1 Introduction to Search and Optimization

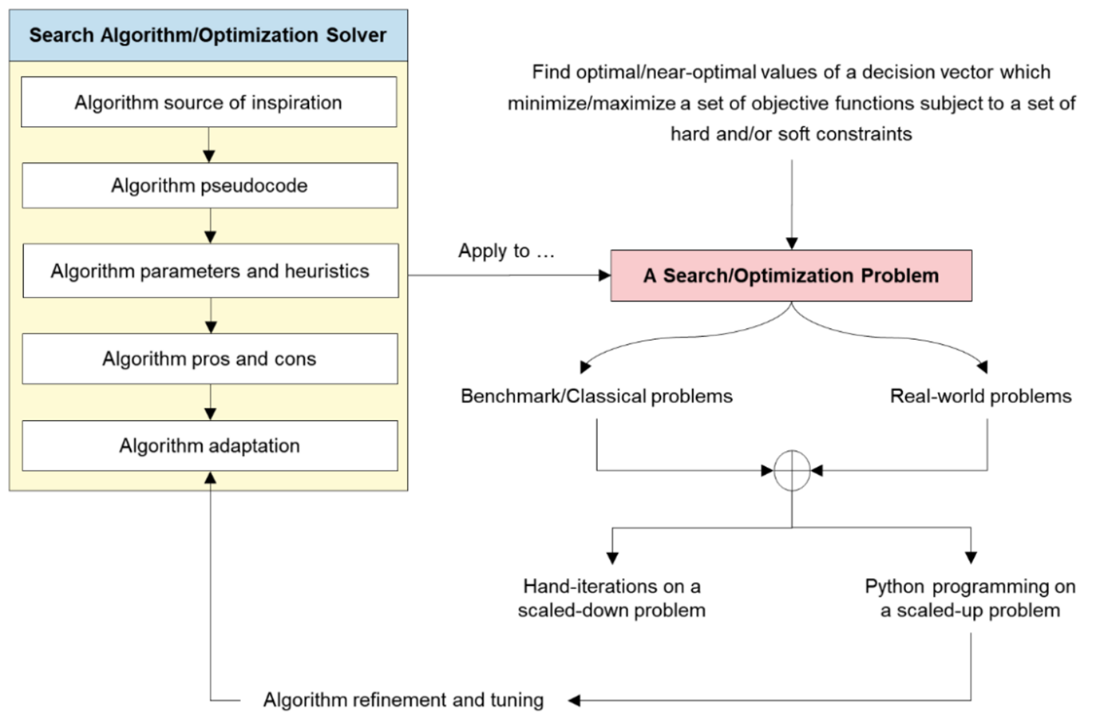

This chapter introduces search and optimization as pervasive ideas that shape behaviors in nature, decisions in daily life, and operations across industries. It positions “search” as the systematic traversal of states and “optimization” as the pursuit of optimal or near‑optimal solutions within feasible constraints, while cautioning that the payoff of sophisticated methods depends on problem scale and implementation costs. To build practical skill, the book moves from small, hand-solvable “toy” problems to real datasets and Python implementations, emphasizing tuning, performance, and scalability. It also distinguishes solution time horizons—design (slow, quality-focused), planning (seconds to minutes), and control (milliseconds to seconds)—highlighting when optimality must be traded for speed.

