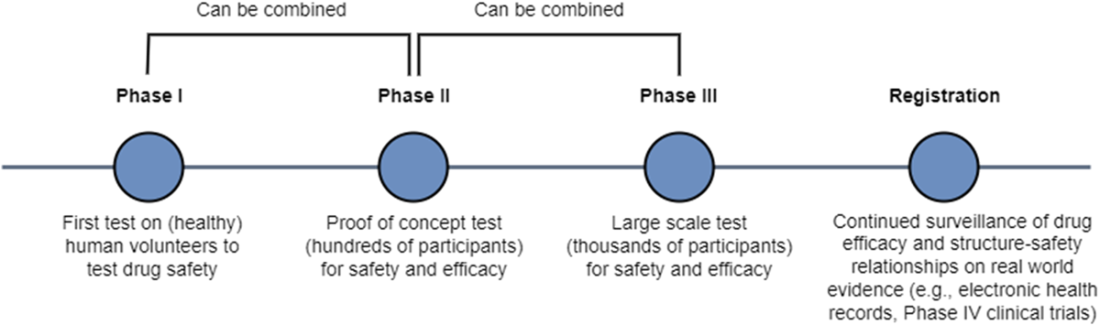

With that groundwork, the chapter maps the discovery-to-development pipeline: choosing and validating a disease-relevant target; identifying hits via computational or high-throughput screens; refining to leads and optimizing potency, selectivity, and ADMET profiles; and advancing optimized candidates through preclinical testing. It contrasts pharmacokinetics (what the body does to the drug) with pharmacodynamics (what the drug does to the body), then outlines clinical Phases I–III with escalating scale and evidence demands, along with expedited pathways for urgent or first-in-class therapies. Across these stages, AI’s role is to broaden the candidate funnel, spot failures earlier, guide design and synthesis, and ultimately reduce risk, time, and cost on the path to safer, more effective medicines.

