1 Algorithms & Data Structures

This chapter introduces foundational algorithms and data structures with a strong emphasis on understanding trade-offs between theoretical complexity and real-world performance. It highlights how choices like memory layout and access patterns affect cache behavior and instruction efficiency, and encourages benchmarking rather than relying solely on asymptotic analysis. The discussion spans linear collections, priority-oriented trees, and networked models of data, then connects them to common algorithmic techniques used in interviews and day-to-day engineering.

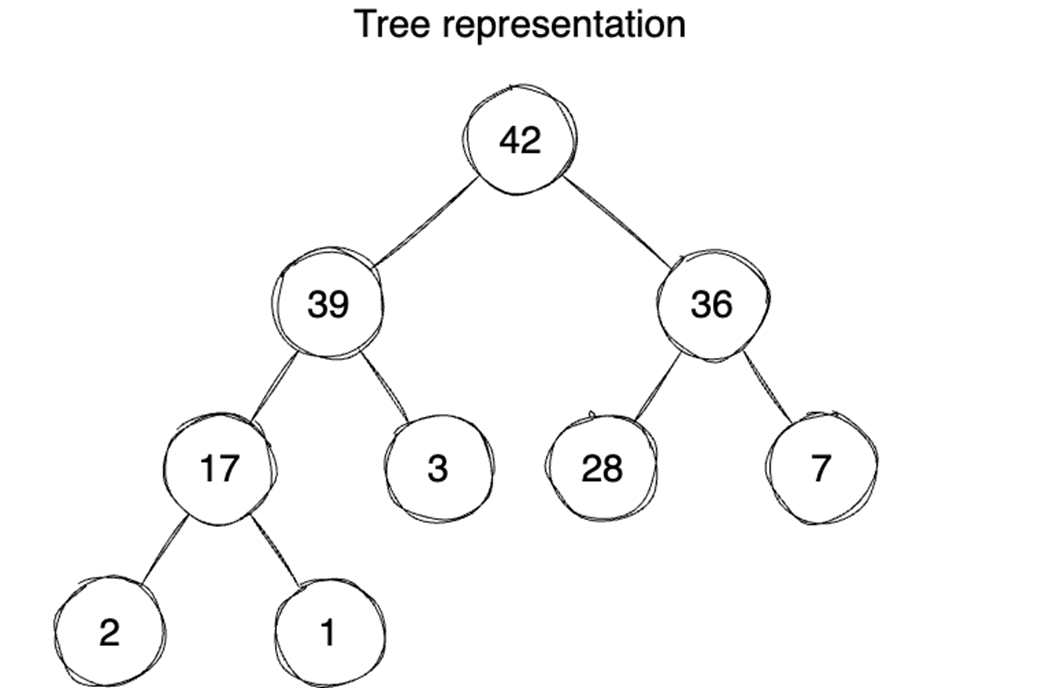

The chapter first contrasts arrays and linked lists: arrays provide contiguous storage with O(1) indexed access, while linked lists chain nodes via pointers, trading higher memory overhead and sequential access for flexible insertions/deletions. Although linked lists can offer favorable big-O for certain operations, arrays often outperform them in practice due to spatial locality, cache friendliness, and predictable iteration; even contiguously allocated linked lists can suffer from extra per-iteration overhead and poorer prefetching. It then presents binary heaps as complete binary trees (usually array-backed) that maintain a min- or max-heap property, enabling priority queues with insert/extract in O(log n), constant-time min/max lookup, and O(n) heap construction. Heaps frequently outperform binary search trees for priority access thanks to better locality and faster initialization.