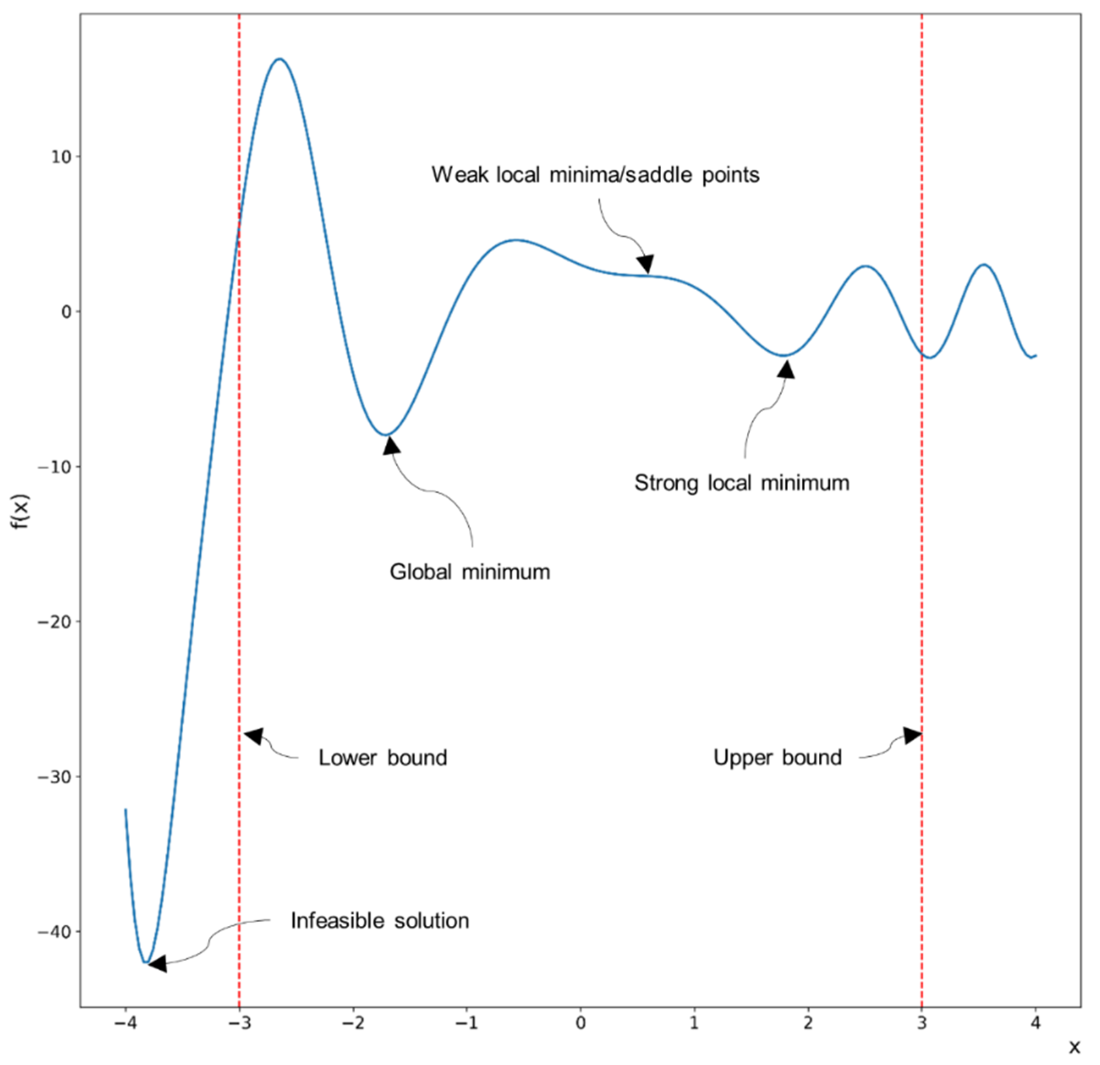

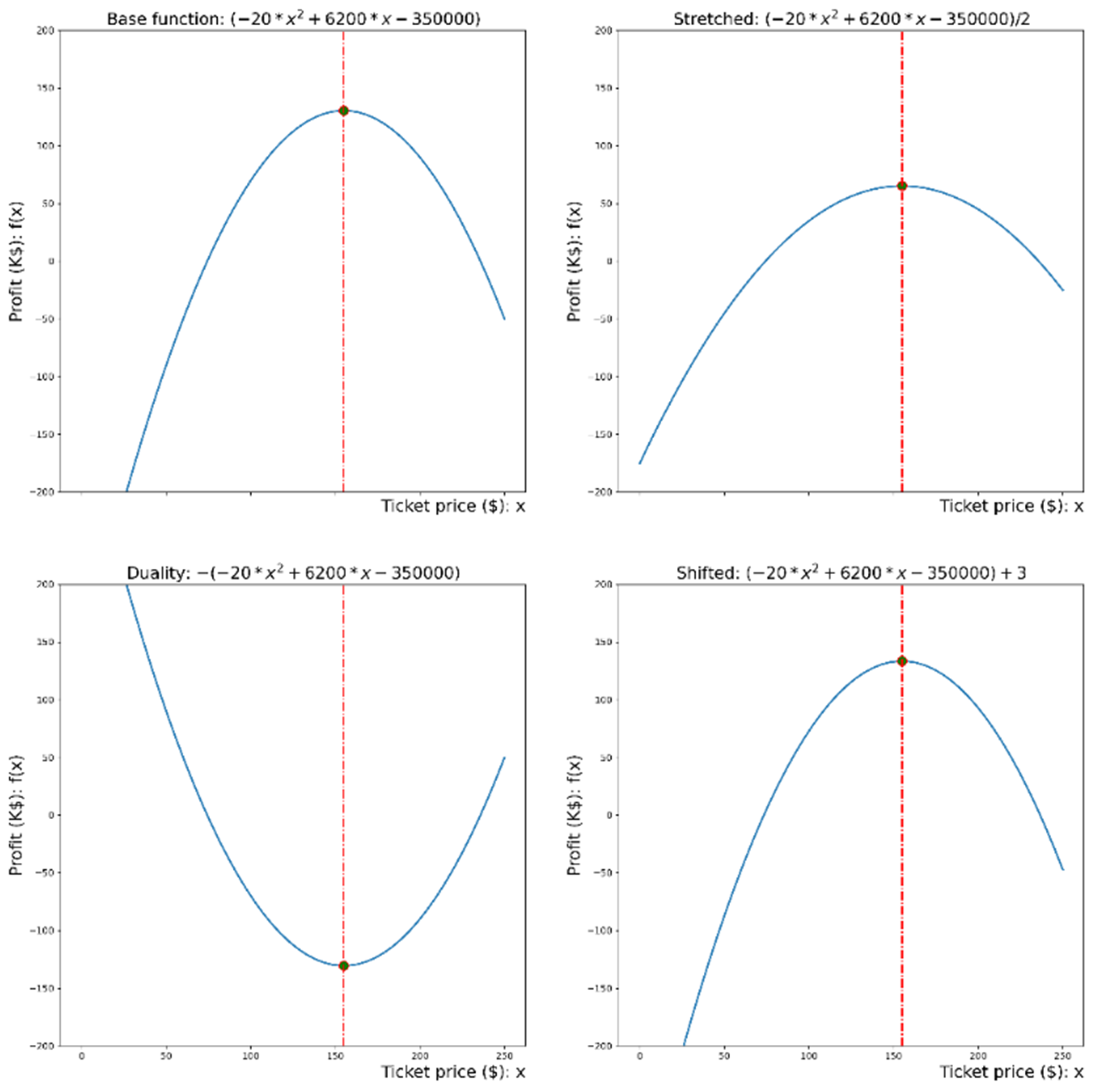

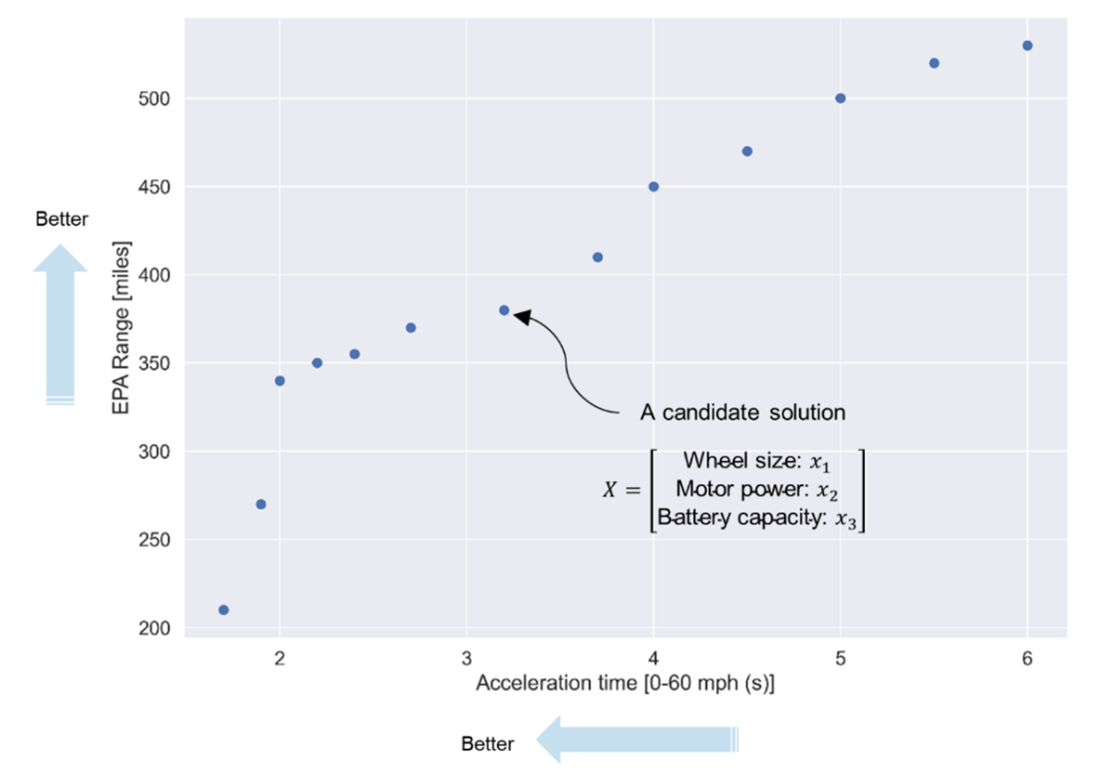

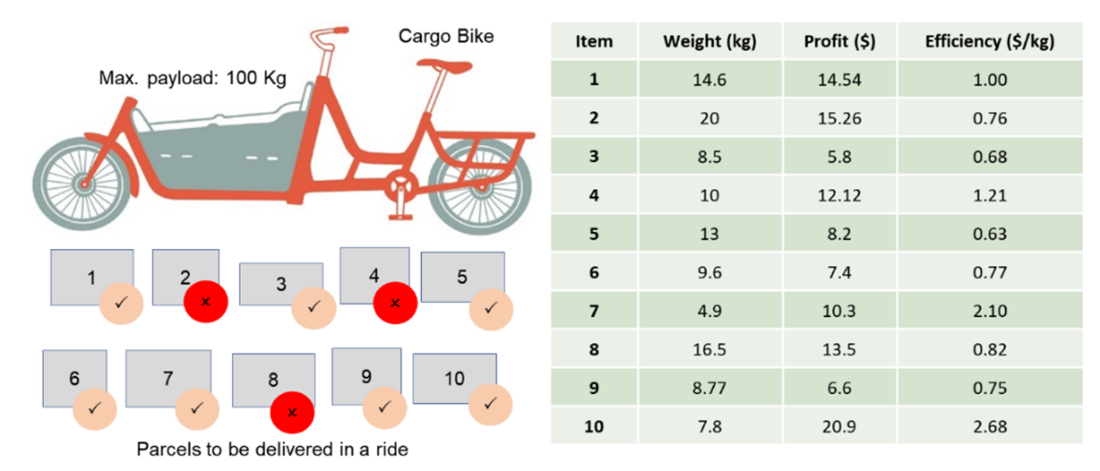

The chapter formalizes optimization problems via decision variables, objective functions, and constraints, clarifying feasible, optimal, and near‑optimal solutions and the presence of global and local optima in complex landscapes. It discusses duality and simple transformations that preserve the optimizer, contrasts single- with multi-objective problems, and outlines preference weighting versus Pareto approaches for navigating trade-offs. Constraint-satisfaction problems are presented as cases without an explicit objective, while hard versus soft constraints are modeled with penalties that can be made adaptive over time to balance feasibility and solution quality.

