1 Understanding data-oriented design

Game development pushes teams to deliver complex, responsive experiences under tight performance and time constraints. This chapter introduces Data-Oriented Design (DOD) as a practical, data-first way to meet those demands. By centering decisions on the shape and placement of data—rather than on object relationships—DOD targets three outcomes at once: faster execution on modern CPUs, simpler code that’s easier to reason about, and more consistent extensibility over a project’s lifetime. While the Entity Component System (ECS) pattern often accompanies DOD in engines like Unity, the chapter emphasizes that DOD is a way of thinking about data and transformations, not a single prescribed architecture.

The performance core of DOD is about aligning data layouts with how CPUs actually run code. Because accessing main memory is orders of magnitude slower than using the CPU’s L1 cache, the chapter shows how organizing related values contiguously improves cache hit rates and leverages cache line prefetching. Instead of bundling many unrelated fields into objects, DOD favors grouping like-with-like in contiguous arrays (e.g., positions, directions, velocities), then operating over them in tight loops. This structure of arrays approach turns scattered memory fetches into predictable, sequential access, reduces cache misses, and can multiply throughput for common game loops such as moving large numbers of entities each frame.

Beyond speed, DOD reduces complexity by separating data from logic and treating functions as transformations: input data goes in, transformed data comes out. This mindset avoids deep inheritance trees and “who-owns-what” entanglements common in OOP, which tend to grow brittle as designers invent new behaviors. By solving for data—identifying exactly which fields a feature needs and passing them explicitly—teams keep changes localized and costs stable over time, even as content scales. ECS can be a convenient way to apply these ideas, but it’s optional; the key is data locality, explicit inputs/outputs, and iteration patterns that match hardware realities. The result is code that is naturally performant, more readable, and easier to extend throughout a game’s development.

Screenshot from our imaginary survival game, with the player in the middle, and enemies moving around.

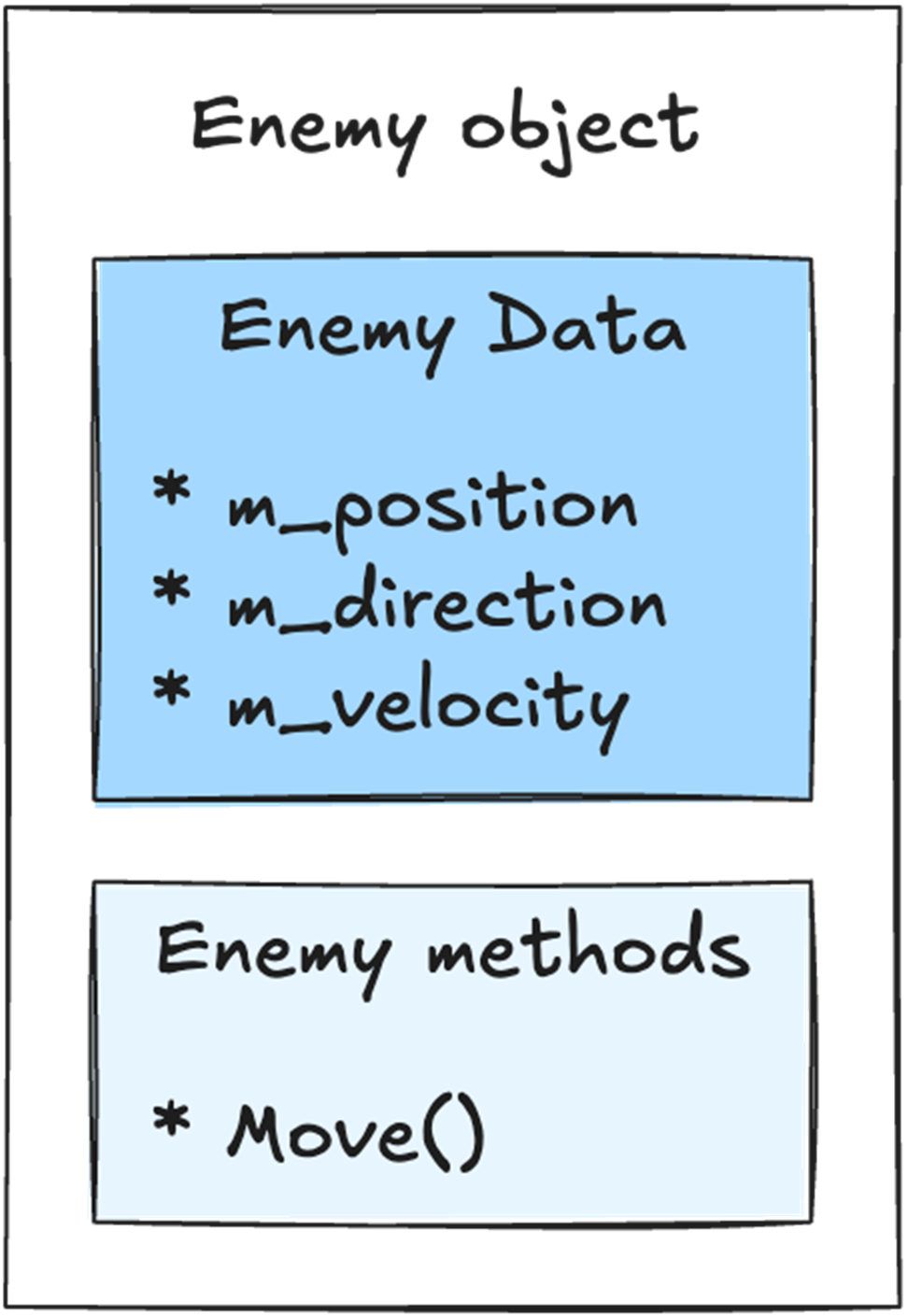

Our Enemy object holds both the data and the logic in a single place. The data is the position, direction, and velocity. The logic is the Move() method that moves this enemy around.

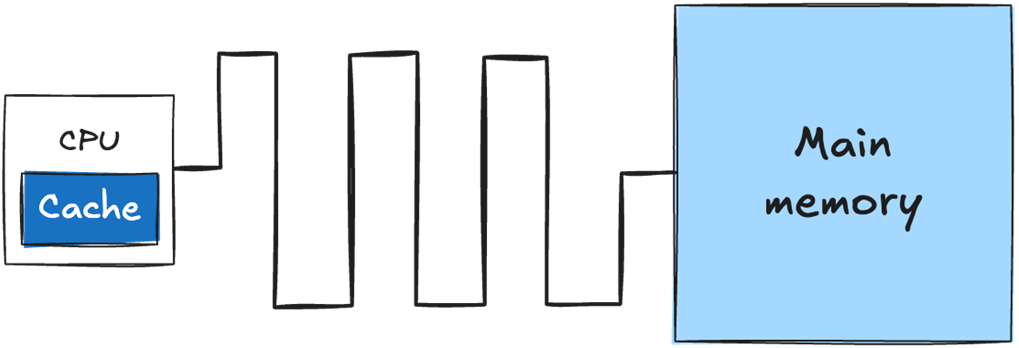

On the motherboard, the memory sits apart from the CPU, regardless if it’s in a console, desktop and mobile device. That physical distance, combined with the size of the memory, makes it relatively slow to retrieve data from memory.