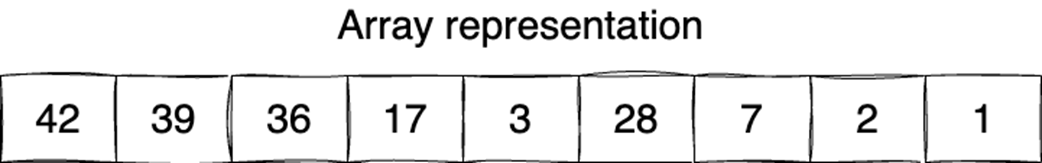

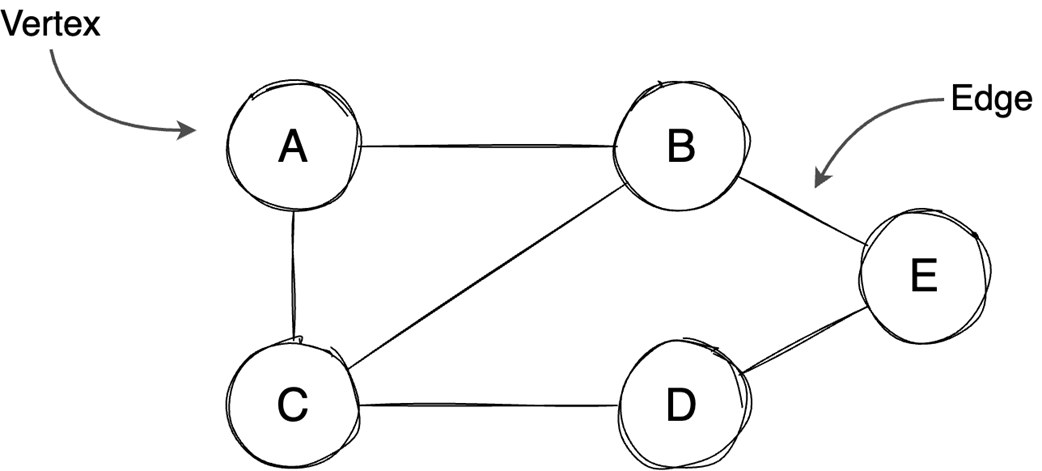

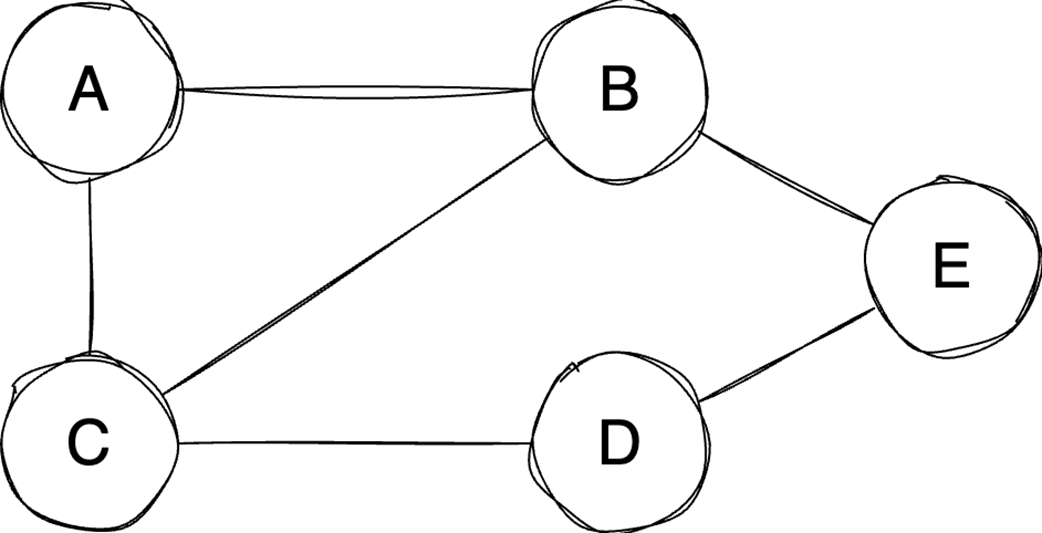

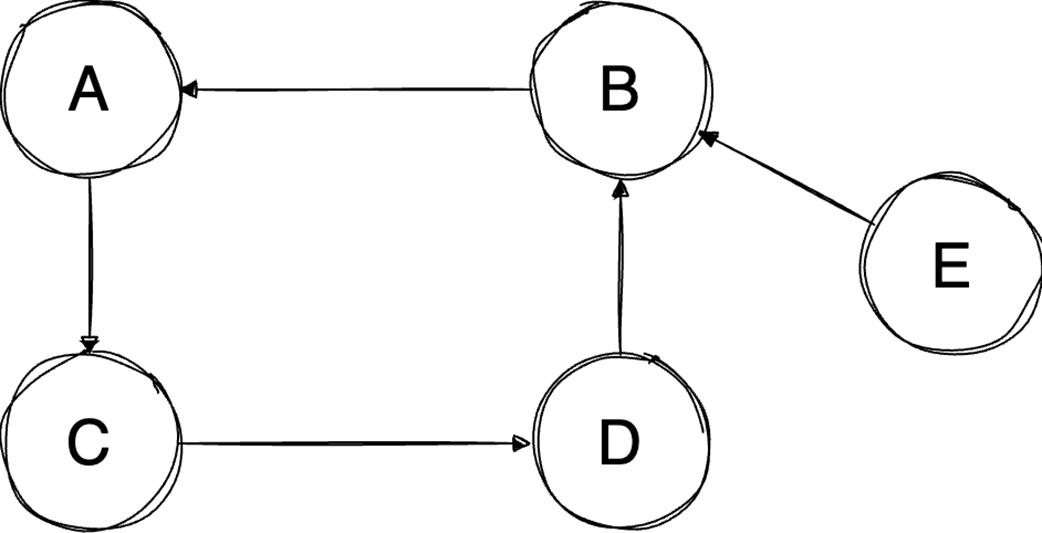

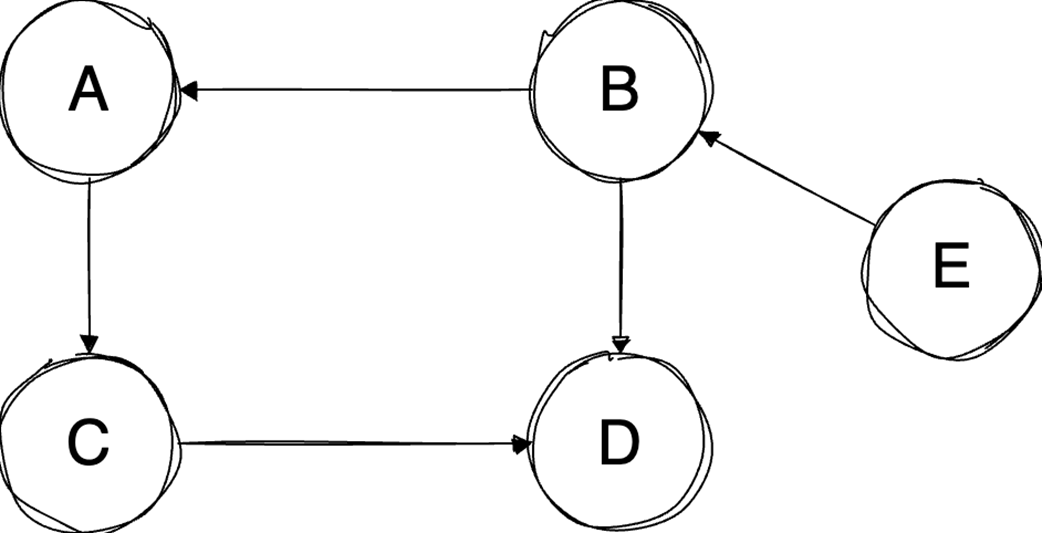

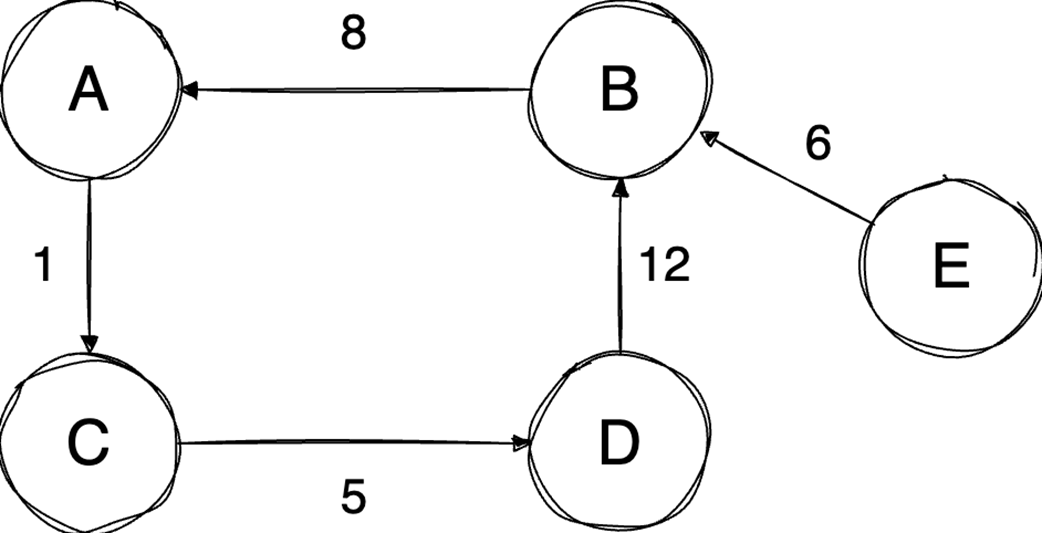

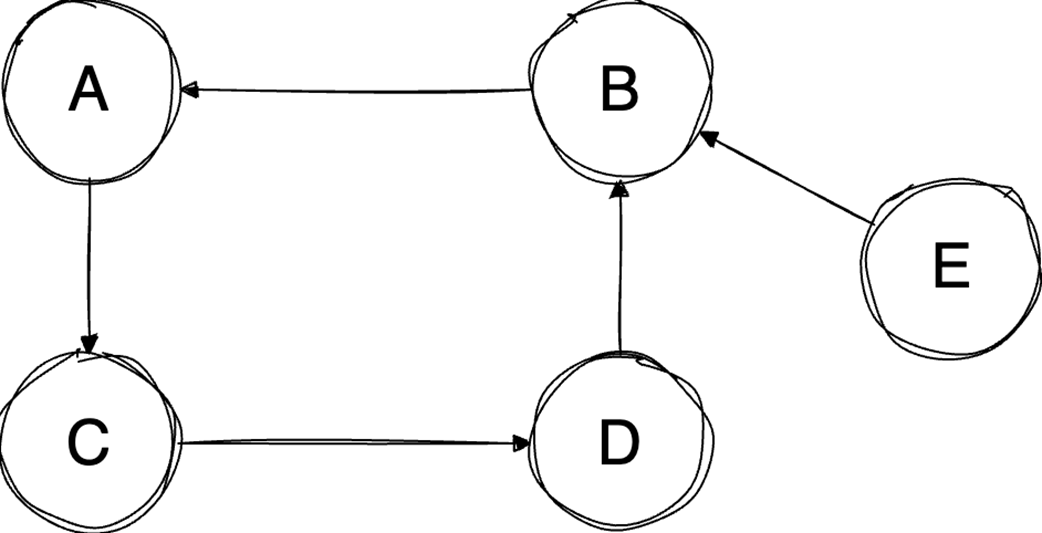

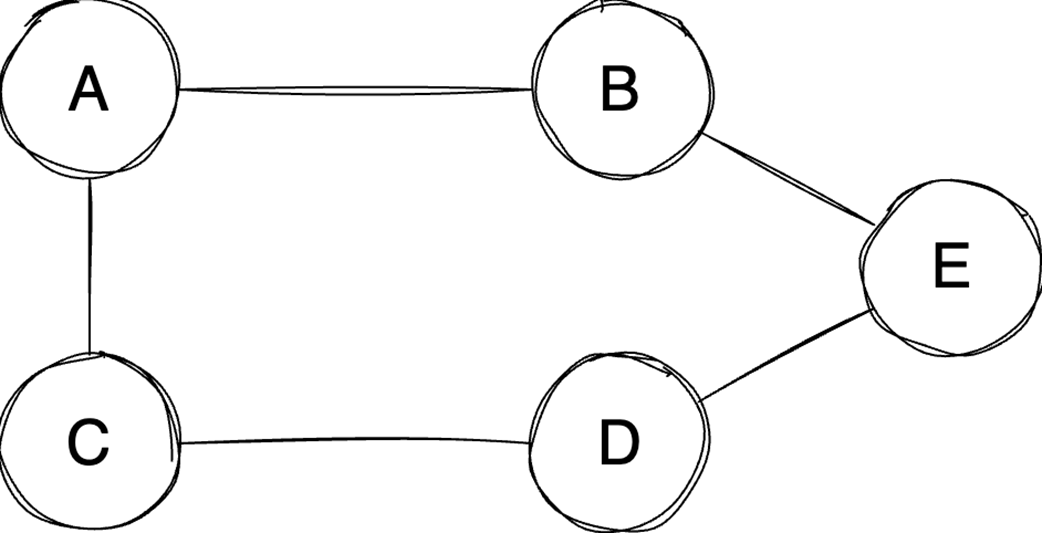

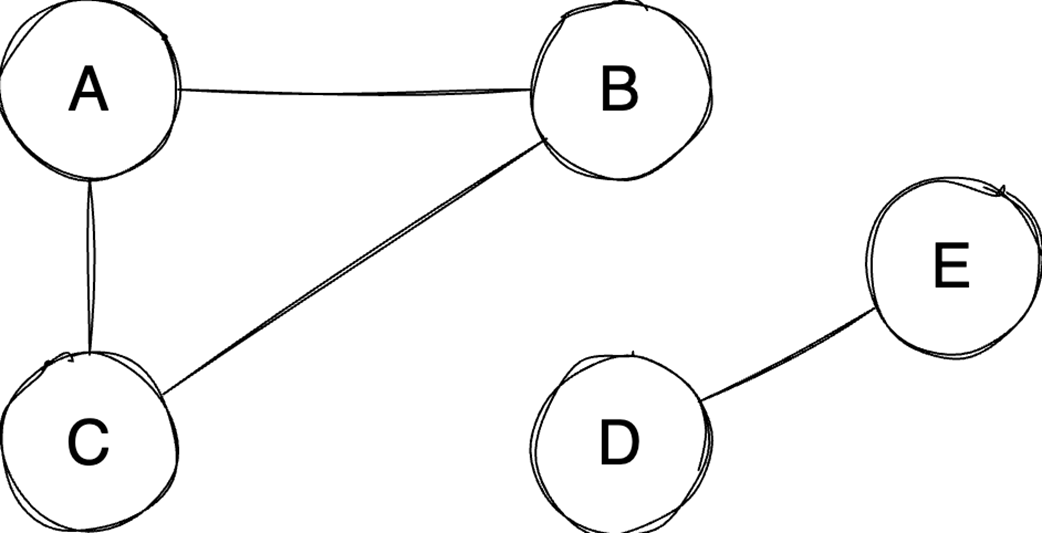

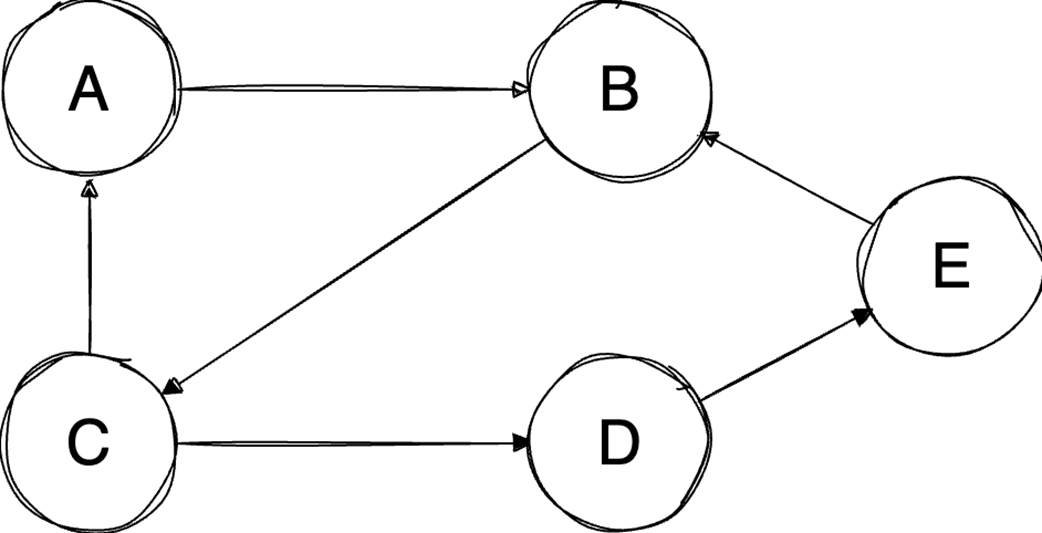

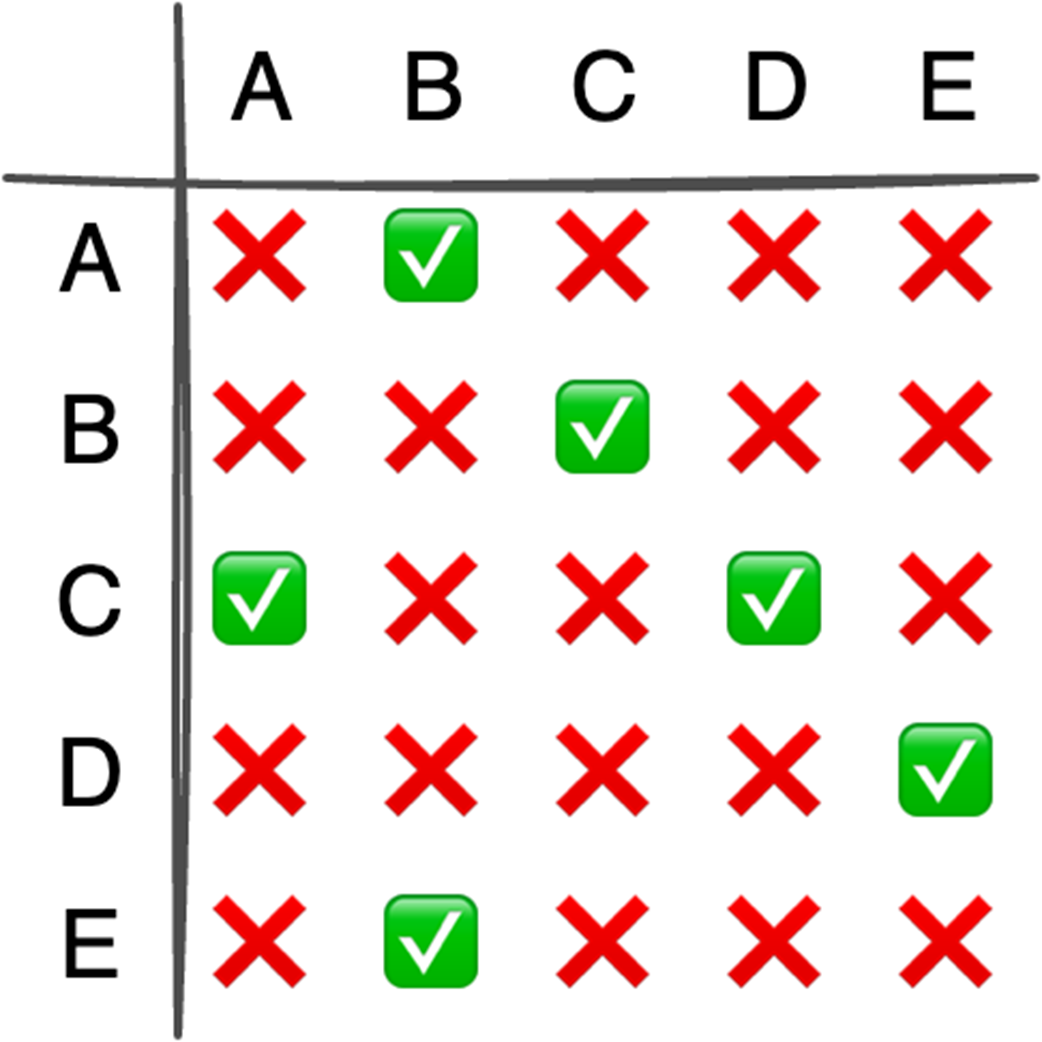

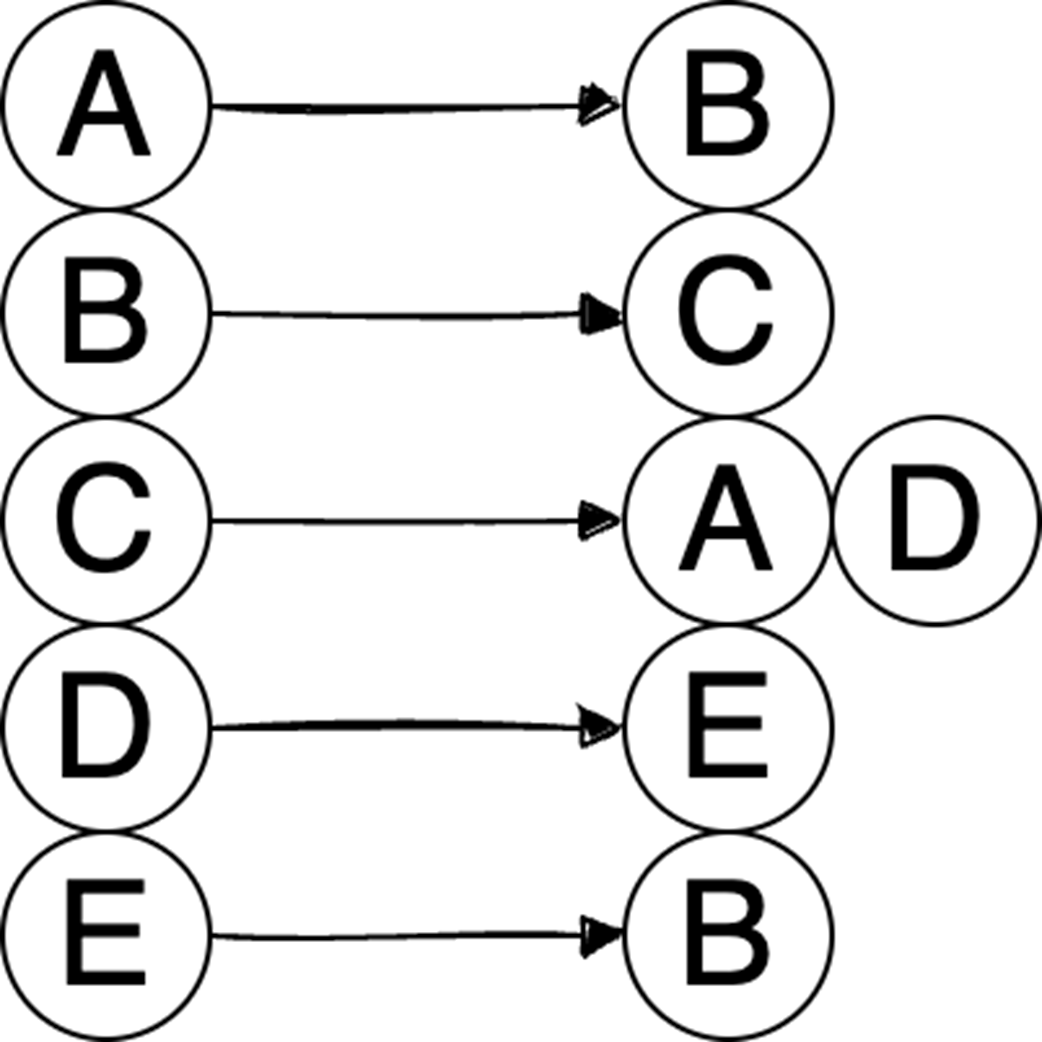

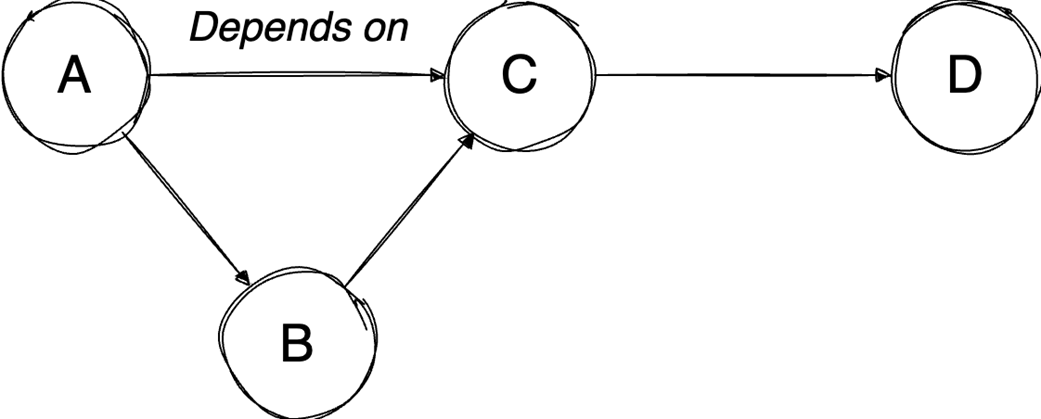

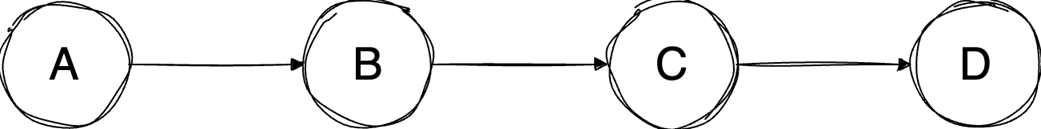

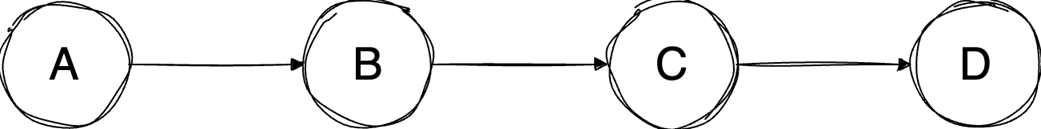

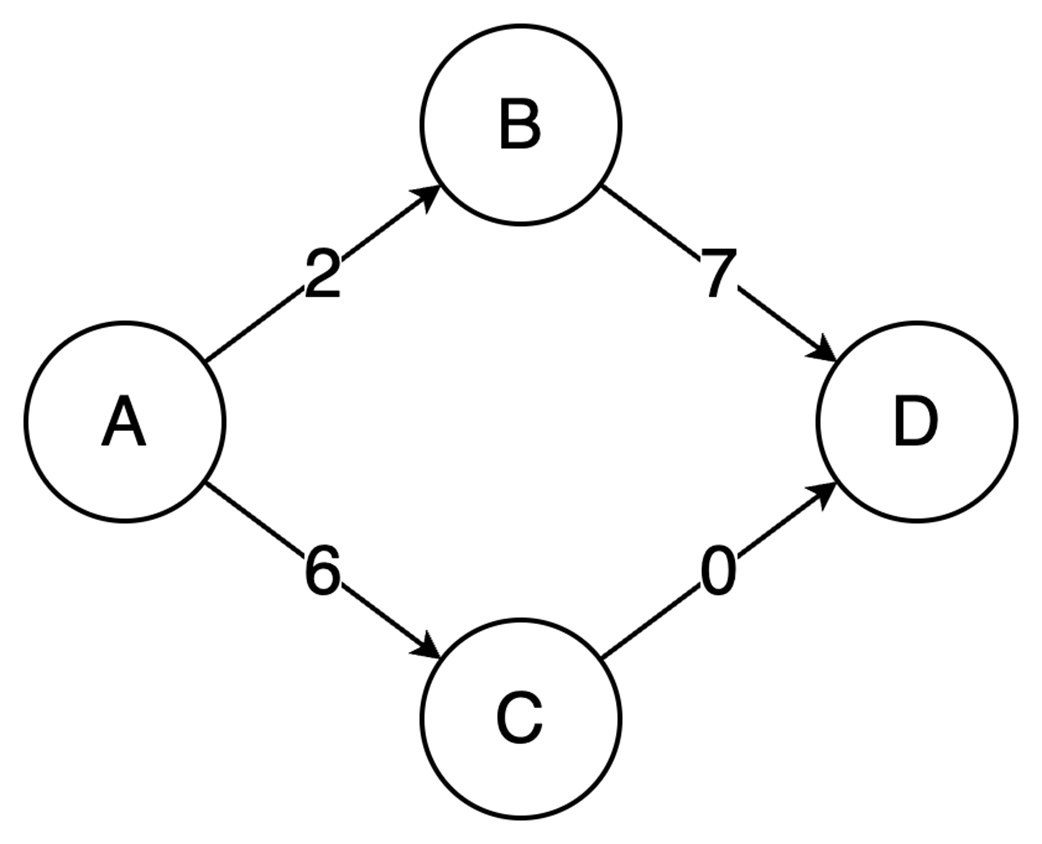

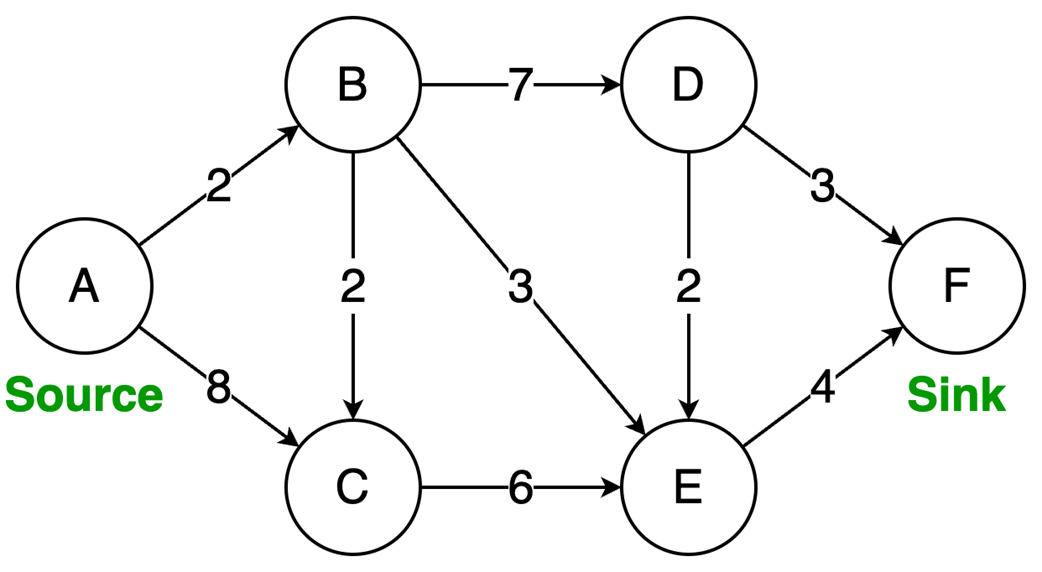

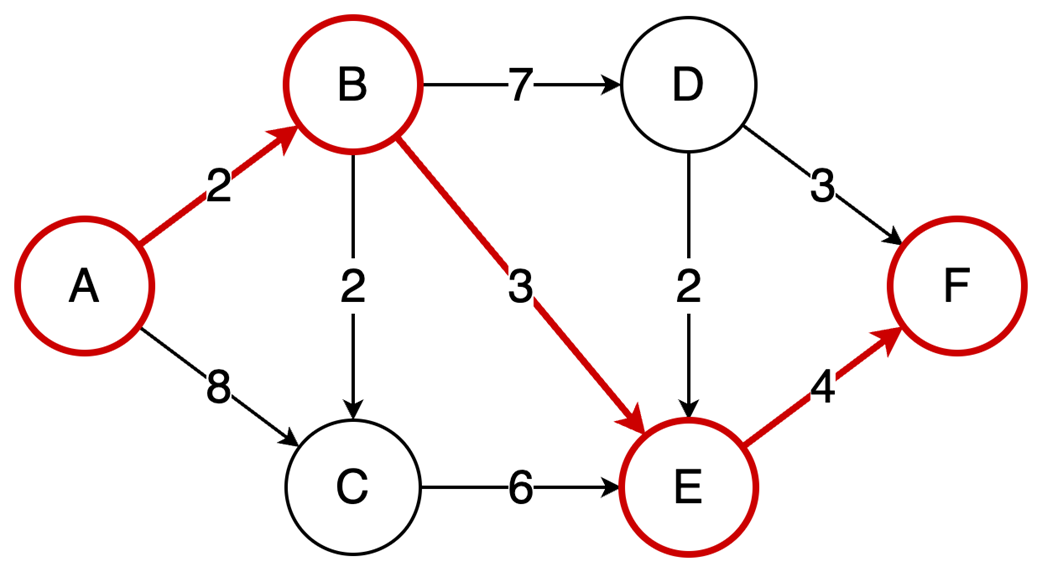

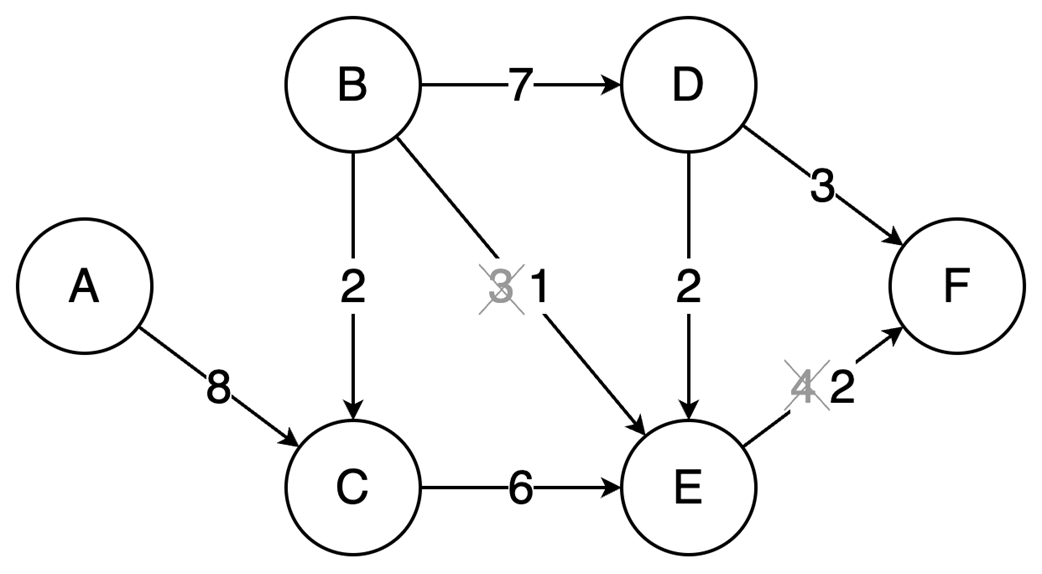