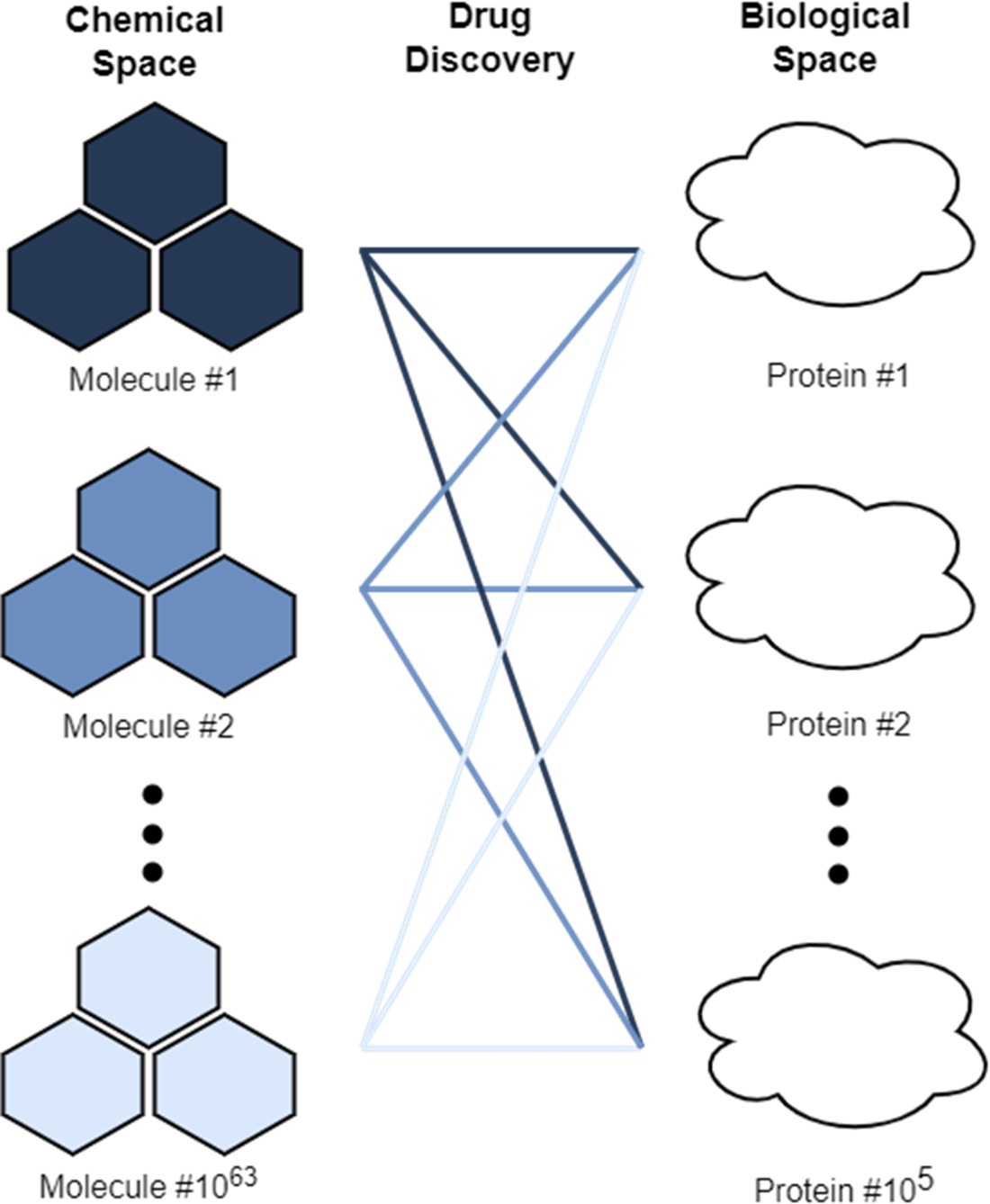

Drug discovery can be thought of as a difficult search problem that exists at the intersection of the chemical search space of 1063 drug-like compounds and the biological search space of 105 targets.

Using AI to guide early prediction and optimization of drug-like molecules, we can broaden the number of considered candidate molecules, identify failures earlier when they are relatively inexpensive, and accelerate delivery of novel therapeutics to the clinic for patient benefit.

