1 Recommender systems in action

This chapter introduces recommender systems as the invisible infrastructure that orders an overwhelming digital world, explaining how algorithms rank items to surface what seems most relevant. It shows that recommendations and user behavior are bound in a tight feedback loop: what we see shapes what we click, and those clicks train what we see next. While this machinery brings convenience across domains—from shopping and travel to news, entertainment, and dating—it also concentrates attention, creating winners and losers, and can gradually steer preferences. The chapter frames this steering as algorithmic amplification: the way ranking and delivery choices magnify some content and voices over others, influencing culture, knowledge, and public discourse.

Social media is presented as the clearest arena where amplification plays out. Platforms evolved from chronological, subscription-based feeds to engagement-optimized, algorithmic timelines that inject out-of-network content and encourage passive consumption through infinite scroll and autoplay. As ranking targets engagement, virality and emotionally charged material travel farther, driving surveillance-driven business incentives while reshaping what users encounter and believe. The same dynamics have enabled grassroots mobilization and real-time reporting, yet also fueled mis- and disinformation, polarization, and pathways to radicalization. Creators adapt to opaque systems that can threaten livelihoods with small tweaks, users chase intermittent rewards that foster compulsive use, and vulnerable populations risk being funneled toward harmful content, illustrating how curation and ranking together function as de facto editorial power.

Because attention is finite and the systems are opaque, the chapter argues for assessing societal impact through the lens of amplification while acknowledging the difficulty: there is no agreed-upon notion of value, engagement is an imperfect proxy, popularity snowballs, and user–algorithm coevolution blurs causality over time. The stakes are amplified by platform dominance, network effects, and limited regulation, leaving a few private actors with supra-national influence over information flows. The authors propose treating amplification metrics like evolving “nutrition labels” for platforms, reported with methodological transparency and scoped at population level, and caution that accountability must consider both stages—what content is selected and how it is ranked—without anthropomorphizing algorithms that simply execute designers’ objectives.

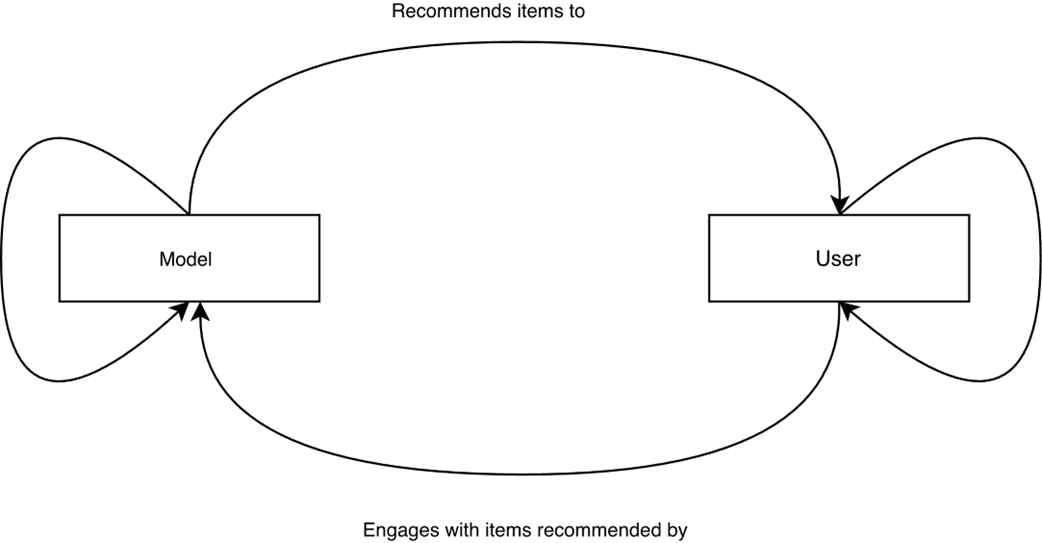

The feedback loop between user and recommender systems. Users and recommender systems are in a mutual feedback loop, with the output of one serving as the input to the other. The output of the algorithm, the recommendations, is the input for the users. The users’ output, what they engage with, is a signal for the recommender. On top of that, both the user and the recommender system update their internal state. Users change their minds and evolve their preferences over time, while algorithms learn users’ preferences and try to align more with them.