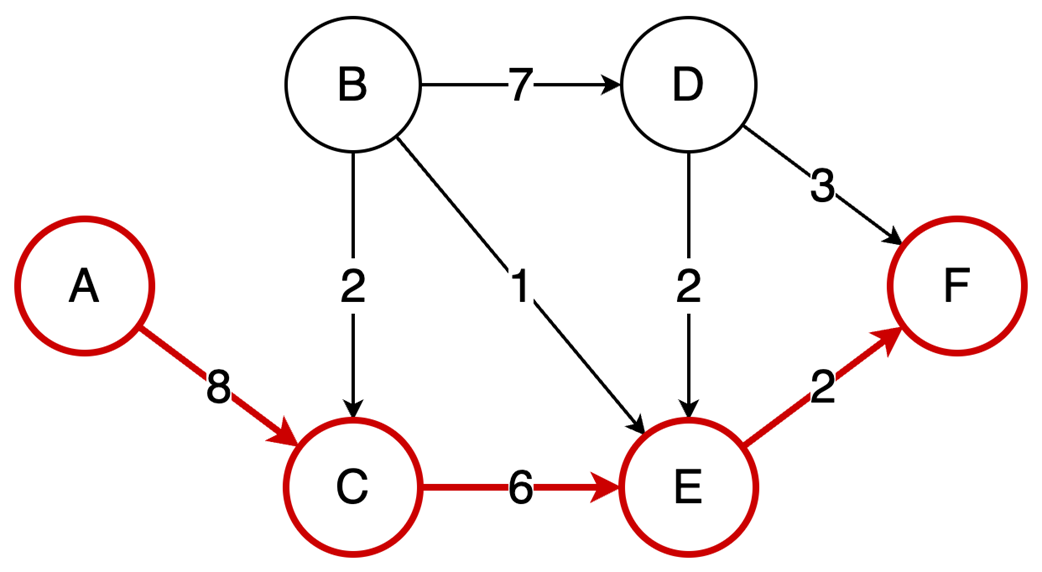

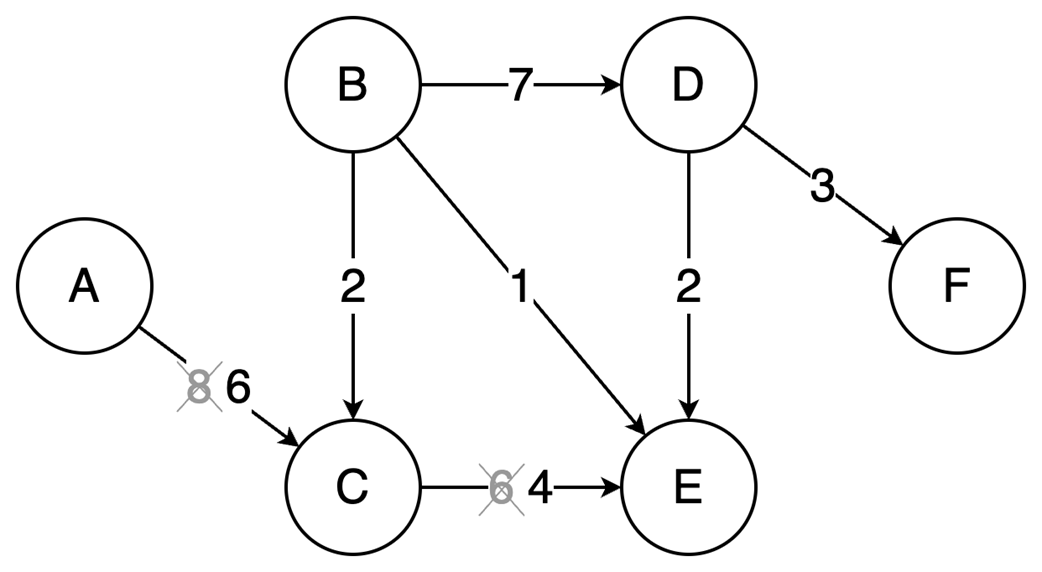

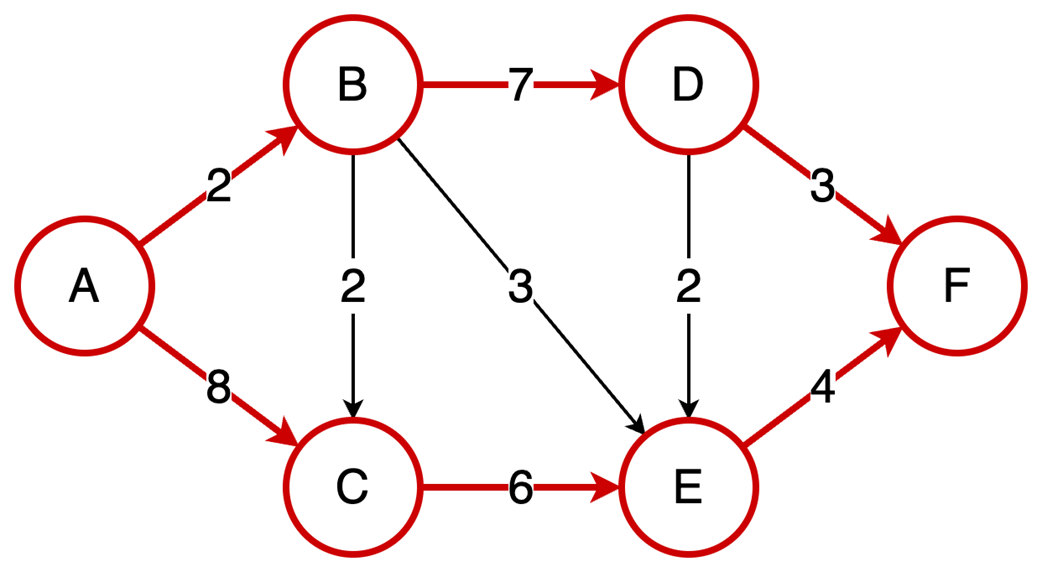

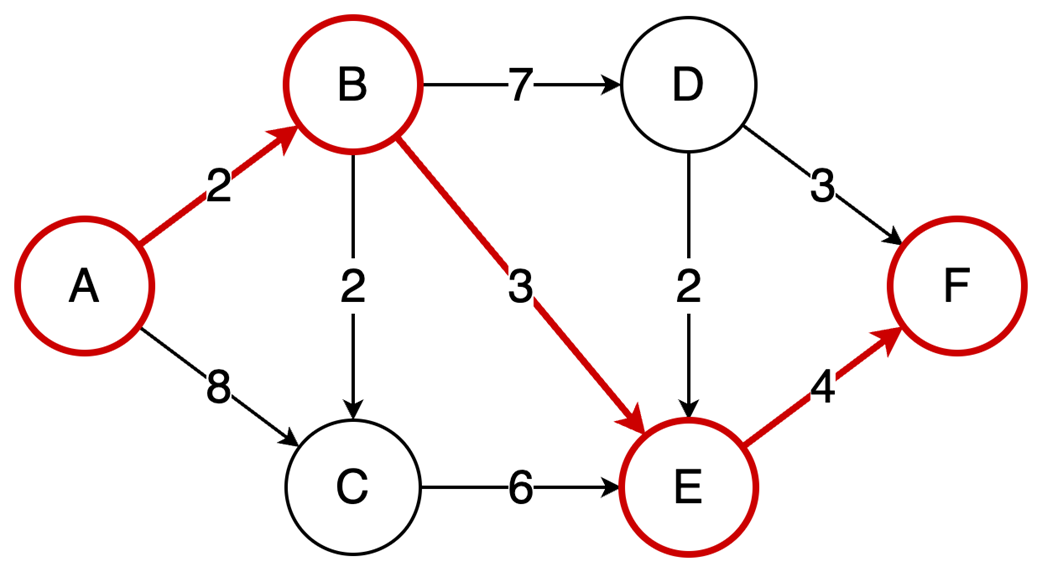

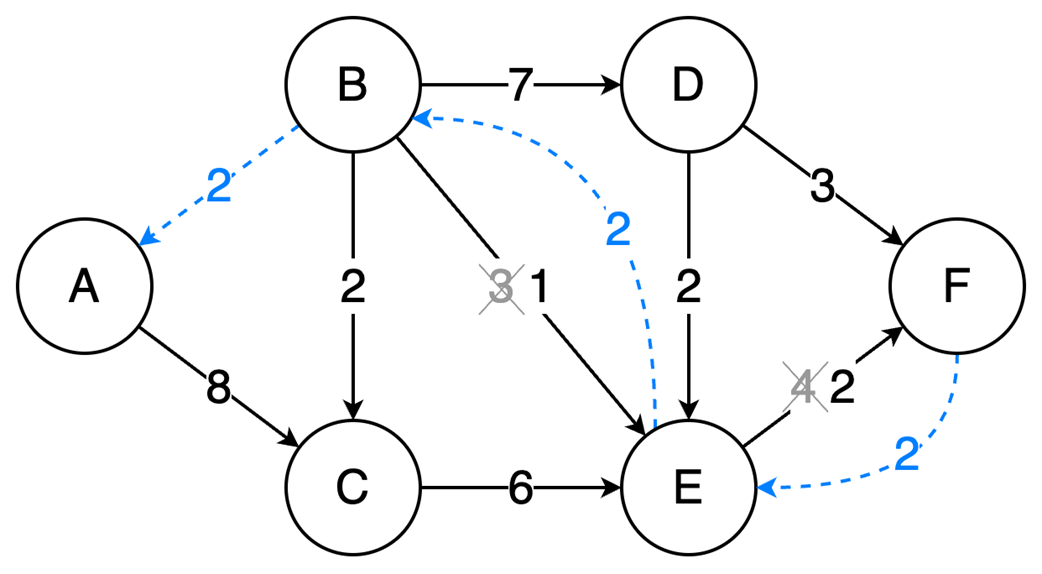

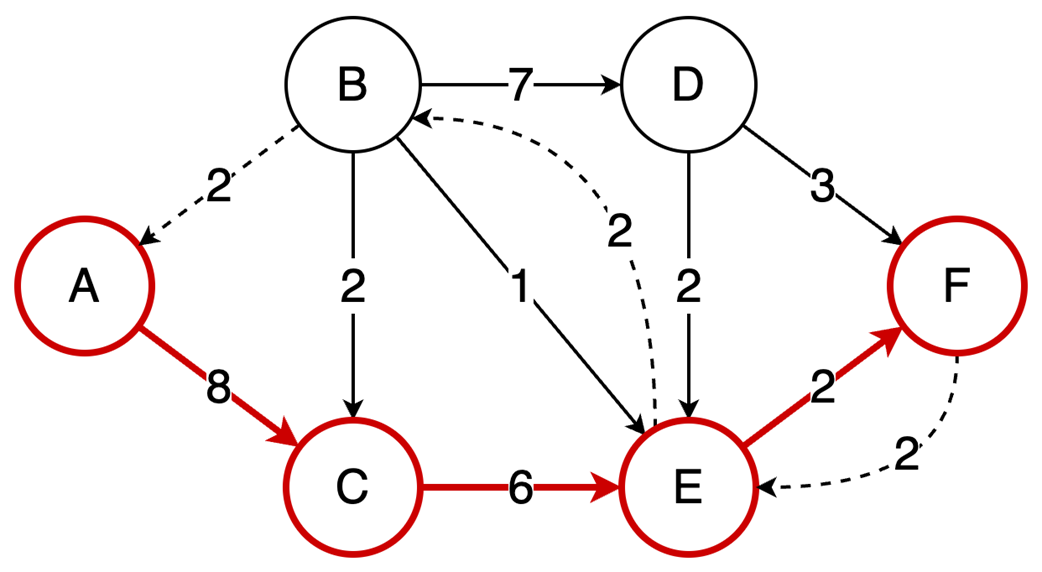

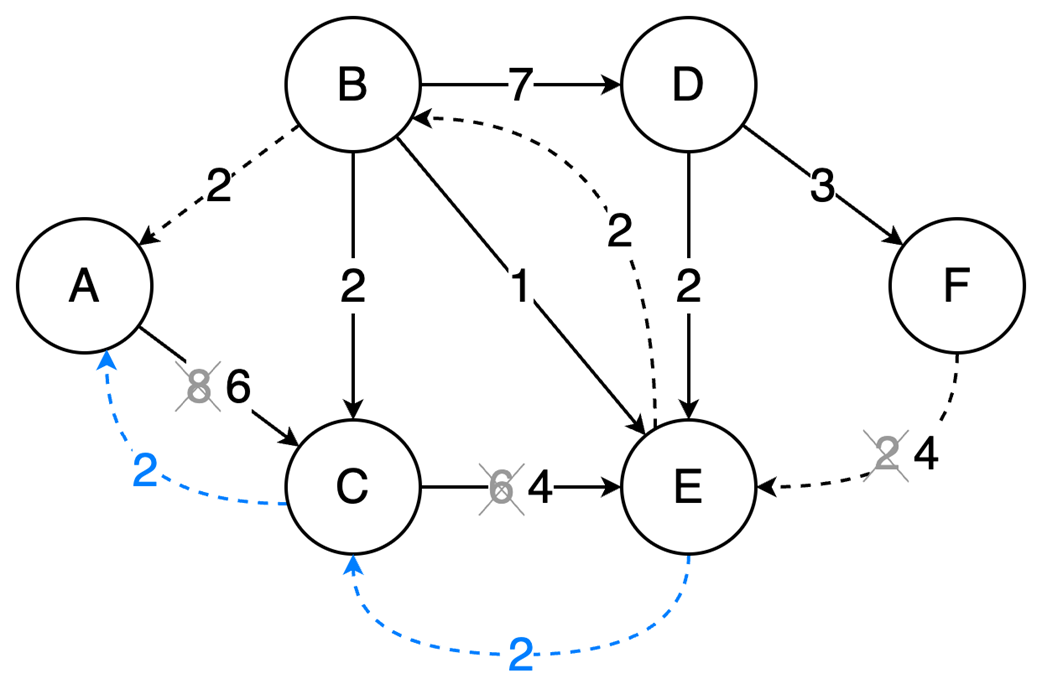

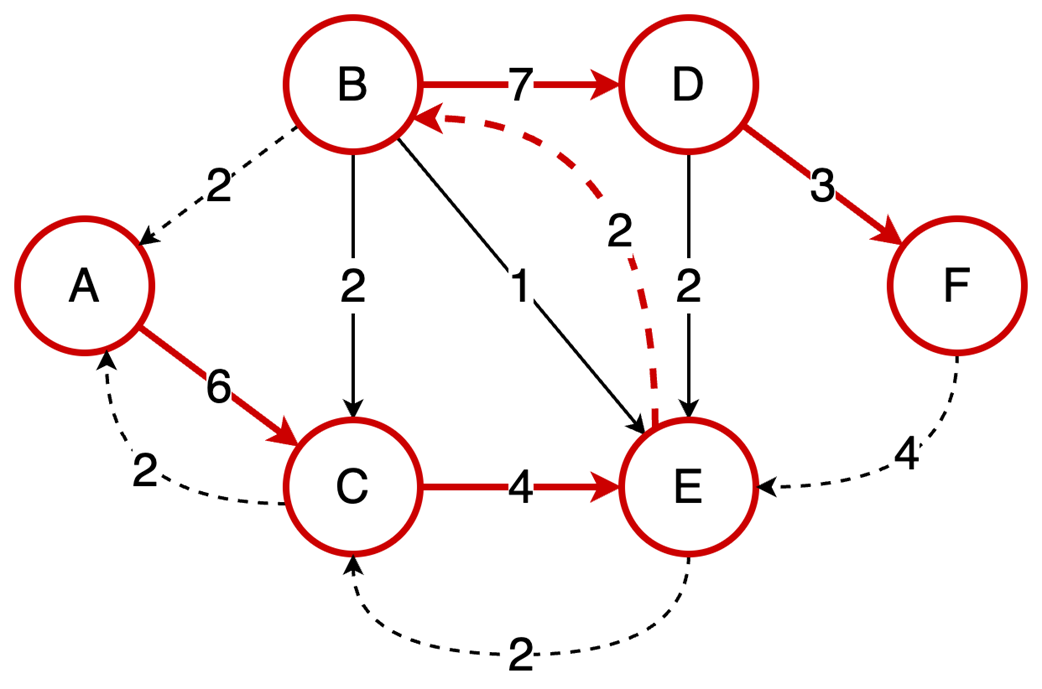

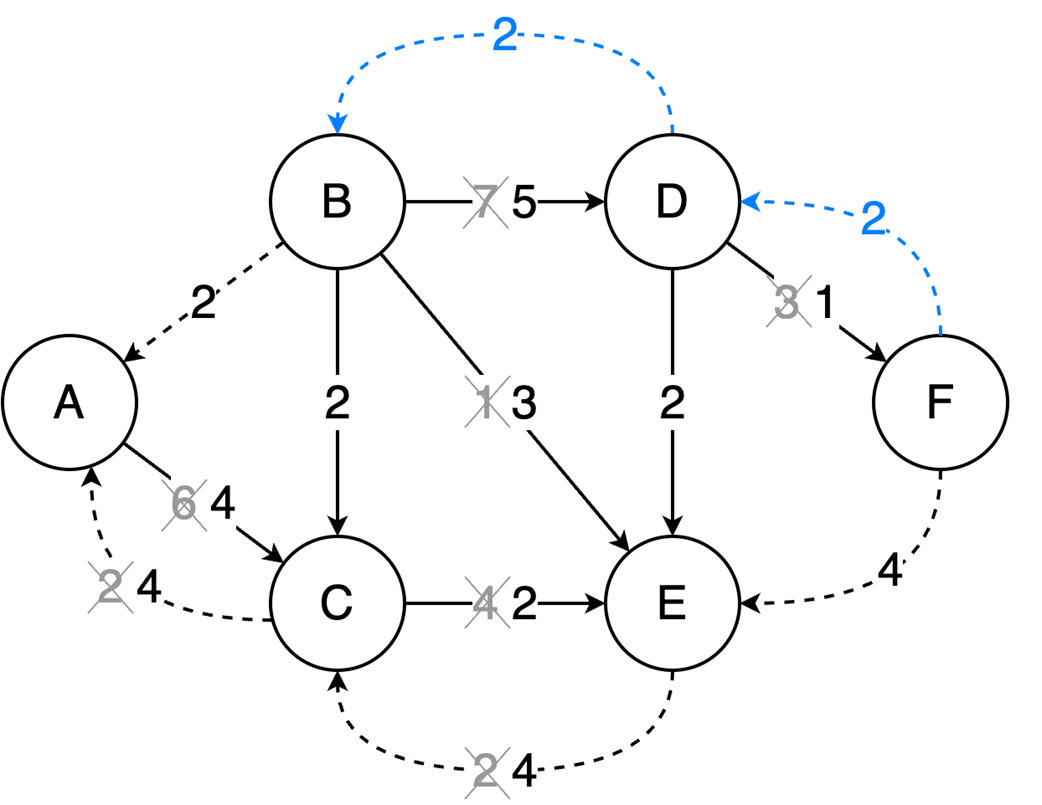

Next, the chapter surveys graphs—nodes and edges modeling relationships—along with key characteristics (directed/undirected, cyclic/acyclic, weighted/unweighted, connected/disconnected) and two primary representations: adjacency matrices (O(1) edge checks, O(v²) space) and adjacency lists (O(v+e) space, edge lookup proportional to degree). It outlines important algorithms: BFS for shortest paths in unweighted graphs, Floyd–Warshall