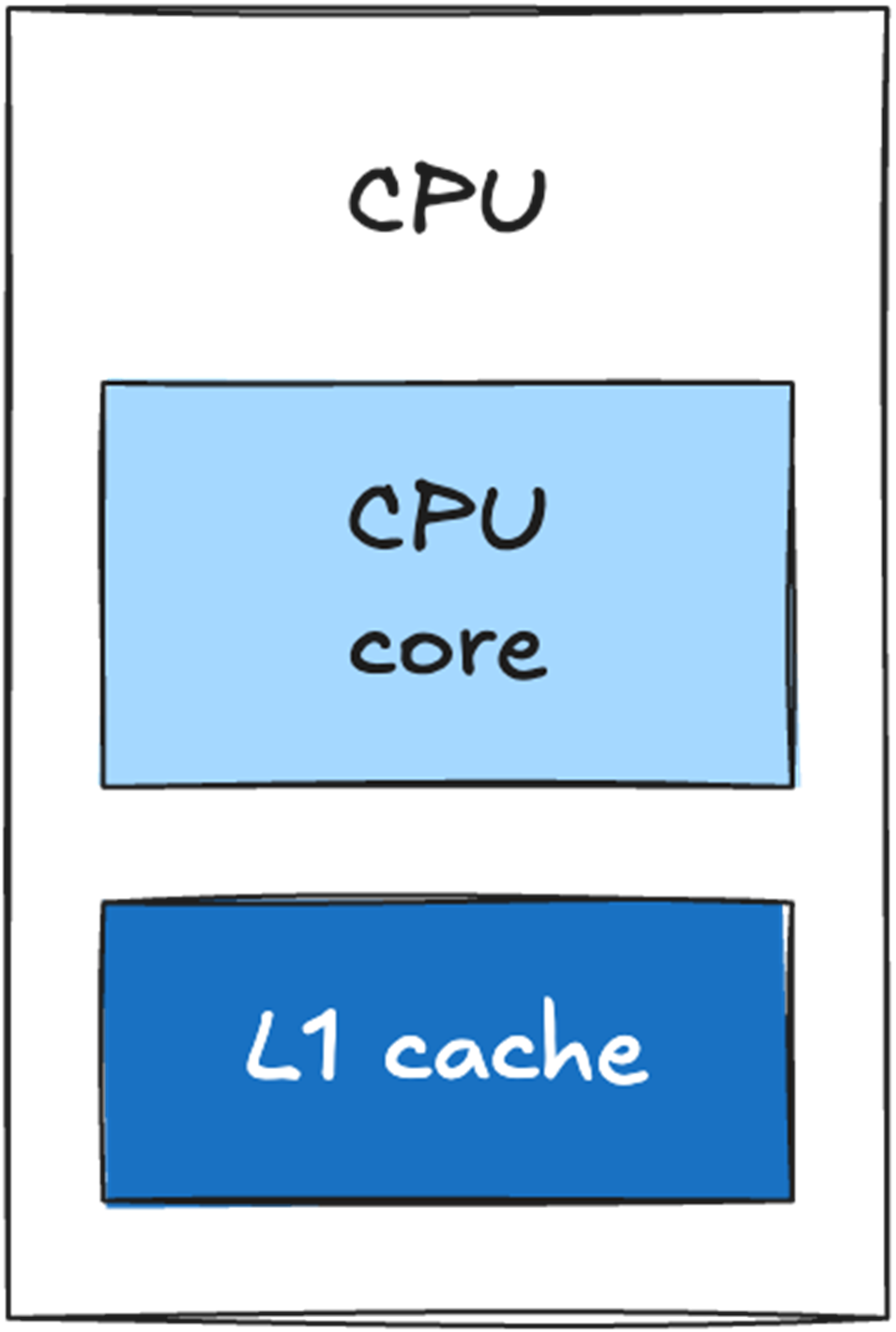

The cache sits directly on the CPU die and is physically small. Retrieving data from the cache is significantly faster than retrieving data from main memory.

A single-core CPU with an L1 cache directly on the CPU die.