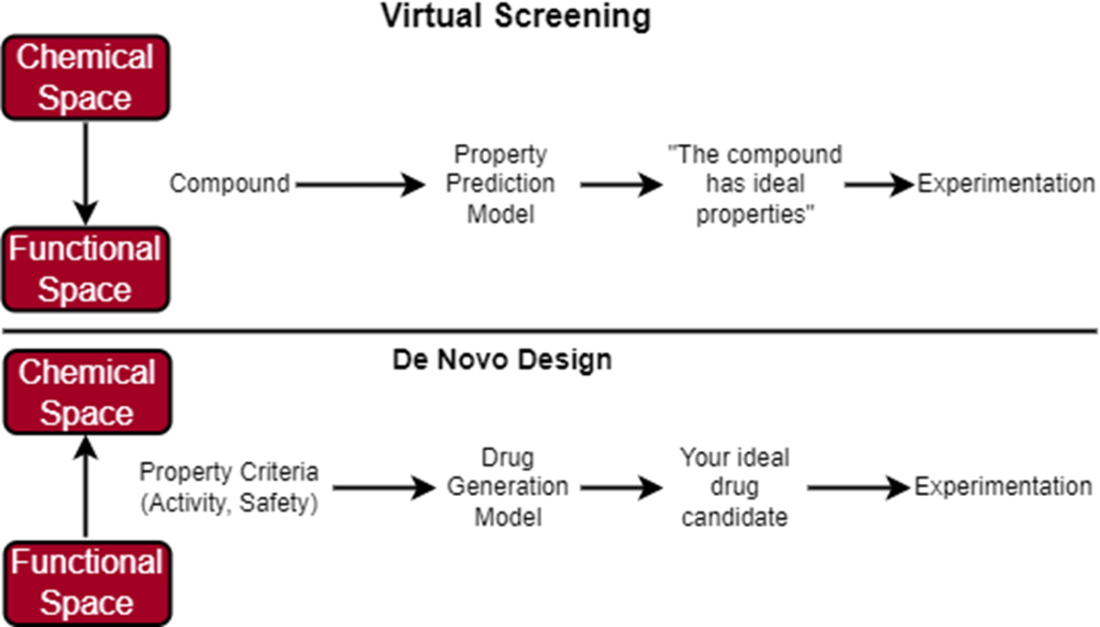

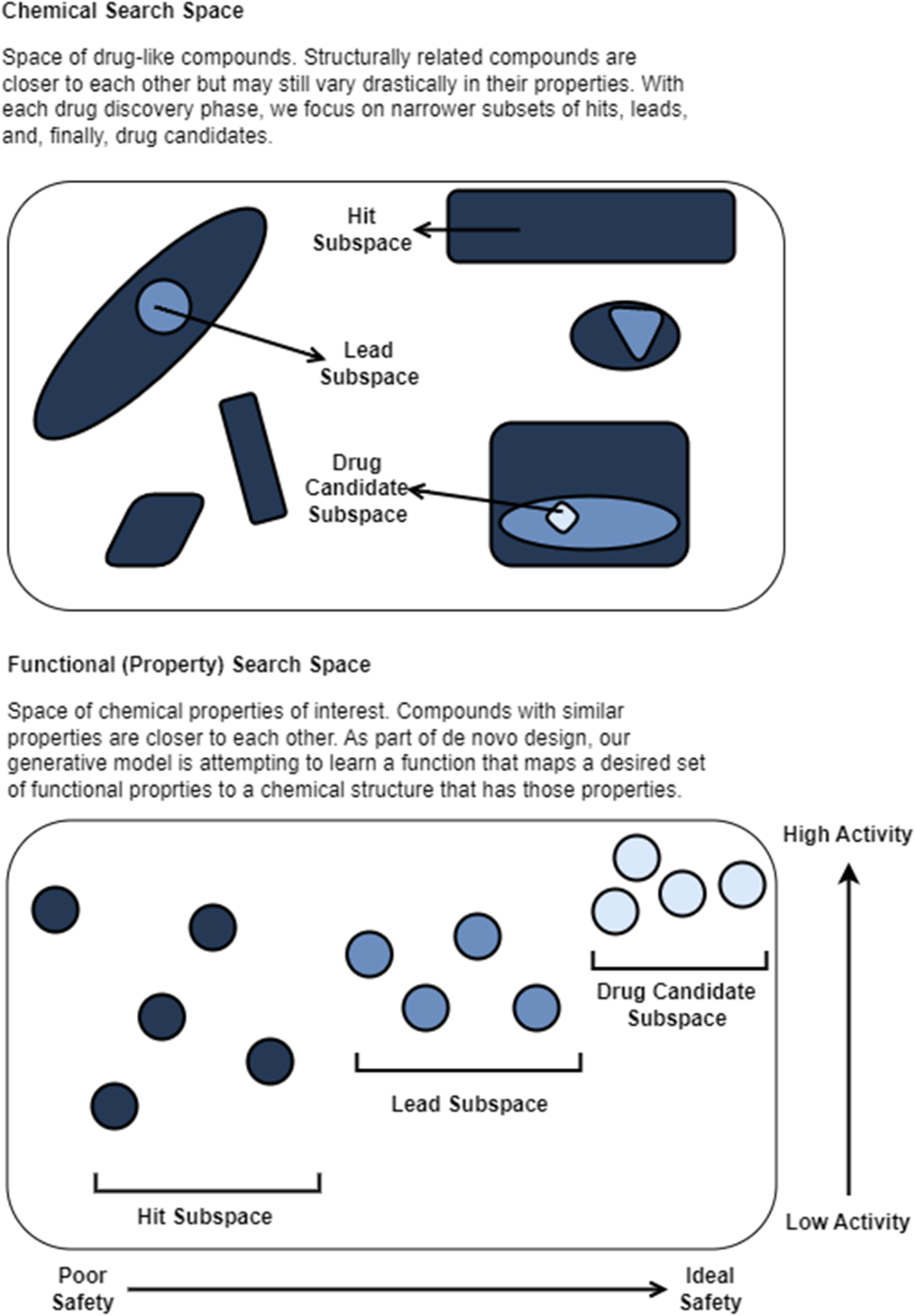

In virtual screening, we start with a large, diverse library of compounds that we can filter using a predictive model that has learned to predict what properties each compound has. Our predictive model has learned how to map the chemical space to the functional space. If the compound is predicted to have optimal properties, we carry it over for further experiments. In de novo design, we start with a defined set of property criteria that we can use along with a generative model to generate the structure of our ideal drug candidate. Our generative model knows how to map the functional space to the chemical space.

