1 Introduction to functional programming

This opening chapter introduces the functional programming mindset in the context of modern C++, contrasting imperative “how to do it” code with declarative “what to achieve” expressions. It frames functions as primary building blocks and emphasizes expressing intent through composition and higher-level abstractions rather than managing stepwise control flow and state. Through simple examples (like counting lines across files), it shows the progression from manual loops to standard algorithms and finally to range-based pipelines, illustrating how functional idioms make code shorter, clearer, and closer to the problem statement while coexisting productively with object-oriented design in a multiparadigm language.

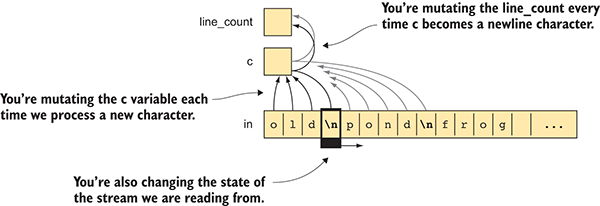

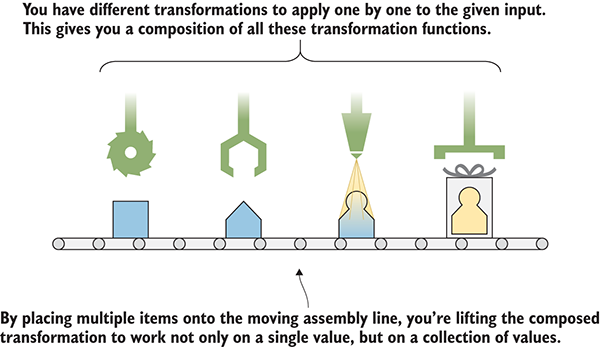

A central theme is purity: preferring functions without observable side effects and minimizing mutable state to reduce bugs and make reasoning easier. The chapter explains a pragmatic view of pure functions—those that appear side-effect-free to their callers—even when implementation details perform unavoidable mutations (e.g., I/O). Thinking functionally means decomposing problems into small, composable transformations and lifting single-item functions to operate over collections, much like stations on an assembly line. The benefits include brevity and readability, safer refactoring, easier parallelization (thanks to the absence of shared mutable state), and fewer opportunities for subtle defects.

The text also surveys C++’s evolution toward functional styles: templates enabling generic algorithms, passing function-like entities, and later features (such as auto and lambdas) that make higher-order programming practical and expressive. It advocates leaning on well-crafted library abstractions (STL algorithms and ranges) for both clarity and “continuous optimization” as compilers and libraries improve. Finally, it outlines what readers will learn: higher-order functions, immutable design strategies, ranges for composable dataflow, algebraic data types to constrain program states, and monadic patterns for building complex yet modular systems—skills that yield concise, maintainable, and scalable C++ code.

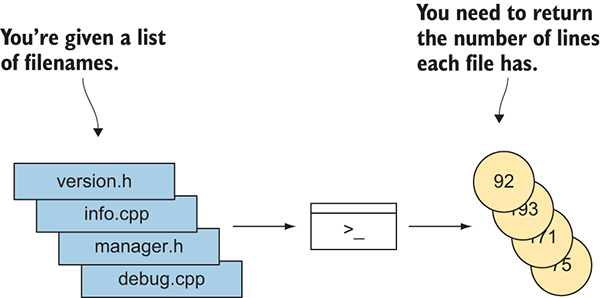

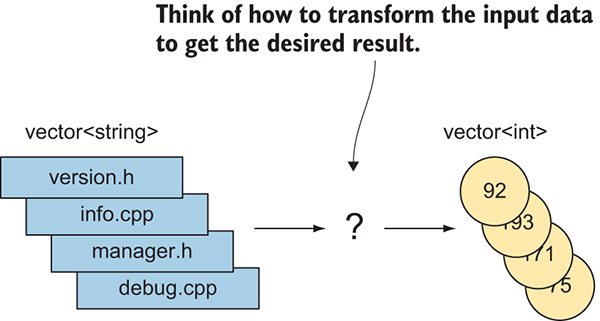

The program input is a list of files. The program needs to return the number of newlines in each file as its output.