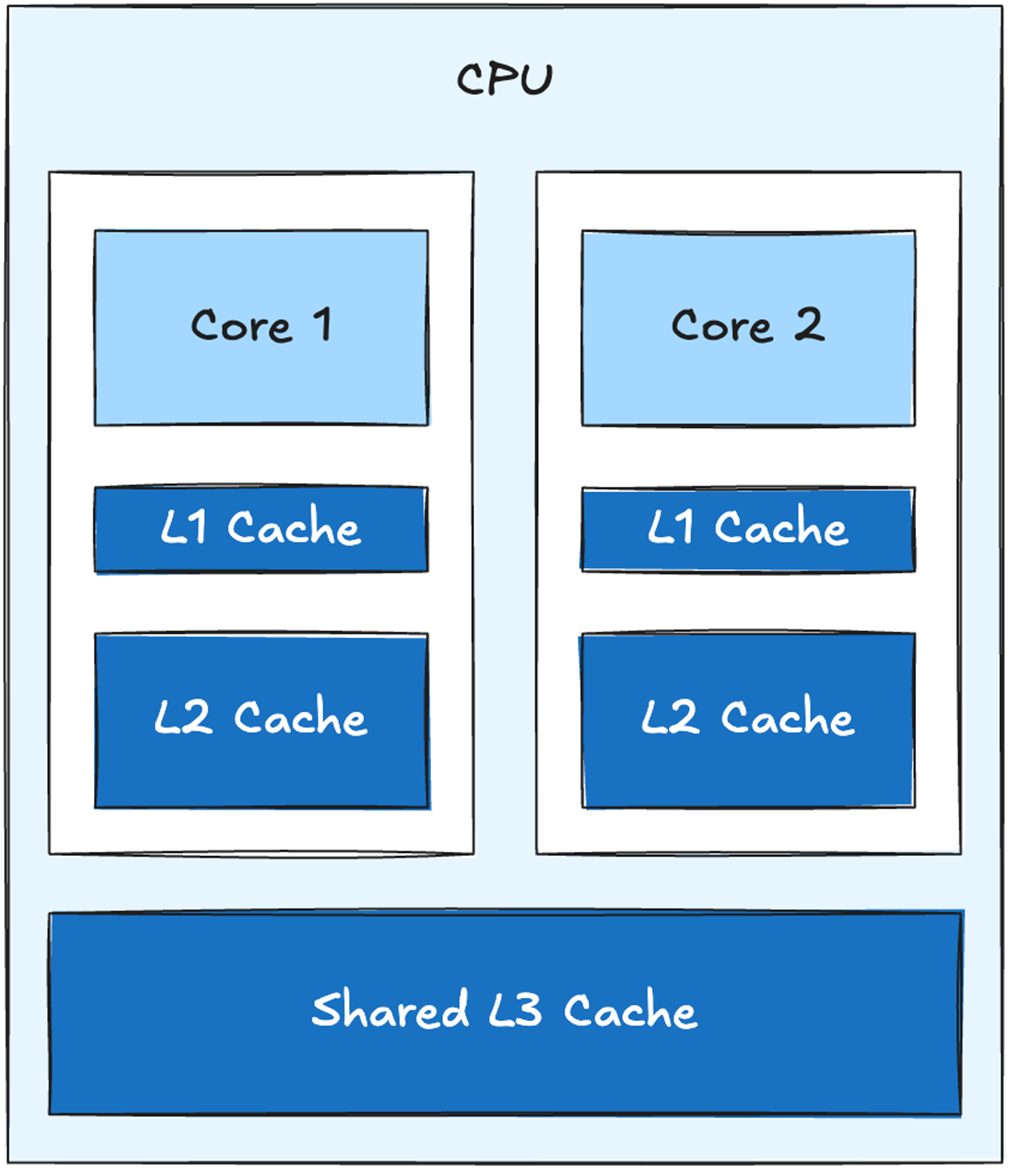

A 2-core CPU with shared L3 cache

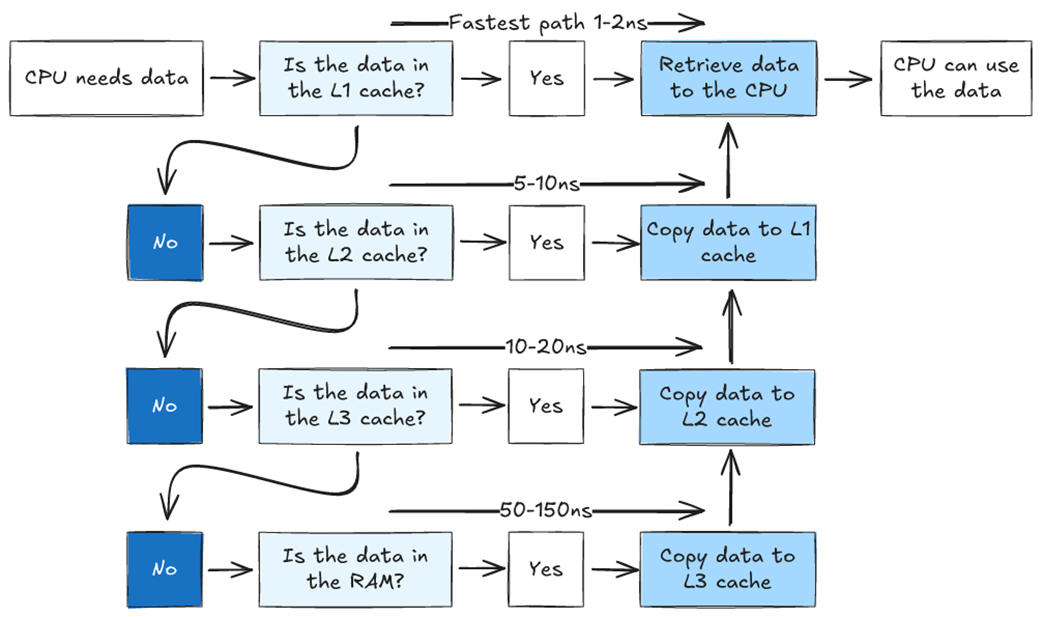

Flowchart showing how the CPU accesses data in a system with three cache levels. If the data is not found in the L1 cache, we look for it in L2. If it is not in L2, we look in L3. If it is not in L3, we need to retrieve it from main memory. The further we have to go to find our data, the longer it takes.

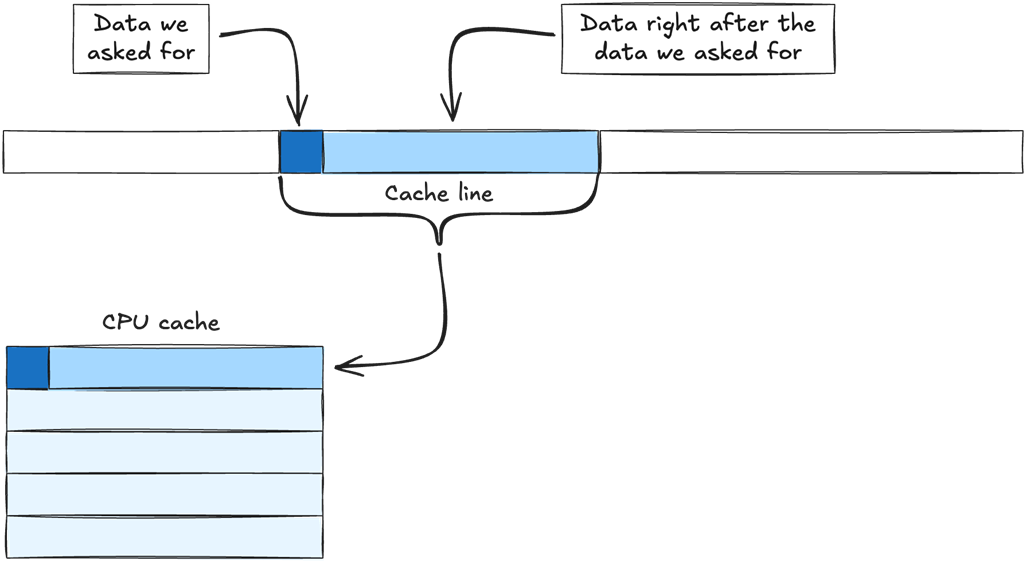

Data is retrieved from main memory in chunks called cache lines. When we ask for data from main memory, the memory manager retrieves the data we need, plus the chunk of data that comes directly after it, and copies the entire chunk to the cache.

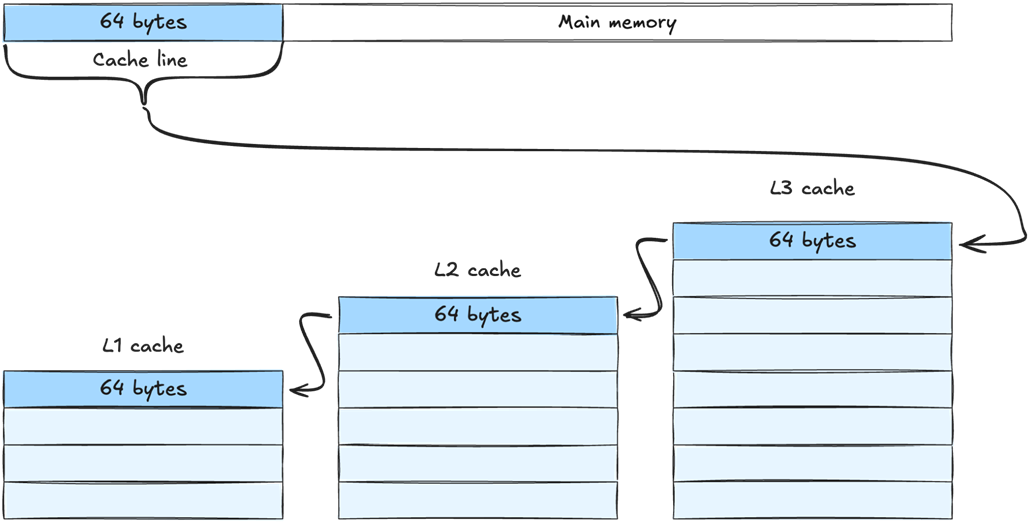

When retrieving a cache line from main memory, it is copied to all levels of the cache. In this example it is first copied to L3, then L2 and finally L1. The cache line is the same size at all levels - meaning the same amount of data is copied to every level. L3 can simply hold more cache lines than L2, and L2 can hold more cache lines than L1.