for all-pairs shortest paths, and topological sort (in-degree counting with a queue) for ordering tasks in DAGs in O(v+e). Finally, it explains the Ford–Fulkerson method for maximum flow via repeated augmenting paths and residual networks with backward edges that permit flow redistribution, noting complexity O(EU) with arbitrary path selection and the Edmonds–Karp specialization (using BFS) that achieves O(VE²).

Summary

- Ford-Fulkerson repeatedly finds augmenting paths and pushes flow through them.

- Backward edges allow redistribution of flow, which corrects any suboptimal choices made by selecting arbitrary augmenting paths.

- The algorithm terminates when no more augmenting paths exist.

- Using DFS, the time complexity is O(EU), which depends on the final solution, but switching to BFS (Edmonds-Karp variation) results in a time complexity of O(VE²), making it dependent only on the graph structure.

- Arrays vs. linked lists: Pick for access vs. insertion/deletion patterns; mind cache locality.

- Heaps provide O(1) peek min/max and O(log n) updates; great for priority queues.

- Graphs model relationships; Choose representations (matrix/list) based on sparsity.

- Topological sort orders DAGs by dependencies in O(V+E).

- Ford‑Fulkerson finds max flow by augmenting paths and residual/backward edges.

FAQ

What are the main differences between arrays and linked lists?

- Memory layout: Arrays are contiguous in memory; linked lists are not guaranteed to be.

- Access time: Arrays provide O(1) index access; linked lists require O(n) traversal (unless you already have a node reference).

