1 Introduction

This chapter lays the foundation for building low‑latency applications by defining latency as the time between a cause and its observed effect and explaining why that framing matters across the stack. It motivates a systematic, practice‑oriented approach—combining concrete techniques, tools, and mental models—so developers can diagnose and reduce delays rather than rely on scattered folklore. The discussion also situates latency within physical limits (such as the speed of light), clarifies its relationship to other performance metrics, and sets expectations for how the rest of the book balances theory with practical guidance.

Latency is measured in time units and appears at every layer, from CPU caches and memory to disks, networks, operating systems, and application code. The chapter uses everyday and software examples—like light switches, HTTP requests, and Linux packet processing—to show how end‑to‑end delay compounds across components, varies between runs, and directly shapes user‑perceived responsiveness. It also contrasts common terminology (latency, response time, service time, wait time) and stresses that getting intuition for microsecond and nanosecond scales is key when chasing the last mile of performance.

The importance of low latency spans three themes: improving user experience (with clear business impact), meeting real‑time constraints (hard vs. soft deadlines), and boosting efficiency now that “free” hardware speedups have plateaued. The chapter distinguishes latency from bandwidth and throughput, highlights when designs trade latency for throughput (for example, via pipelining and concurrency), and notes the principle that bandwidth is easier to add than lower latency. Finally, it introduces the latency–energy tension—techniques like busy polling can cut delay yet raise power use—and shows how workload patterns determine whether you can optimize for both.

60 ms Length of a nanosecond. Source: https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_692464

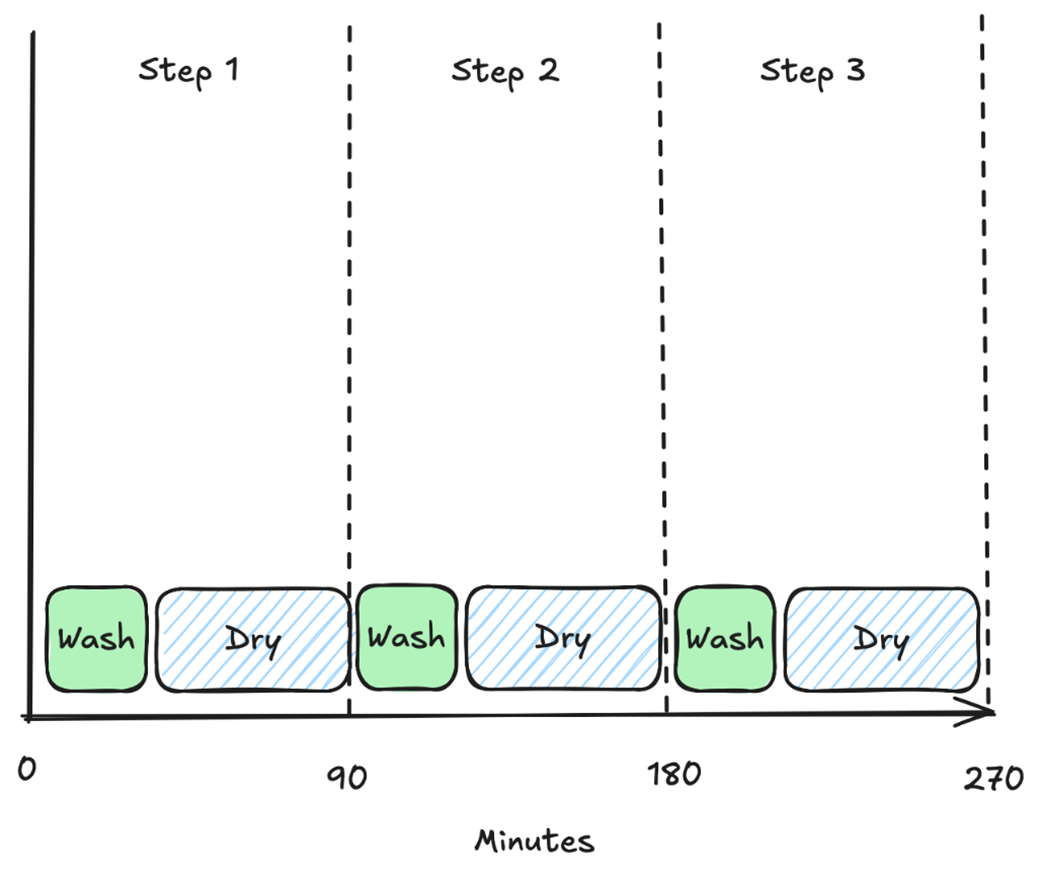

Processing without pipelining. We first perform step W (washing) fully and only then perform step D (drying). As the time to complete W is 30 minutes and the time to complete D is 60 minutes, each step takes 90 minutes in total. Therefore, we say that the latency to wash and dry clothes is 90 minutes and the throughput is 1/90 loads of laundry washed per minute.