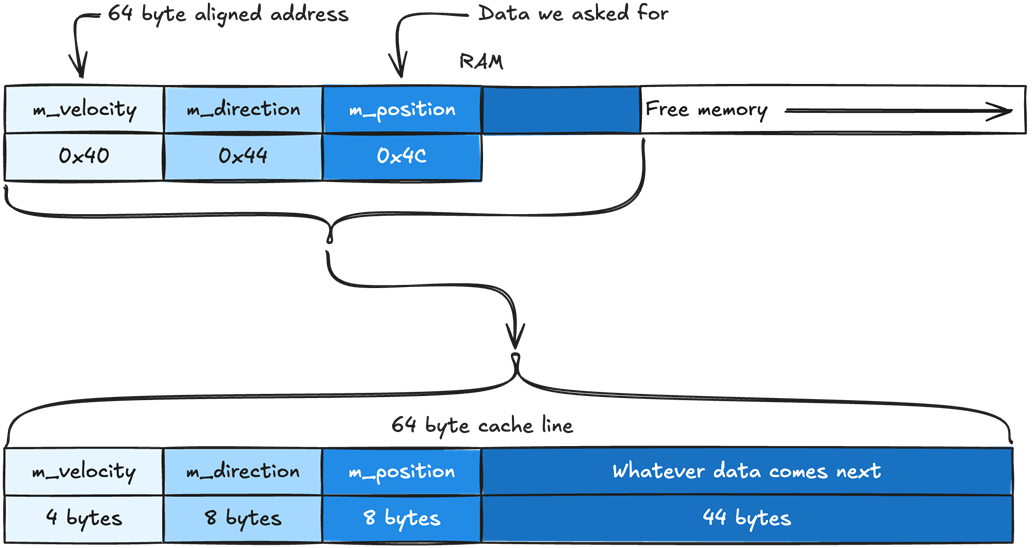

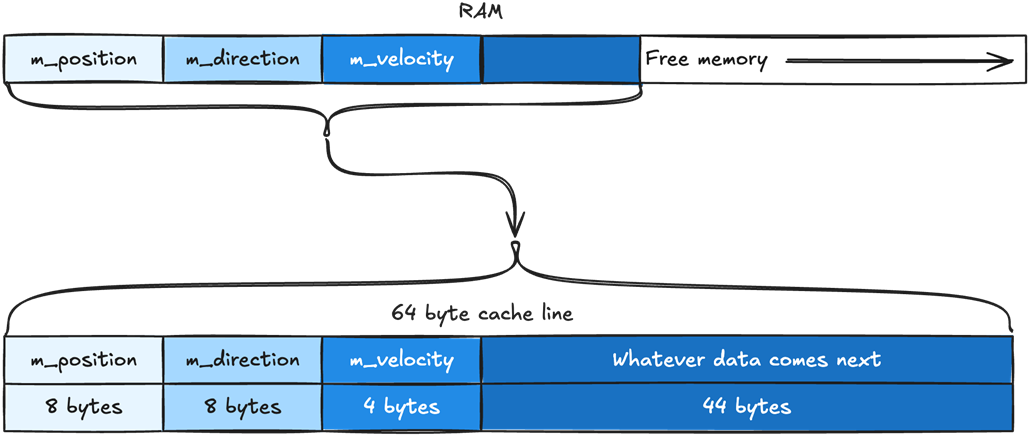

How the member variables of our Enemy object are placed in memory. The position data is placed first, then direction, then velocity. The same order they are defined in the Enemy class. They are packed together in memory without any space between them.

Our cache line will include m_position, m_direction, m_velocity, and whatever data comes right after them. Our cache line is 64 bytes. The variables m_position and m_direction are of type Vector2, which takes 8 bytes. The variable m_velocity is a float, which takes 4 bytes. That means we have 44 bytes leftover, which are automatically filled with whatever data comes after m_velocity.

When our CPU asks for m_position, the Memory Management Unit (MMU) will try to fill the cache line from the nearest address that is aligned with the size of our cache line. If our cache lines are 64-byte long, the cache line will be filled with data from the nearest 64-byte aligned address. In this case, m_position sits at 0x4C and the nearest 64-byte aligned address will be 0x40.

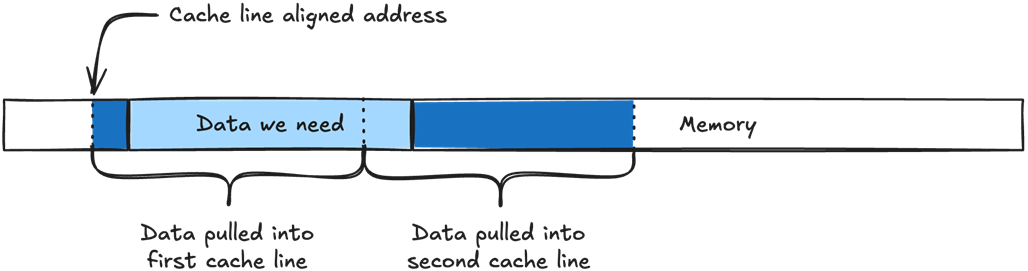

If the data we need does not align with the cache line size, it will need to be split into two cache lines instead of one.

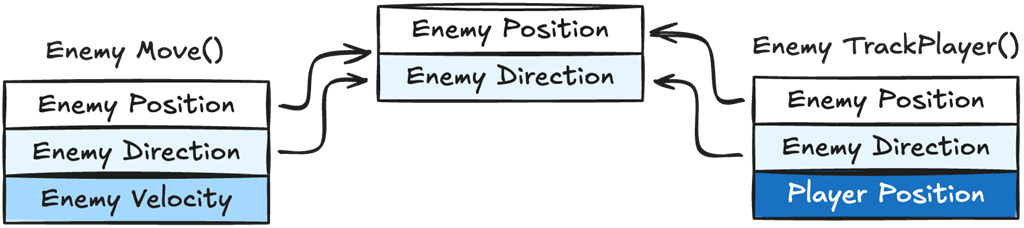

We can see both Move() and TrackPlayer() require the same variables, Enemy Position and Direction, but each one also needs different data as well, Enemy Velocity for Move() and Player Position for TrackPlayer(). When data is shared between different logic functions it makes it impossible to guarantee data locality for every logic function.