- Flexibility: Fixed-size arrays cannot grow; dynamic arrays and linked lists can grow/shrink.

- Overhead: Linked lists store pointers (references) per node, adding memory overhead.

How do fixed-size and dynamic arrays differ when inserting elements?

- Fixed-size arrays: Inserting beyond capacity requires allocating a new array and copying elements (O(n)).

- Dynamic arrays (e.g., Java ArrayList, C++ std::vector, Go slices): Amortized O(1) inserts thanks to extra capacity, but O(n) in worst-case when resizing occurs.

Why can linked lists be slower than arrays in practice, even for iteration?

- Lack of spatial locality leads to more CPU cache misses.

- SIMD-friendly iteration patterns are harder with lists.

- Even when nodes end up contiguous, iteration often has more cycles per step and less predictable access, reducing effective prefetching—observed to be significantly slower in practice.

When should I choose a linked list over an array?

- When you need frequent insertions/deletions not at the end and you have references to the positions (O(1) per change).

- Be mindful of pointer overhead and cache behavior; benchmark if performance is critical.

What is a binary heap and when should I use one?

A binary heap is a complete binary tree that enforces a heap property: in a min-heap, each parent ≤ its children; in a max-heap, each parent ≥ its children. It provides fast access to the minimum or the maximum (not both simultaneously). Typical use: implementing priority queues and algorithms like Dijkstra’s and heapsort.How is a binary heap stored in an array, and how do I find parents and children?

Heaps are commonly backed by arrays. For an element at index i: left child at 2i + 1, right child at 2i + 2, parent at (i − 1) / 2.What are the time complexities of common heap operations?

- insert: O(log n) via heapify up

- getMin/getMax: O(1)

- extractMin/extractMax: O(log n) via heapify down

- Build heap from an array: O(n) using heapify down (better than inserting one by one)

Adjacency matrix vs. adjacency list: which graph representation should I use?

- Adjacency matrix: O(1) edge lookup; O(v²) space (wastes space for undirected or sparse graphs). Best for dense graphs or constant-time membership checks.

- Adjacency list: O(d) edge lookup (d = vertex degree); O(v + e) space. Best for sparse graphs.

The Coder Cafe ebook for free

The Coder Cafe ebook for free