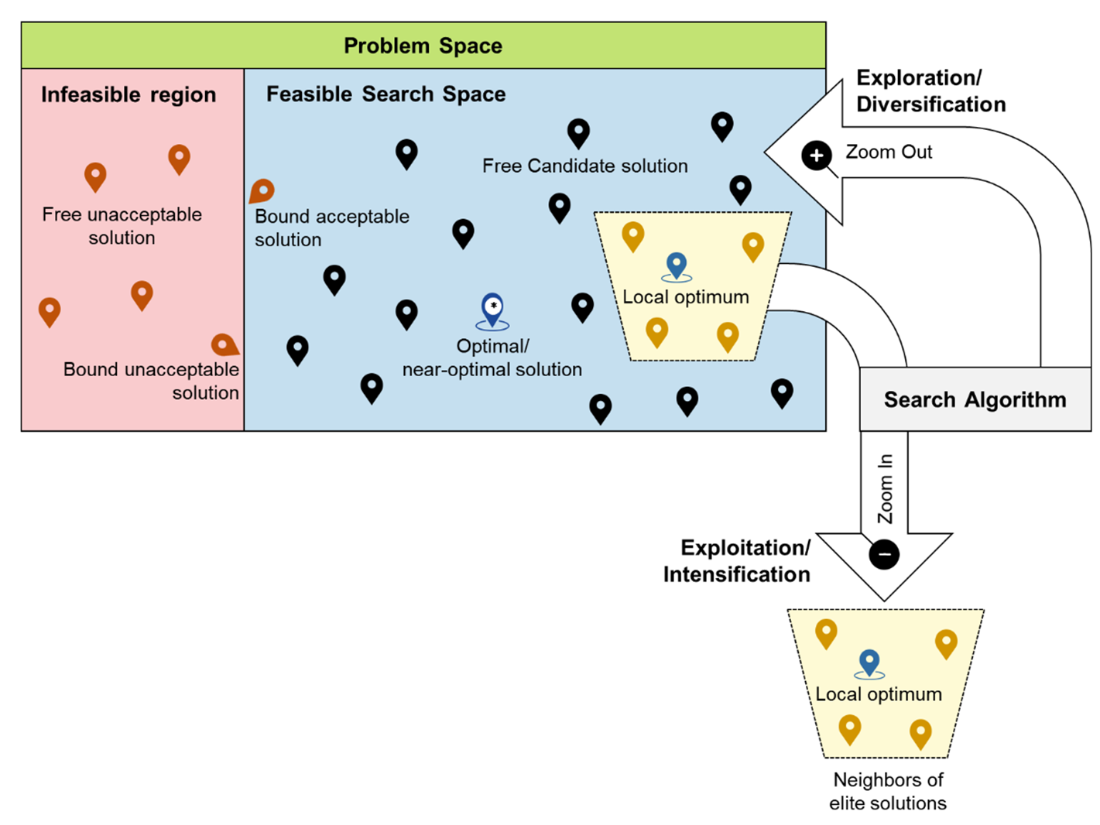

Problem structure is then contrasted between well-structured problems—where states, operators, and evaluation criteria are clear and computation is tractable—and ill-structured problems, which feature dynamics, uncertainty, partial observability, and combinatorial explosion. Examples illustrate both ends of the spectrum, including tasks that are theoretically well-posed but practically intractable at real-world scales. Given this landscape, the book emphasizes derivative-free, stochastic, black-box solvers suited to noisy, nonconvex, and partially observable settings. It concludes by framing the central search dilemma—exploration versus exploitation—showing how diversification helps escape local optima while intensification accelerates convergence, and why effective algorithms balance both to deliver high-quality solutions within realistic time budgets.

Book methodology. Each algorithm will be introduced following a structure that goes from explanation to application.