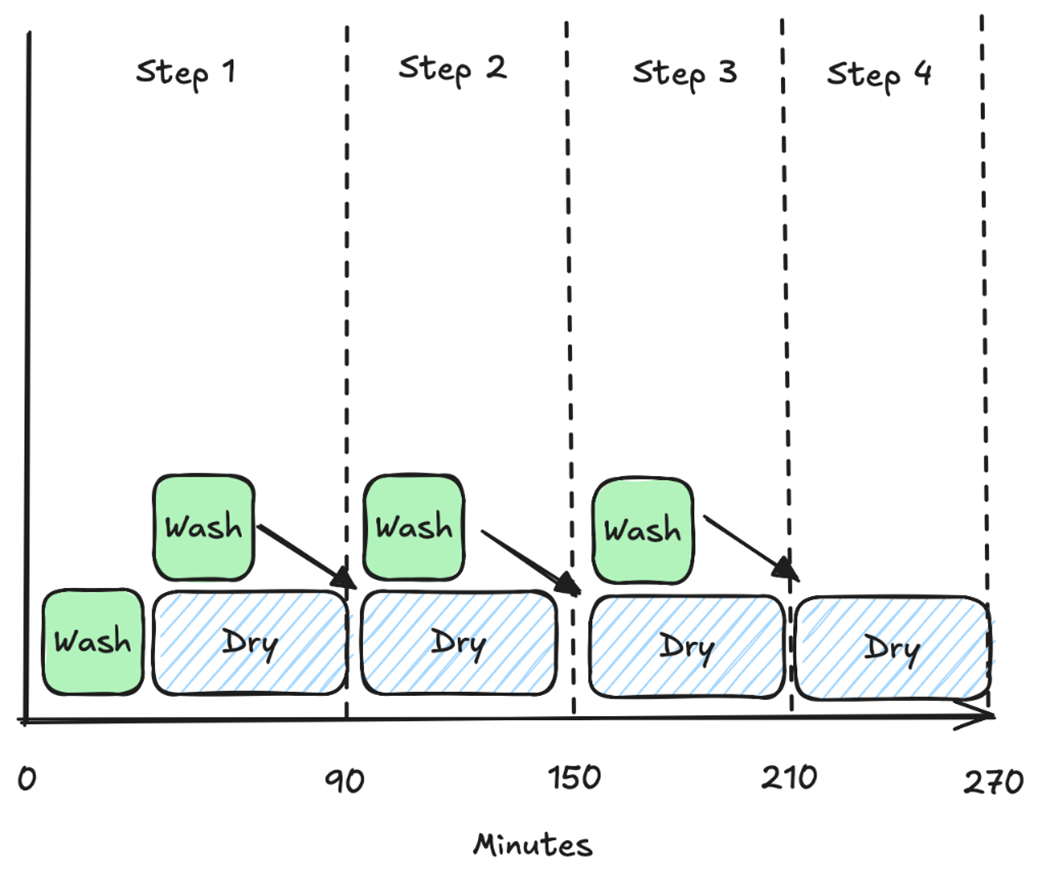

Processing with pipelining. We perform step W (washing) in full, but as soon as it completes, we start another step W. In parallel, we perform step D (drying) for the previous step W. If we ignore the initial step where there is no completed step W, the time to complete a load of laundry is 120 minutes because W and D run in parallel, but we’re bottlenecked by D, making latency worse than without pipelining. However, due to pipelining, we have now increased throughput to 1/60 loads of laundry per minute, which means that we can complete four loads of laundry in the same time as non-pipelined does three.

Summary

- Latency is the time delay between a cause and its observed effect.

- Latency is measured in units of time.

- You need to understand the latency constants of your system when designing for low latency.

- Latency matters because people expect a real-time experience.

- When optimizing for latency, there are sometimes throughput and energy efficiency trade-offs.

Latency ebook for free

Latency ebook for free