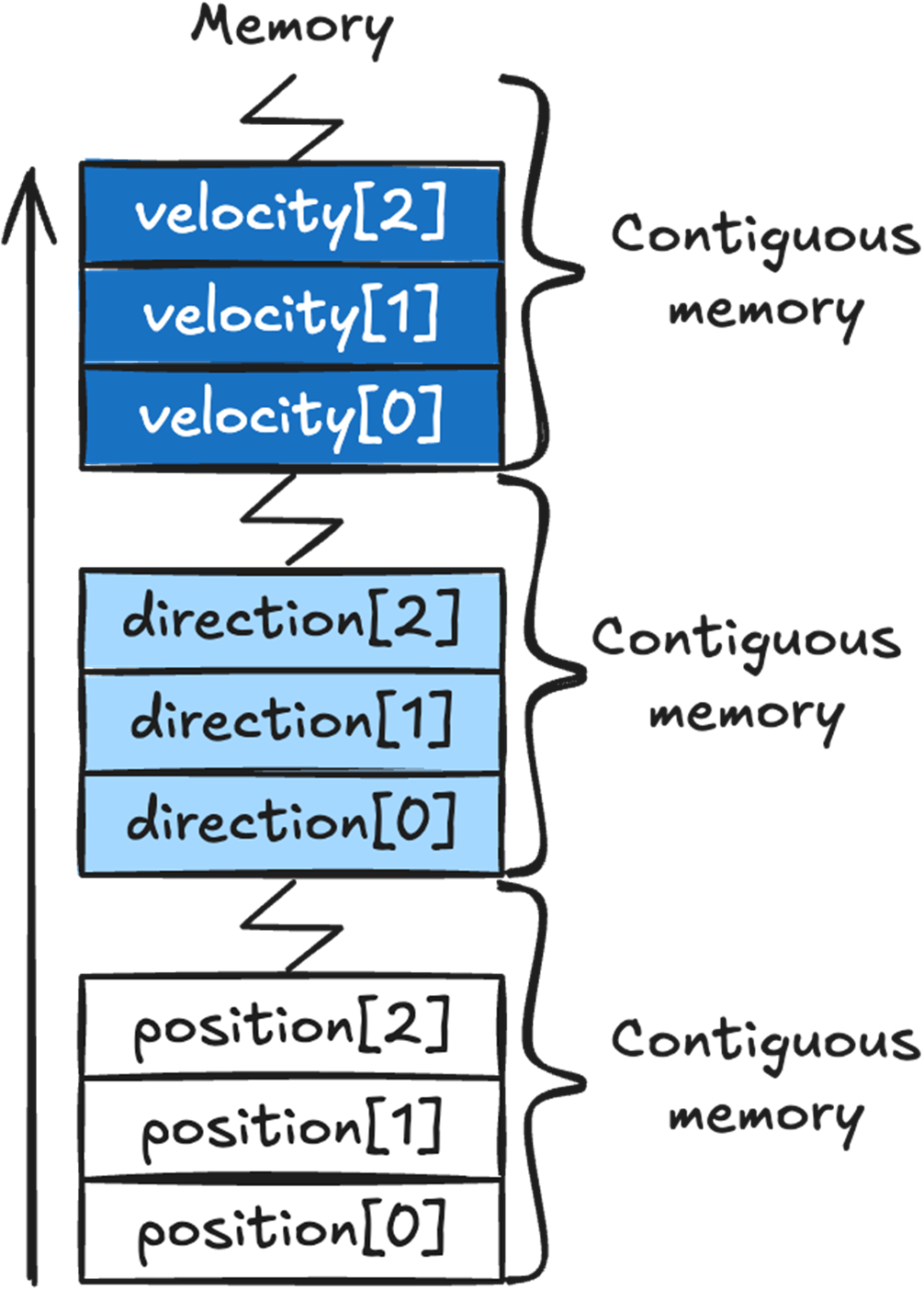

Arrays automatically place their data in contiguous memory. All the position array data will be in a single contiguous chunk of memory, as will direction and velocity’s data.

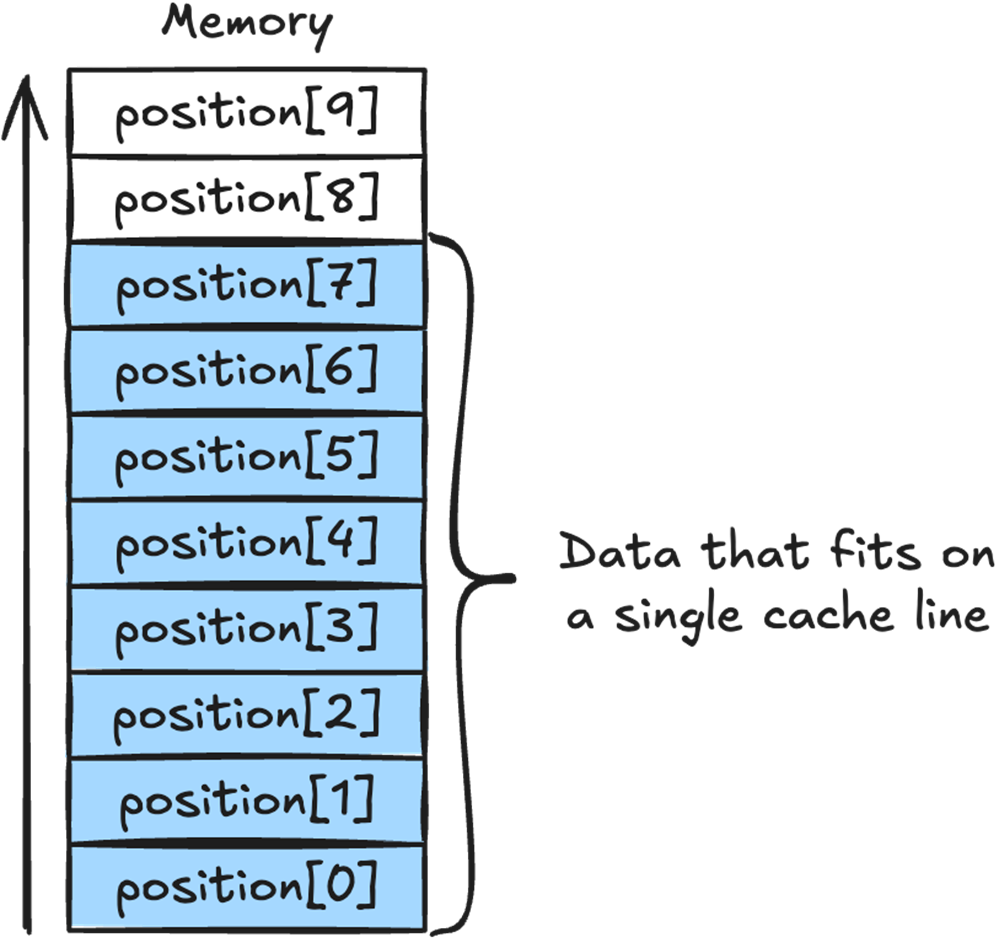

We can see how the position array sits in memory, and how the array elements 0 to 7 all fit in a single 64 byte cache line.

The two existing enemies in our game, the Angry Cactus, which is a static enemy, and the Zombie, which is a moving enemy.