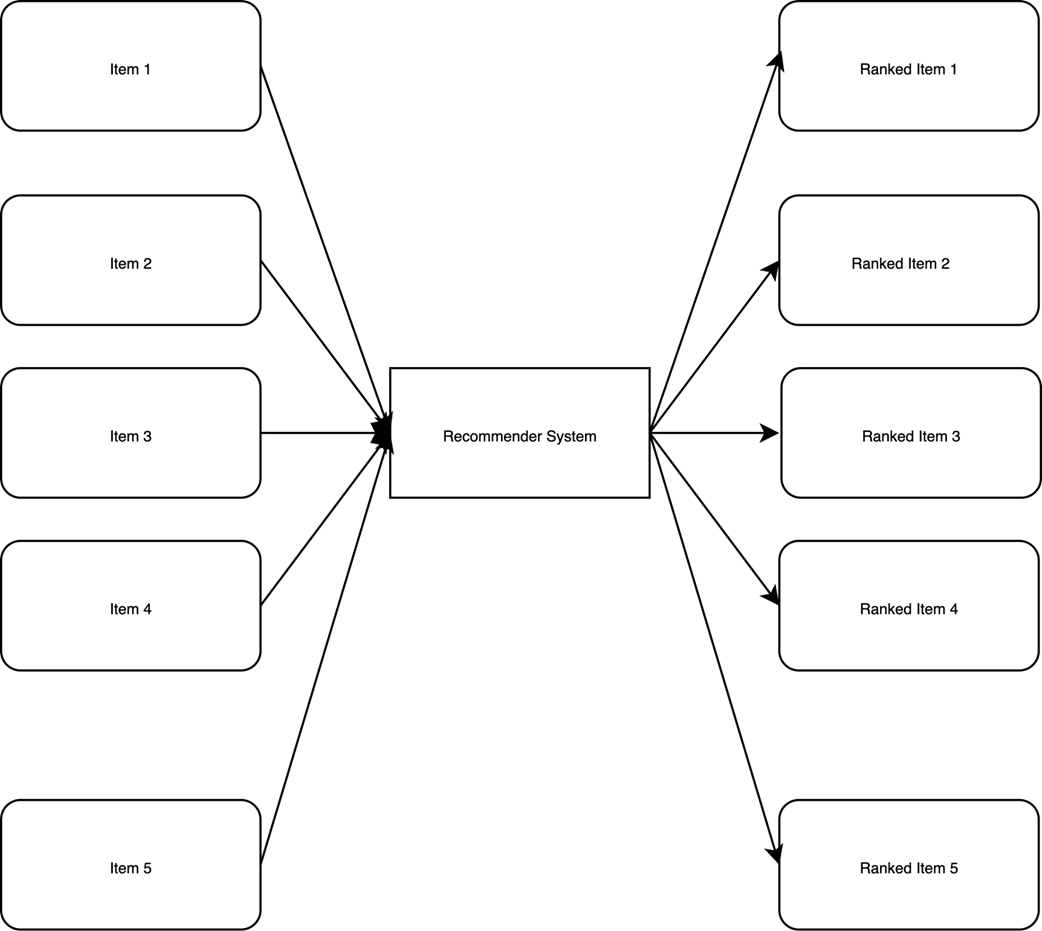

Given a list of items, this recommender system reranks them according to a predefined metric, such as value to the user.

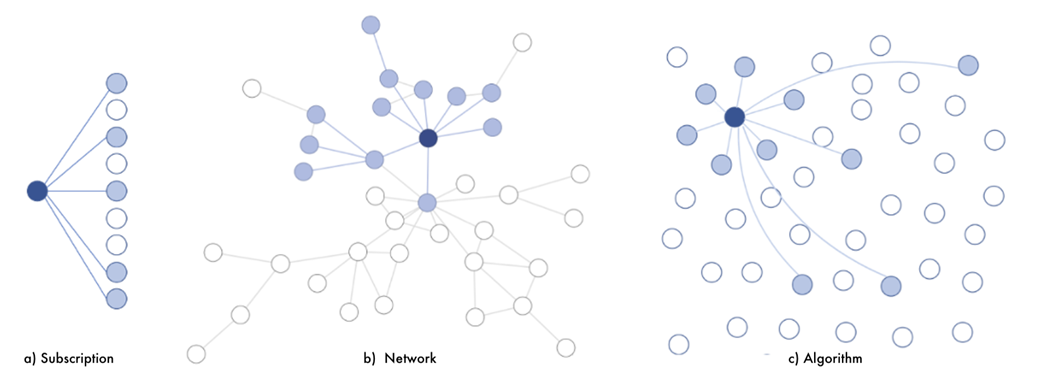

Various social media models. In the Subscription model, the content is seen only by users who explicitly follow the content producer, with no options or resharing. In the Network model, users can also reshare content from users they follow, enabling the distribution of content outside of the immediate network. Finally, in the Algorithmic model, an algorithm can add content to users’ feeds, even with no direct connection to the content itself or its author.

Summary

- Recommender systems are a powerful tool—and often underappreciated as a tool to order vast amounts of information for us. As a technology that pervades every application we interact with, RecSys have the power to influence our preferences in numerous domains, including highly consequential ones such as news consumption, dating choices, and financial decisions.

- Social media was created as a tool to connect people on the internet—at first free of commercial interest—and to build location-free communities around shared interests.

- The evolution of the internet has brought about more online platforms that have been able to connect an unprecedented number of people. Given the high running costs and the investors’ demands, platforms were nudged into finding ways of monetizing such efforts.

- Social media platforms began experimenting with recommender systems as a means to align business and customer interests. By explicitly indicating business goals and taking into account users’ behavior, platforms were able to serve more relevant content to users—which made the users be more active and spend more time on the platforms.

- The use of such algorithms raises important questions about algorithmic amplification, such as understanding which content is amplified more and why. Different types of platform designs enable various approaches to thinking about amplification.

Hidden Influences ebook for free

Hidden Influences ebook for free