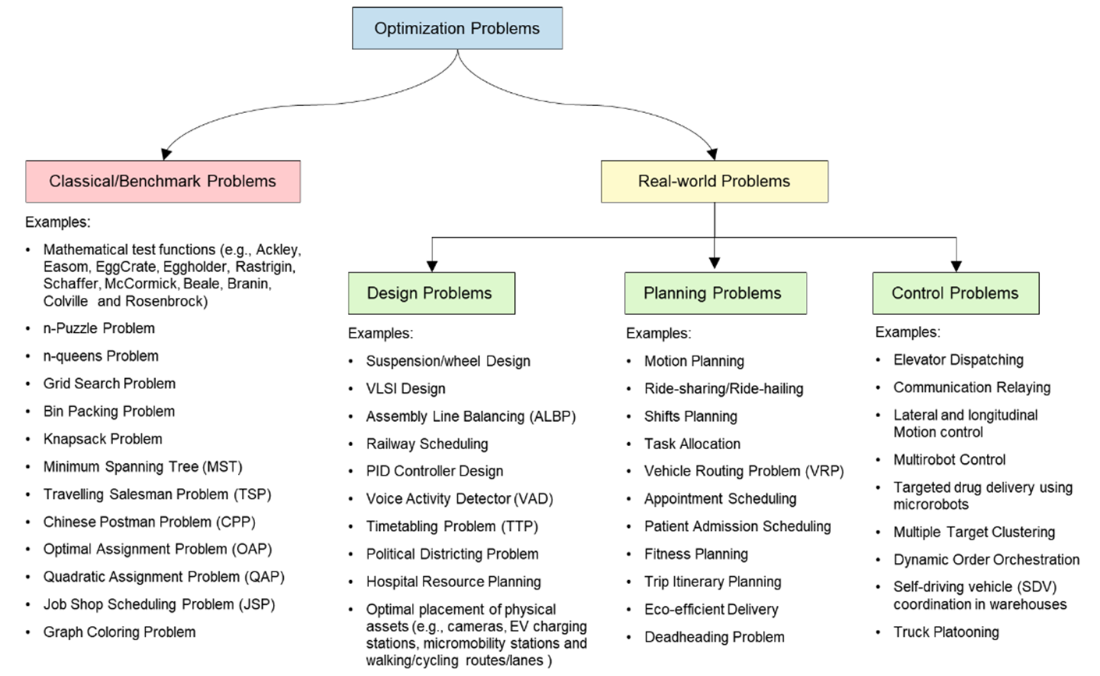

Examples of classical optimization and real-world optimization problems.

Feasible/acceptable solutions fall within the constraints of the problem. Feasible search space may display a combination of global, strong local, and weak local minima.

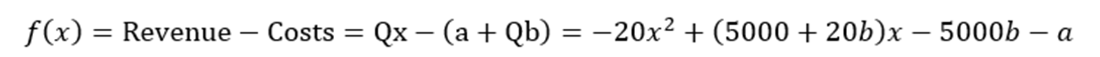

Equation 1.4

Duality principle and mathematical operations on an optimization problem.

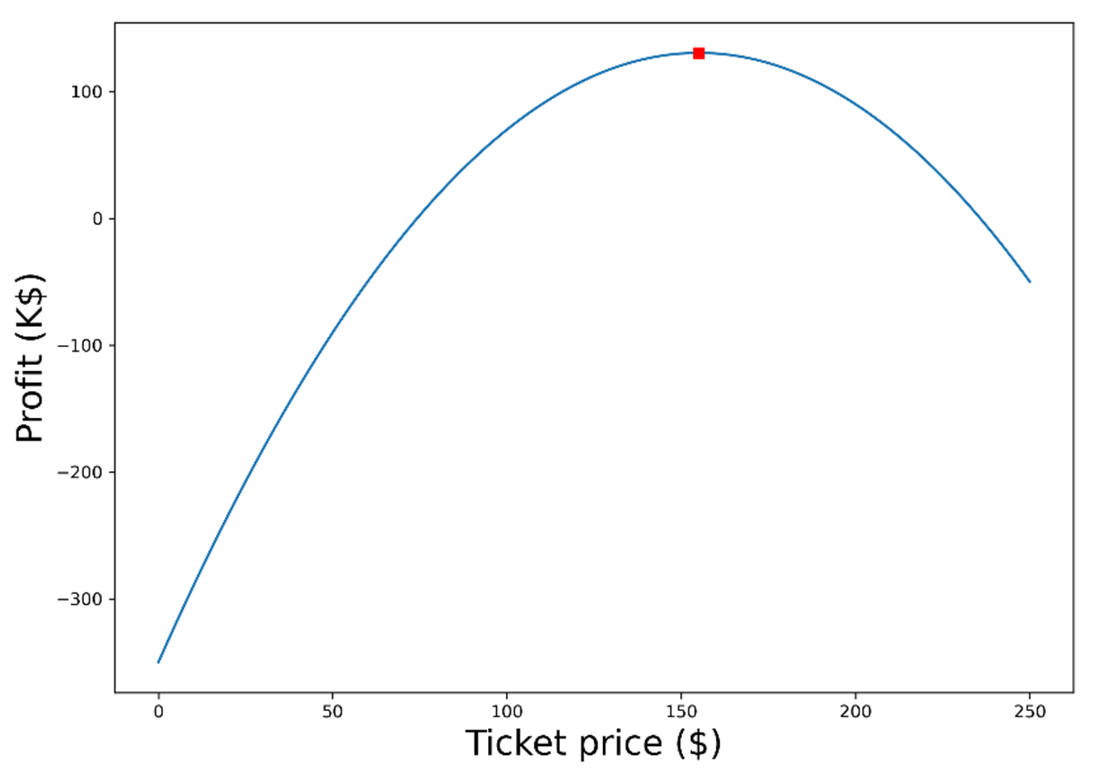

Ticket pricing problem. The optimal pricing which maximizes profits is $155 per ticket.

Electric vehicle design problem for maximizing EPA range and minimizing acceleration time.