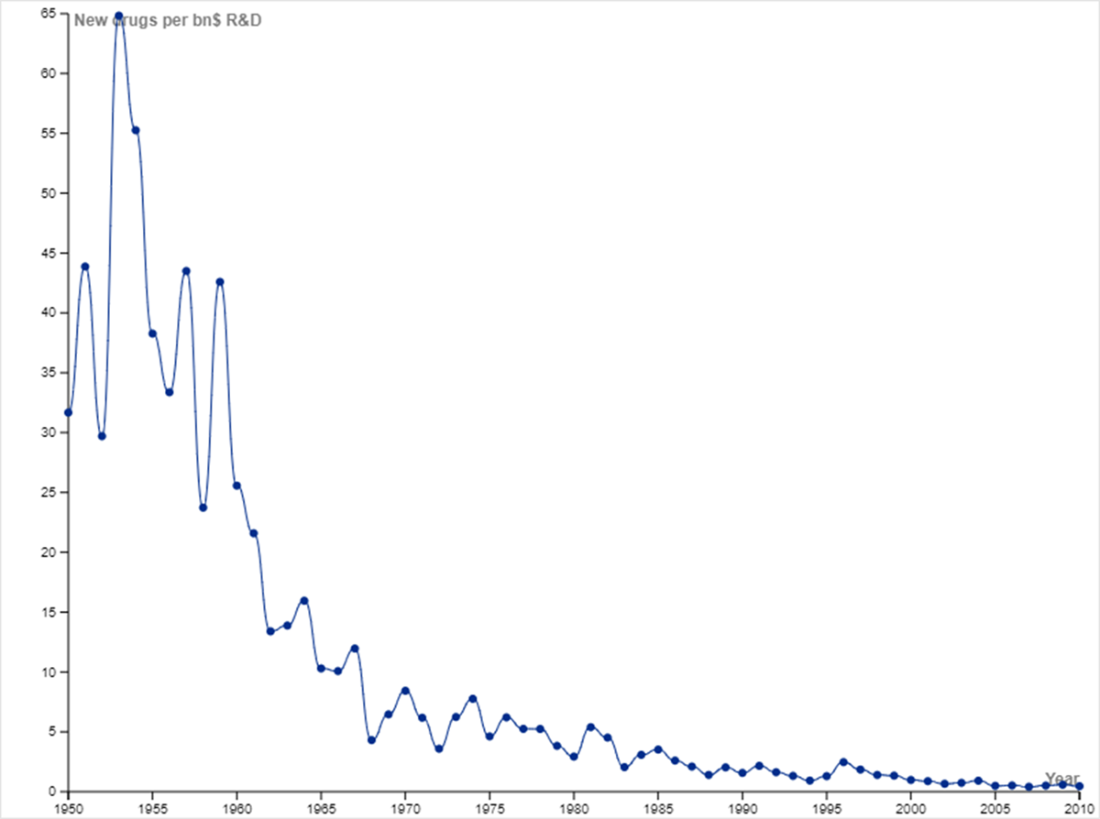

New drugs per billion USD of R&D reflects a downward trajectory. You may have heard of Moore’s Law, which is the observation that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years. Moore’s Law implies that computing power doubles every couple of years while cost decreases. Eroom’s Law (Moore spelled backwards) is the observation that the inflation-adjusted R&D cost of developing new drugs doubles roughly every nine years. Eroom’s Law reflects diminishing returns in developing new drugs, including factors such as lower risk tolerance by regulatory agencies (the “cautious regulator” problem), the “throw money at it” tendency, and need to show more than a modest incremental benefit over current successful drugs (the “better than the Beatles” problem). The plot was constructed with data from Scannell et al., which discusses the trend in greater detail [6].