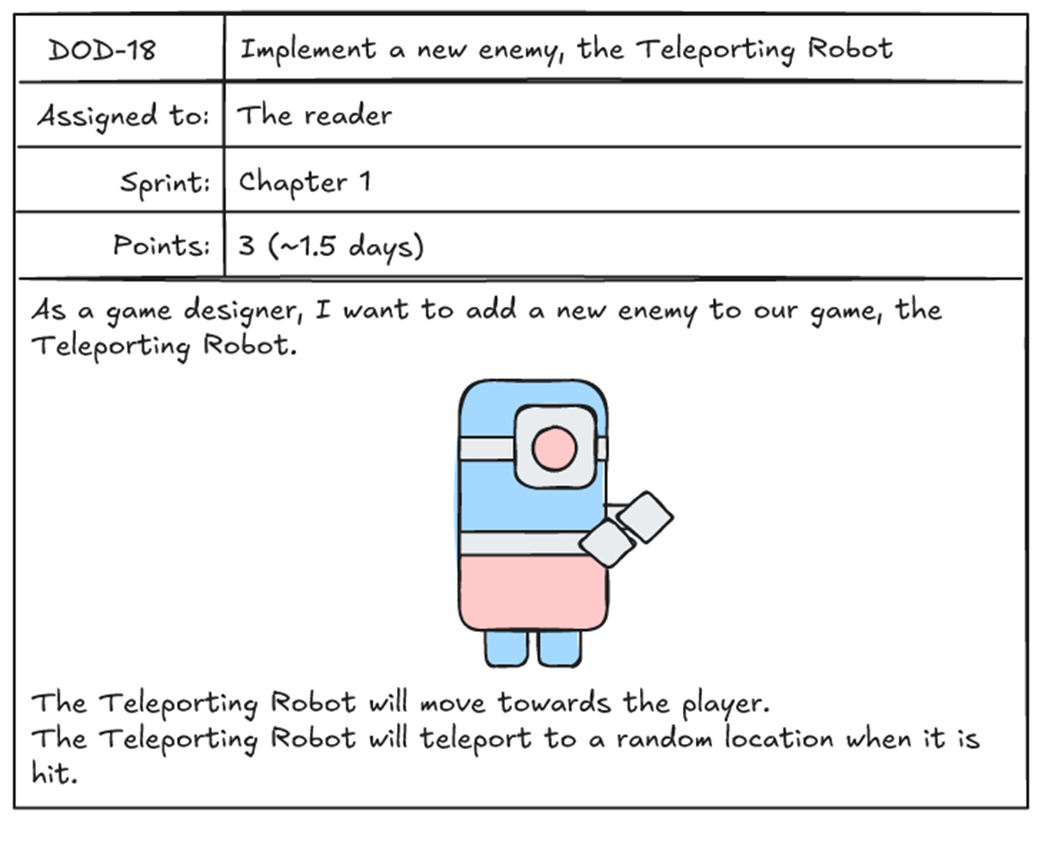

Task to implement a new enemy, the Teleporting Robot.

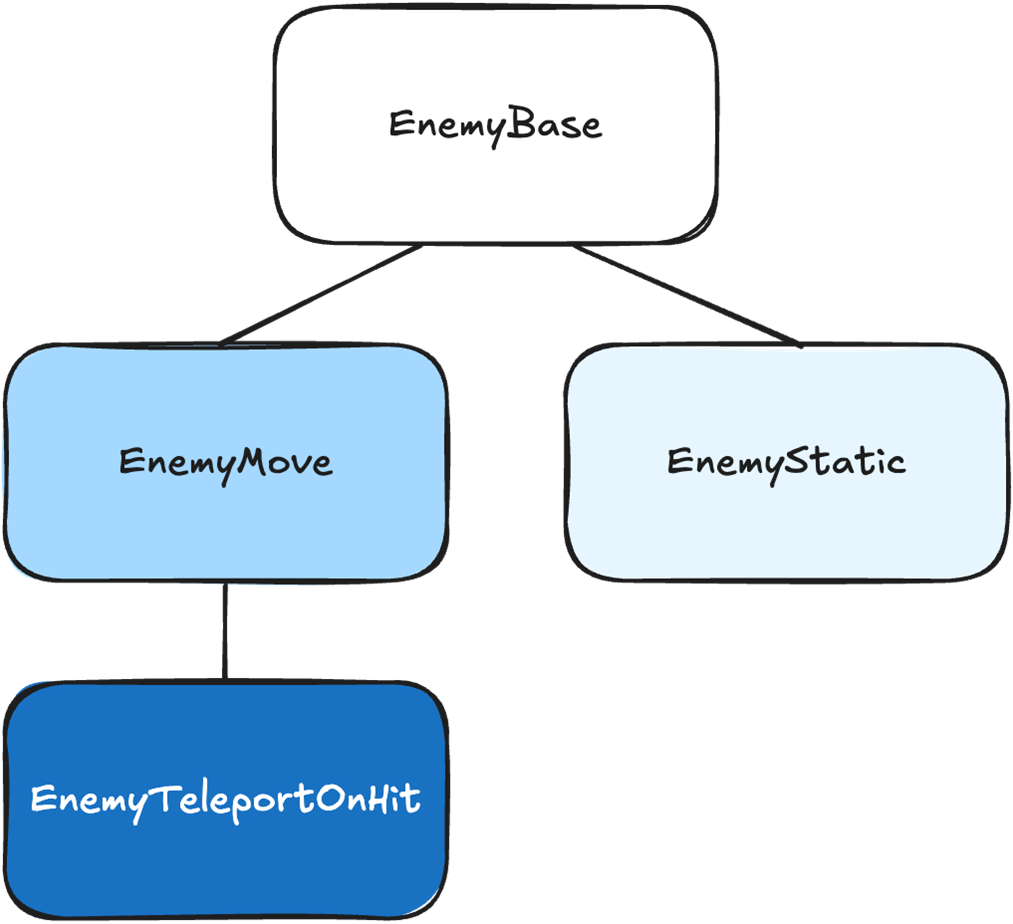

Our game’s enemy inheritance tree, with EnemyTeleportOnHit inheriting from EnemyMove.

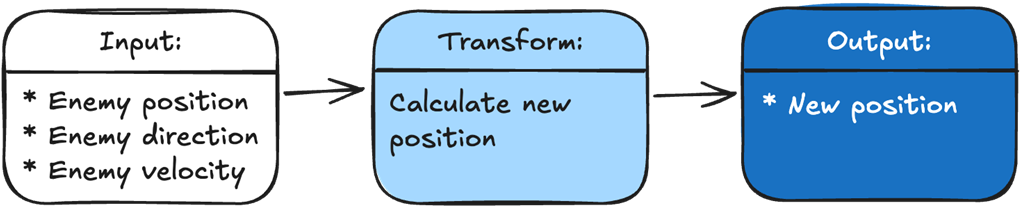

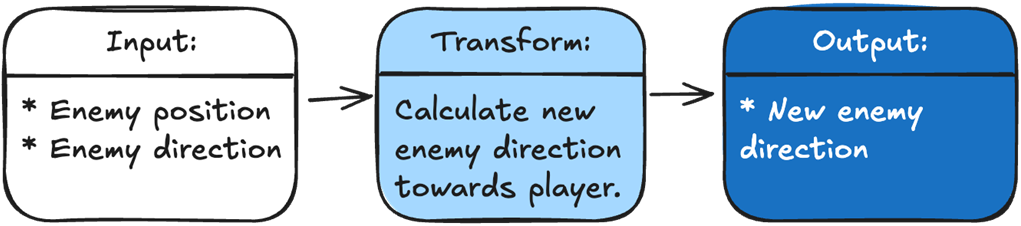

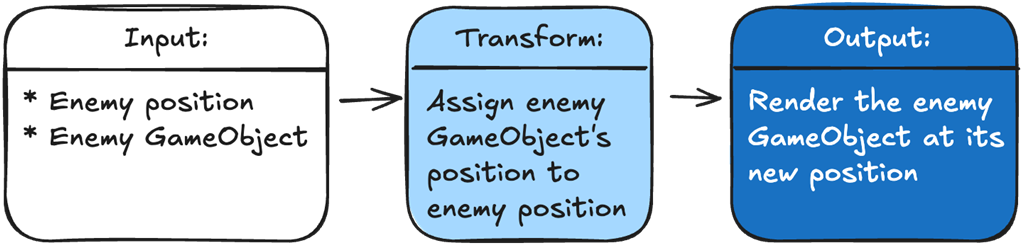

Every function in our game takes in some input data, then transforms it into output data.

The Move() function’s input is the enemy position, direction, and velocity. The transformation is our calculation of the new position. The output is the new position.