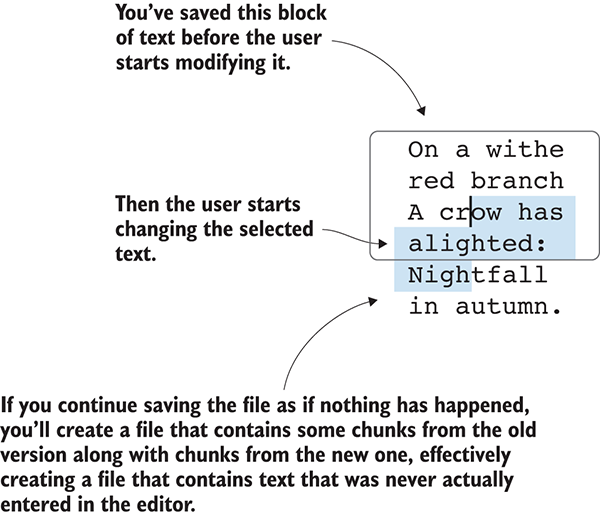

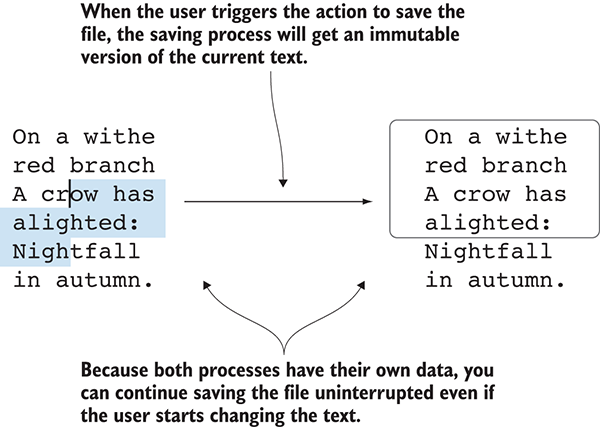

If you allow the user to modify the text while you’re saving it, incomplete or invalid data could be saved, thus creating a corrupted file.

If you either create a full copy or use a structure that can remember multiple versions of data at the same time, you can decouple the processes of saving the file and changing the text in the text editor.

This example needs to modify a couple of independent variables while counting the number of newlines in a single file. Some changes depend on each other, and others don’t.

When thinking functionally, you consider the transformations you need to apply to the given input to get the desired output as the result.

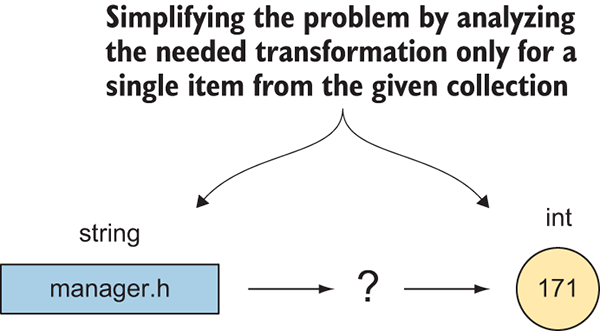

You can perform the same transformation on each element in a collection. This allows you to look at the simpler problem of transforming a single item instead of a collection of items.

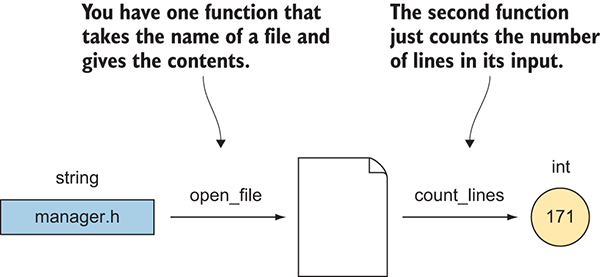

You can decompose a bigger problem of counting the number of lines in a file whose name you have into two smaller problems: opening a file, given its name; and counting the number of lines in a given file.

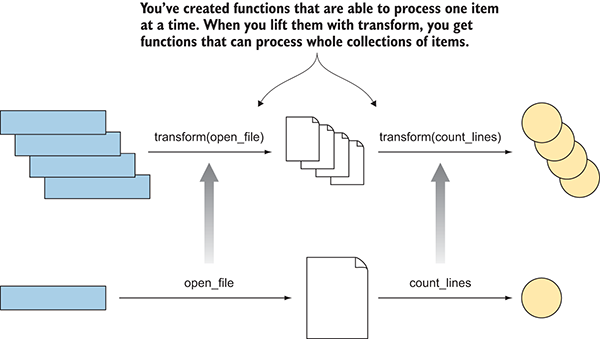

By using transform, you can create functions that can process collections of items from functions that can process only one item at a time.

Function composition and lifting can be compared to a moving assembly line. Different transformations work on single items. By lifting these transformations to work on collections of items and composing them so that the result of one transformation is passed on to the next transformation, you get an assembly line that applies a series of transformations to as many items as you want.

Summary

- The main philosophy of functional programming is that you shouldn’t concern yourself with the way something should work, but rather with what it should do.

- Both approaches—functional programming and object-oriented programming—have a lot to offer. You should know when to use one, when to use the other, and when to combine them.

- C++ is a multiparadigm programming language you can use to write programs in various styles—procedural, object-oriented, and functional—and combine those styles with generic programming.

- Functional programming goes hand-in-hand with generic programming, especially in C++. They both inspire programmers not to think at the hardware level, but to move higher.

- Function lifting lets you create functions that operate on collections of values from functions that operate only on single values. With function composition, you can pass a value through a chain of transformations, and each transformation passes its result to the next.

- Avoiding mutable state improves the correctness of code and removes the need for mutexes in multithreaded code.

- Thinking functionally means thinking about the input data and the transformations you need to perform to get the desired output.

Functional Programming in C++ ebook for free

Functional Programming in C++ ebook for free