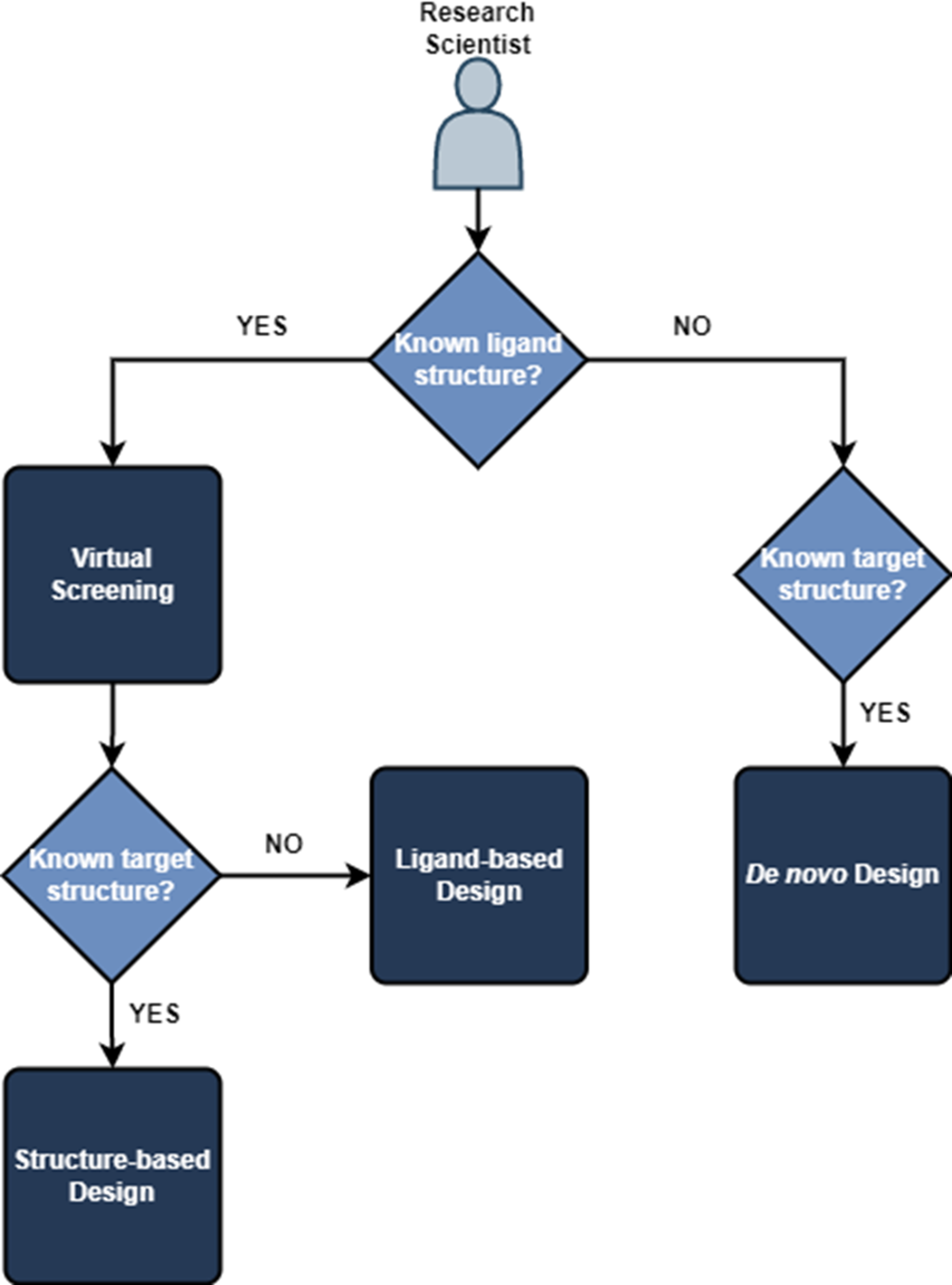

If we know both the structure of our ligand or compound and the target, we can use structured-based design methods. If we only know the ligand structure, we are restricted to ligand-based design methods. Alternatively, if we only know the target structure, we can use de novo design to guide generation of a suitable drug candidate.