To make our enemy track the player, we just add a function that sets the enemy’s direction toward the player. Our input is the enemy position and the player position. The transformation is calculating a new direction for the enemy. The output is the new direction.

To add our new Robot Zombie, we just add a function that teleports the player to a new location if it is hit. Our input is the damage the enemy received, if any, and whether it should teleport if hit. The transformation is calculating a new position if the enemy is hit. The output is either the new position if hit, or the old position if the enemy is not hit.

To show an enemy in the correct position, we pass in the enemy’s GameObject and its position. We transform our data by assigning the GameObject’s position to the enemy. The output is Unity rendering our GameObject in the correct position.

Task to implement a new enemy, the Zombie Duck.

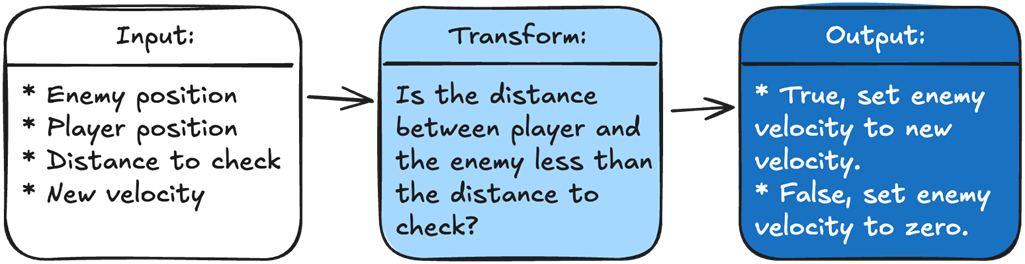

To determine what velocity we should set our enemy, we are going to take in four variables: the enemy position, the player position, the distance we need to check against, and the new enemy velocity. Our logic will calculate the distance between the player and the enemy and check it against the input distance. The output is the new velocity for the enemy based on the logic result.

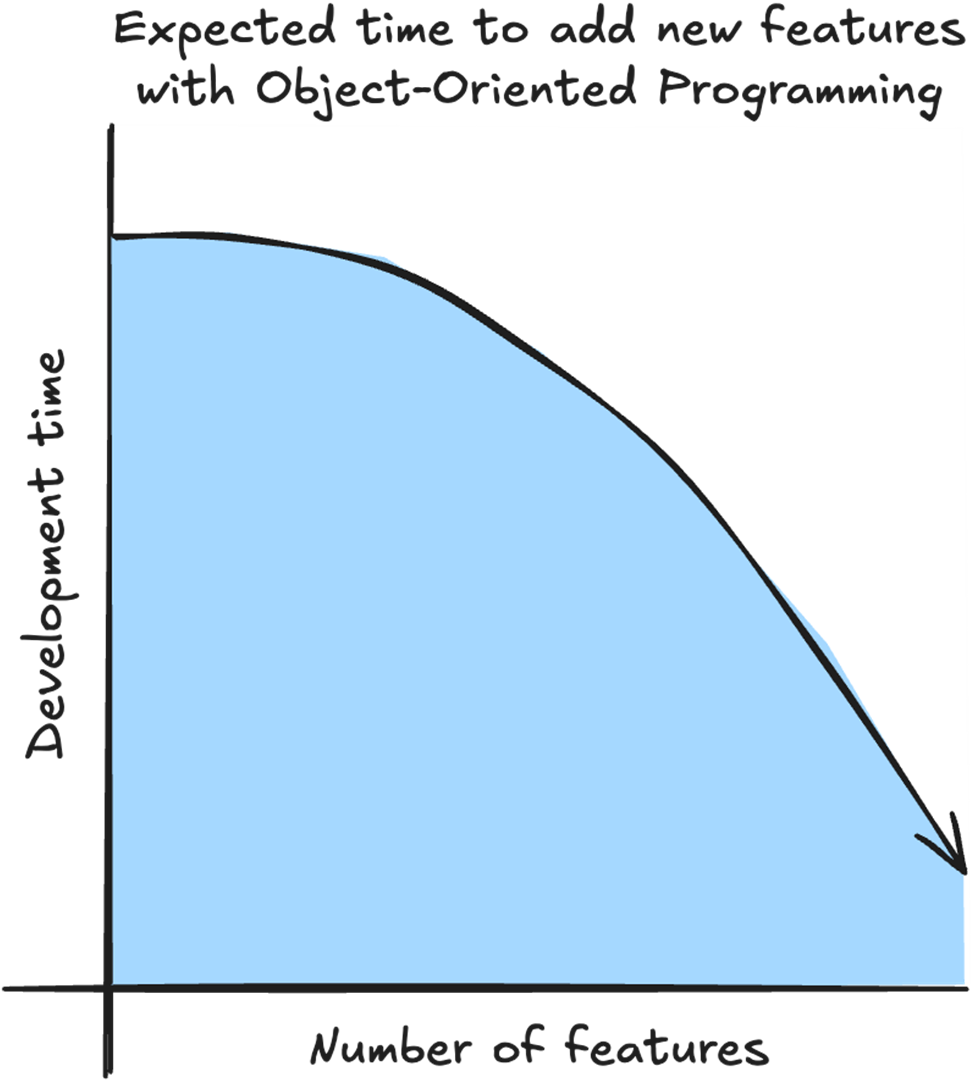

With OOP, in an ideal situation, we start the project by spending time setting up systems and inheritance hierarchies so future features will be quick and easy to implement.