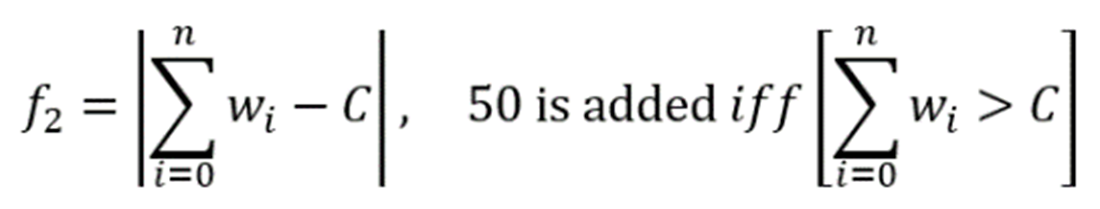

The cargo bike loading problem is an example of a problem with a soft constraint. While the weight of the packages can exceed the bike’s capacity, a penalty will be applied when the bike is overweight.

Equation 1.5

Equation 1.6

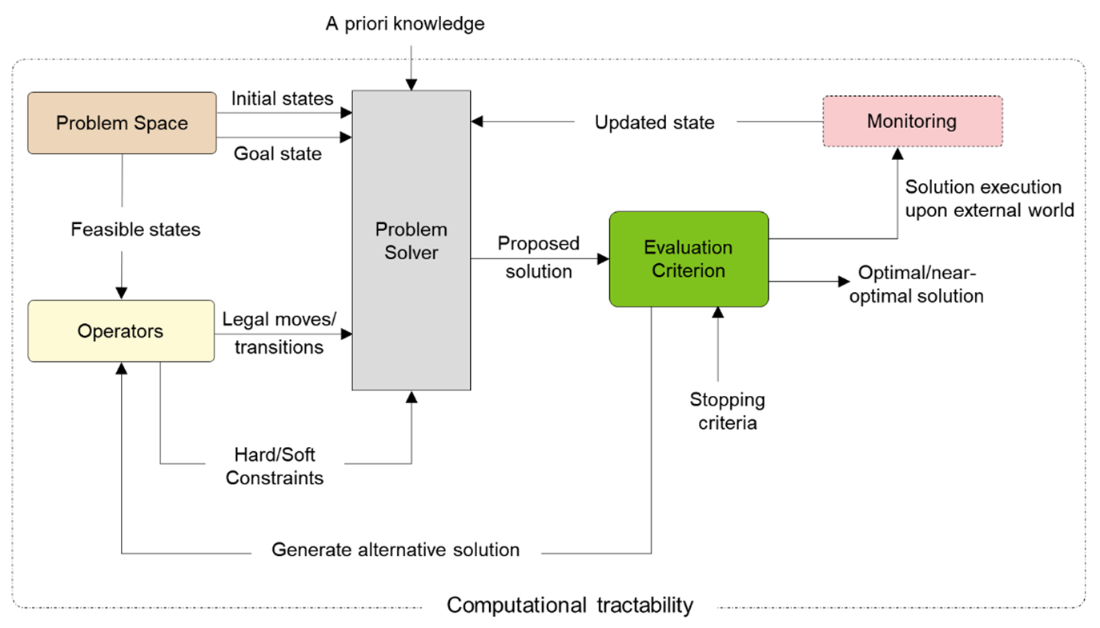

A well-structured problem will have a defined problem space, operators, and evaluation criteria.