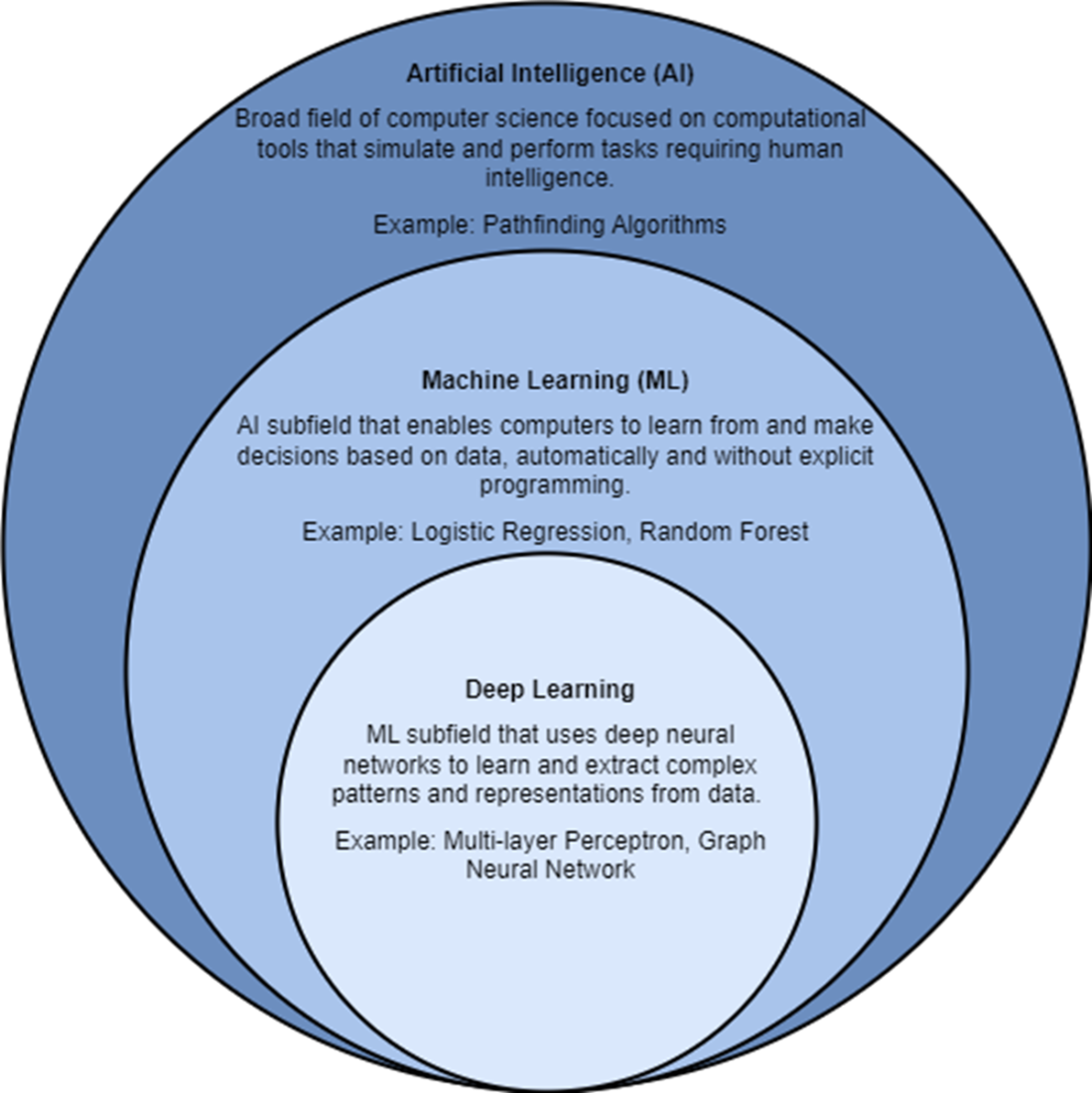

Artificial intelligence, ML, and deep learning are all related to each other.

Example pairs of isomeric SMILES.

Example drug molecules for each USAN stem classification within our data set.

Chemical space exploration in a reduced, 4-dimensional space.

Decision boundary of our logistic regressor for classifying “-cillin” (left) and “-olol” (right) USAN stems. For each plot, colored samples belong to the positive class and uncolored samples belong to the negative class.

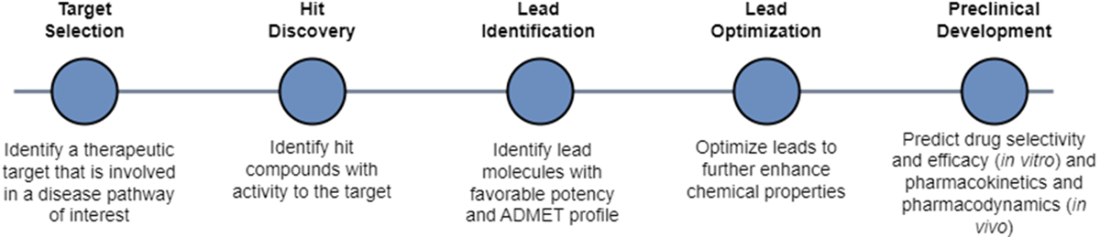

We can breakdown drug design into target identification and validation, hit discovery, hit-to-lead (lead identification), lead optimization, and preclinical development. Once a drug candidate has progressed to the drug development stage, it will need to pass multiple phases of clinical trials testing safety and efficacy prior to submission to and review by the FDA and launch to market.