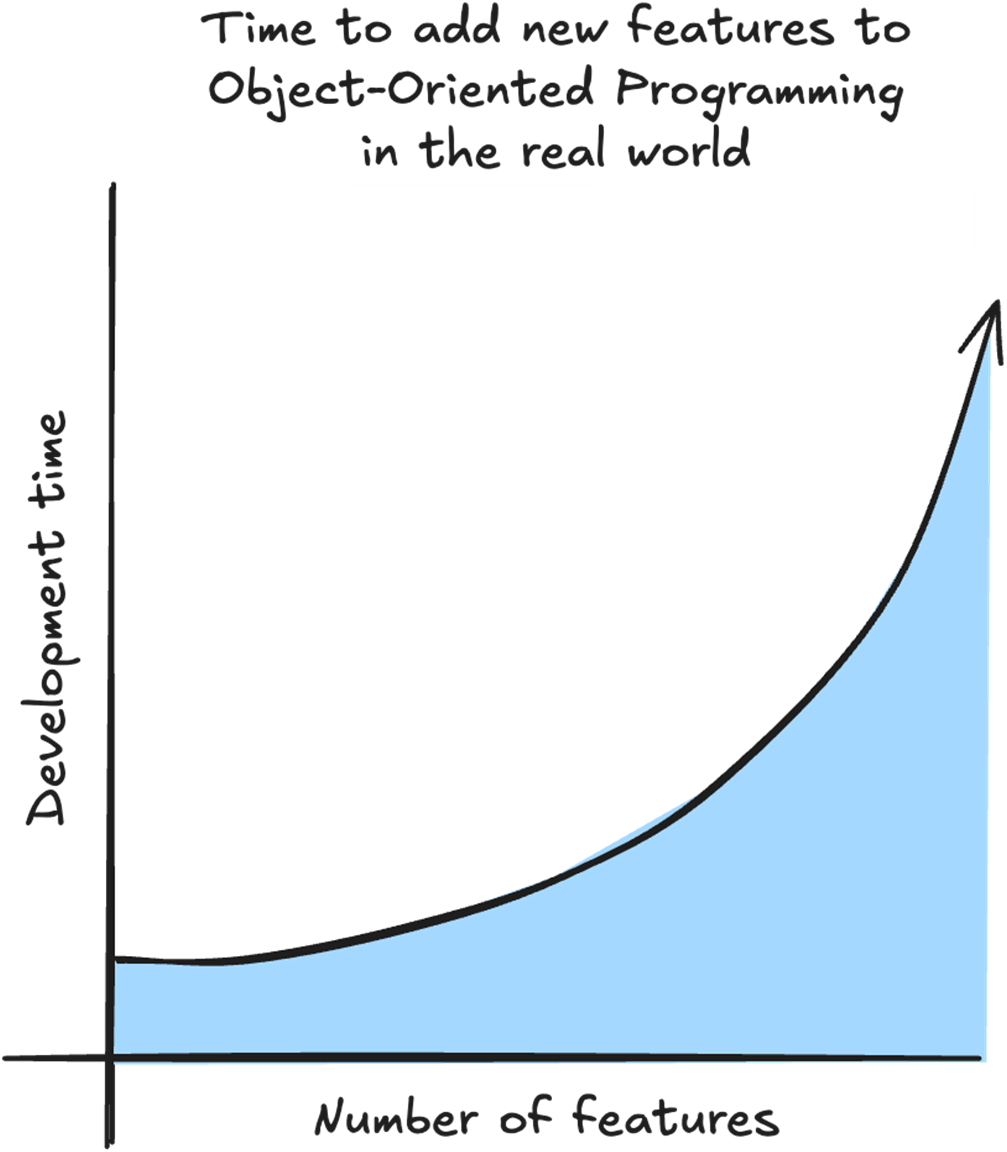

With OOP, what usually happens is that the more features we already have, the longer it takes to add a new feature. For every new feature, we need to take into account the complicated relationship between existing features.

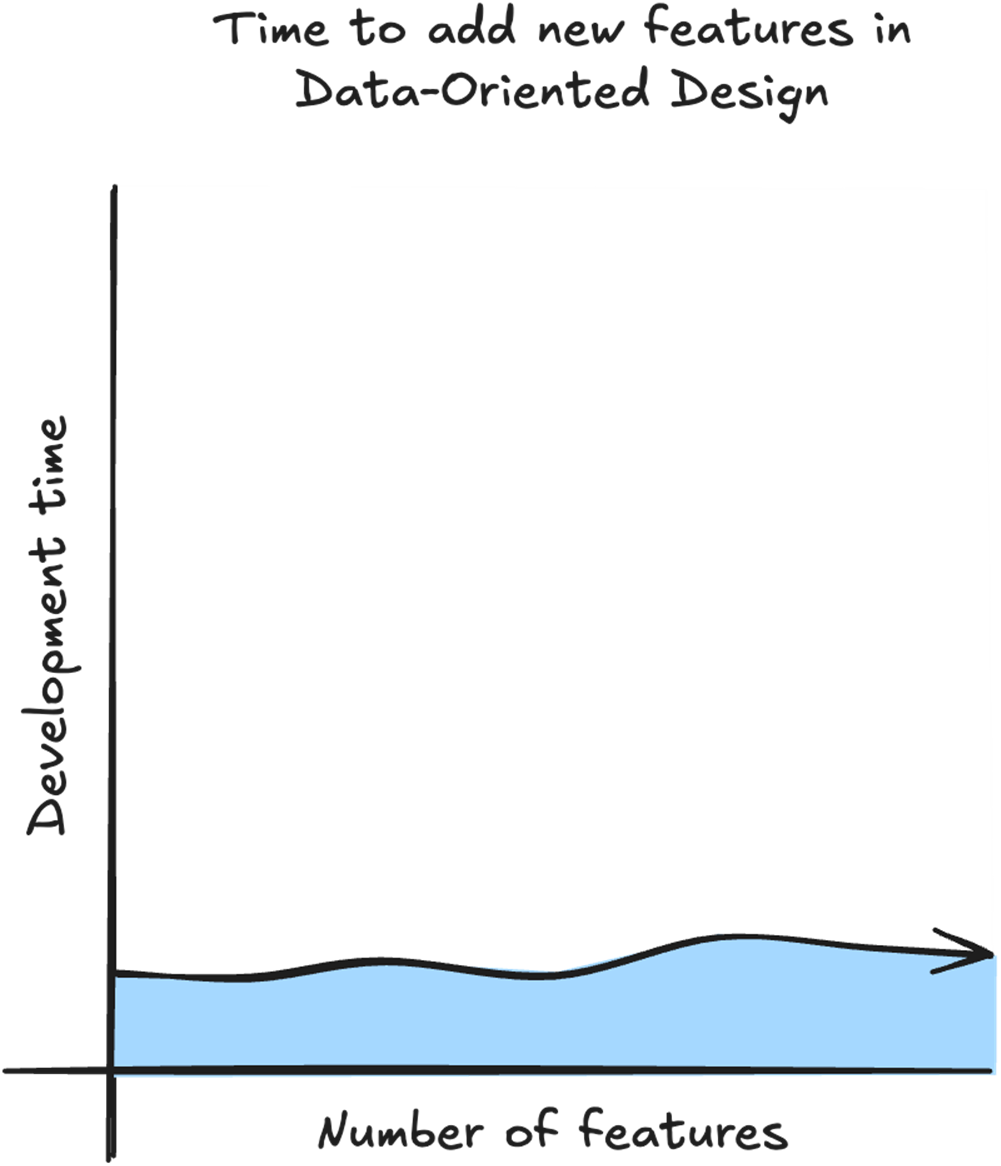

With DOD the time to add a new feature is linear because we don’t need to take into account the existing features. All we need is the data for the feature, and what logic we need to transform the data.

Summary

- With Data-Oriented Design we get a performance boost by structuring our data to take advantage of the CPU cache.

- Your target CPU may have multiple levels of cache, but the first level, called the L1 cache is the fastest.

- The L1 cache is the fastest because it is small and is placed directly on the CPU die.

- Retrieving data from L1 cache is up to 50 times faster than accessing main memory.

- To avoid having to retrieve data from main memory, our CPU uses cache prediction to guess which data we are going to need next and places it in the cache ahead of time.

- Data is pulled from memory into the cache in chunks called cache lines.

- Practicing data locality by keeping our data close together in memory helps the CPU cache prediction retrieve the data we’ll need in the future into the L1 cache.

- Placing our data in arrays makes it easy to practice data locality.

- With Data-Oriented Design we can reduce our code complexity by separating the data and the logic.

- Every function in our game takes input and transforms it into the output needed. The output can be anything from how many coins we have to showing enemies on the screen.

- Instead of thinking about objects and their relationships, we only think about what data our logic needs for input and what data our logic needs to output.

- With Data-Oriented Design, we can also improve our game's extensibility by always solving problems through data. This makes it easy to add new features and modify existing ones.

- Regardless of how complex our game has become, every new feature can be solved using data. This allows for near-constant development time regardless of how complex our game has become and makes it easy to add complicated new features.

- ECS is a design pattern sometimes used to implement DOD. Not all ECS implementations are DOD, and we don’t need ECS to implement DOD.

Data-Oriented Design for Games ebook for free

Data-Oriented Design for Games ebook for free