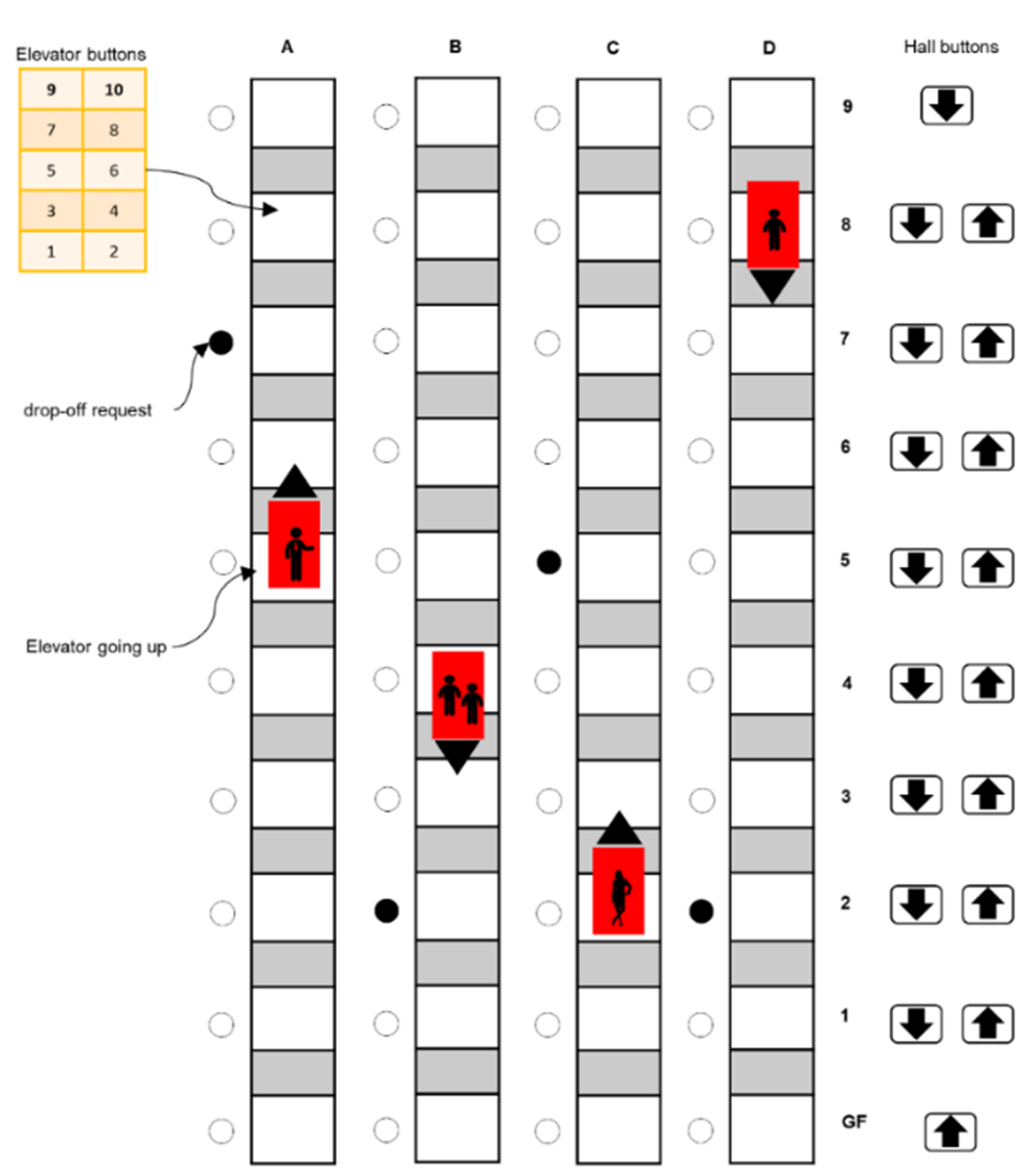

Elevator dispatching problem. With four elevator cars and ten floors, this problem has ~1021 possible states.

Search Dilemma. There is always a tradeoff between branching out to new areas of the search space or focusing on an area with known “good” or elite solutions.

Summary

- Optimization is ubiquitous and pervasive in numerous areas of life, industry, and research.

- Decision variables, objective functions and constraints are the main ingredients of optimization problems. Decision variables are the inputs that you have control over and that affect the objective function's value. Objective function is the function that needs to be optimized, either minimized or maximized. Constraints are the limitations or restrictions that the solution must satisfy.

- Optimization is a search process for finding the “best” solutions to a problem that provide the best objective function values, possibly subject to a given set of hard (must be satisfied) and soft (desirable to satisfy) constraints.

- Ill-structured problems are complex, discrete, or continuous problems without exact mathematical models and/or algorithmic solutions or general problem solvers. They usually have dynamic and/or partially observable large search spaces that cannot be handled by classical optimization methods.

- In many real-life applications, quickly finding a near-optimal solution is better than spending a large amount of time in search for an optimal solution.

- Two key concepts you’ll see frequently in future chapters are exploration/diversification and exploitation/intensification. Handling this search dilemma by achieving a trade-off between exploration and exploitation will allow the algorithm to find optimal or near-optimal solutions without getting trapped in local optima in an attractive region of the search space and without spending large amount of time.

Optimization Algorithms ebook for free

Optimization Algorithms ebook for free