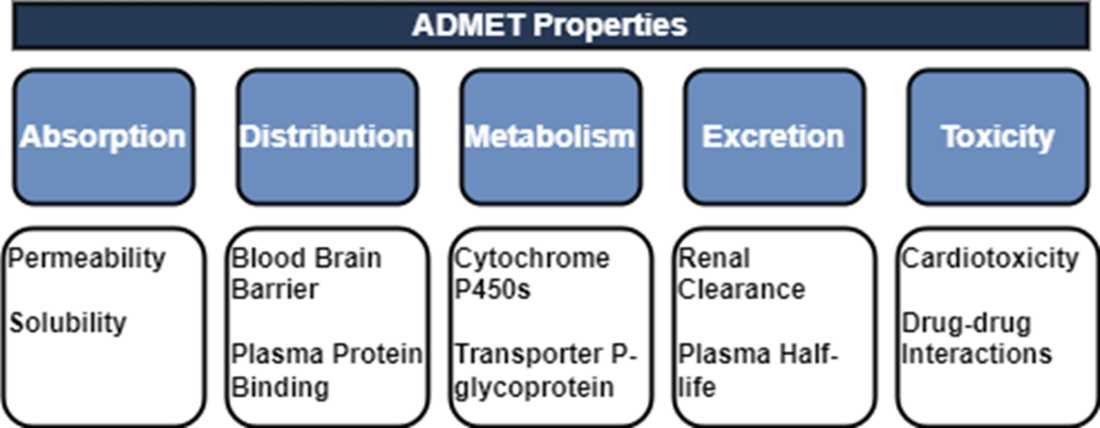

We can break down the ADMET properties into the following broad descriptions. Absorption refers to the process by which a drug enters the bloodstream from its administration site, such as the gastrointestinal tract for oral drugs or the respiratory system for inhalation drugs. Distribution pertains to the movement of a drug within the body once it has entered the bloodstream. Metabolism refers to the biochemical transformation of a drug within the body, primarily carried out by enzymes. Metabolic processes aim to convert drugs into more polar and water-soluble metabolites, facilitating their elimination from the body. Excretion involves the removal of drugs and their metabolites from the body. Toxicity assessment aims to evaluate the potential adverse effects of a drug candidate on various organs, tissues, or systems.

We can segment the early drug discovery pipeline into four main phases: target identification, hit discovery, hit-to-lead or lead identification, and lead optimization. Target identification designates a valid target whose activity is worth modulating to address some disease or disorder. Hit discovery uncovers chemical compounds with activity against the target. Lead identification selects the most promising hits and lead optimization improves their potency, selectivity, and ADMET properties to be suitable for preclinical study.

In virtual screening, we conducted our search across a chemical space consisting of an enormous set of molecules. In de novo design, we are still conducting an (informal) search, just not across the chemical space. We are now searching across the functional space of potential molecular properties. If our model “learns” which section of the functional space maps to molecules that have ideal binding affinity and safety, then perhaps it can reverse-engineer novel molecule structures in the chemical space that match our functional criteria.

Preclinical trials evaluate drug candidate safety and efficacy on model organisms. Phase I clinical trials evaluate drug candidate safety in its first exposure to humans. Phase II and Phase III clinical trials continue to collect data on safety while measuring drug candidate efficacy on larger groups of patients. The pass rate of our lead compounds decreases drastically as they progress beyond preclinical stages, along with an increase in the associated time to test them.

Summary

- Developing therapeutics entails a long, arduous process. Traditional development from ideation to market is costly (magnitude of billions of dollars), lengthy (10 to 15 years), and risky (attrition of over 90%). Through advances in AI, we can discover cures that have better safety profiles, address medical conditions or diseases with low coverage, and can reach patients quicker.

- Drug discovery can be thought of as a difficult search problem that exists at the intersection of the chemical search space of 1063 medicinal compounds and the biological search space of 105 targets.

- Applications of AI to drug design include molecule property prediction for virtual screening, creation of compound libraries with de novo molecule generation, synthesis pathway prediction, and protein folding simulation.

- ML is a subfield of AI that enables computers to learn from and make decisions based on data, automatically and without explicit programming or rules on how to behave. Example ML algorithms include logistic regression and random forests. Deep learning is a subfield of ML that uses deep neural networks to extract complex patterns and representations from data.

- We can segment the early drug discovery pipeline into four main phases: target identification, hit discovery, hit-to-lead or lead identification, and lead optimization. Target identification designates a valid target whose activity is worth modulating to address some disease or disorder. Hit discovery uncovers chemical compounds with activity against the target. Lead identification selects the most promising hits and lead optimization improves their potency, selectivity, and ADMET properties to be suitable for preclinical study.

- Popular, well-maintained chemical data repositories include ChEMBL, ChEBI, PubChem, Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFoldDB, and ZINC. When using a new data source, learn how it was assembled and how quality is maintained. Garbage data in, garbage model out. See “Appendix B: Chemical Data Repositories” for more information.

Machine Learning for Drug Discovery ebook for free

Machine Learning for Drug Discovery ebook for free